Royce Kurmelovs

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).

To talk about Geoff Goodfellow’s work with any insight, it is first necessary to put it into the proper context. Though the stories he tells and the characters he has captured over his long career may well be familiar to many, the eminent poet of everyday life is often misunderstood.

Goodfellow first swapped the construction business for poetry in 1982 after hurt his back in a workplace injury. As he began to write, his work came to belong to a strand of Australian – and uniquely South Australian – social realism that is arguably under-appreciated. His subjects were not glamorous or important people, but those who were otherwise ordinary who were leading messy lives. His technique was to record the slang, the intonation, the dress, the circumstances, the screw ups and the dreams of his subjects.

As an approach, it has largely meant his work has endured. In rendering people as they are, without fear or favour, people who wouldn’t ordinarily see themselves in print find their own stories told. In this way his work has served as an important record of working class and South Australian stories.

This quality is what makes his work read more like a photograph and his poetry more akin to journalism – though it would be a mistake to think they are purely an exercise in description. Few, if any, of the characters he presents are perfect people – and that is arguably the point. All are constrained by their abilities, their resources, or their circumstances. Some, when given the opportunity, are noble. Others are not. A select few are cruel. Though this may be confronting, readers with a critical eye will recognise the question being asked of them: what made these people that way? The answer to this is implied: we did. Each day there are whole words we chose to ignore and so we are complicit in their creation.

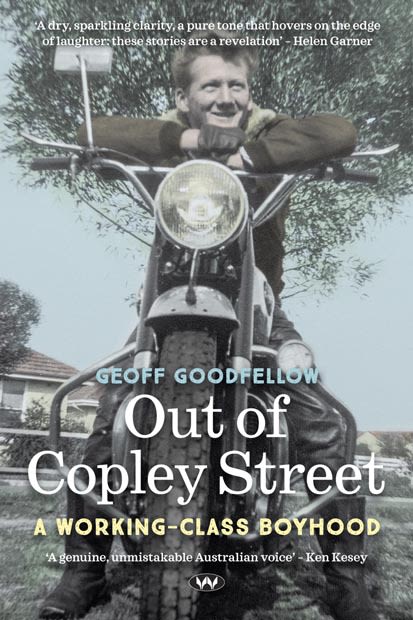

Understanding this about Goodfellow’s back catalogue is necessary to grasp what makes Out of Copley Street unique. As a book, it has been published at a time when contemporaries like Helen Garner have been publishing her diaries. As memoir, Goodfellow’s book marks a departure from poetry into prose. It begins by framing itself as a series of recollections from a man thinking about death – in this case the death of American novelist Ken Kesey, a personal friend. Though it is rendered in a conversational style, the work relies on the same techniques that characterise his poetry. There is the usual feel for rhythm, an ear for the vernacular and an eye for the deeper significance in simple interactions.

What is markedly different in this work is the tone and temperament. Here the central figure isn’t the hard man who once shut down building sites to read poetry to construction workers, but a more reflective voice talking as if in conversation with a friend over dinner. The vignettes track its author through his early boyhood to his teenage years. If the subjects are work, trauma and coming to terms with the world, its general theme is discovery. We watch a young Geoff Goodfellow eagerly enter adulthood and begin to grapple with the realities of what is clearly a man’s world. Violence, in its various forms, is the language of the street but also a means to earn respect. The lessons taught then will take a lifetime to unlearn, as Goodfellow explains in the final chapter. On the job, everyone is on the make. Workers cheat their bosses even as their bosses exploit them, and everyone rips off the customer. Yet from an early age Goodfellow recognises the nobility in people. This is encapsulated by the figure of his father, a man who grapples with PTSD and its associated effects, but who is still capable of great feats of beauty, charisma and wisdom.

By its end we’re left with a remarkable self-portrait that offers new insight, especially for long-time fans. If his past work invites us to consider how the world made others, Out of Copley Street shows us how the world of Geoff Goodfellow’s childhood forged him.

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).