Trent Parke: The Black Rose

Trent Parke’s odyssey demands such a context to be understood and appreciated.

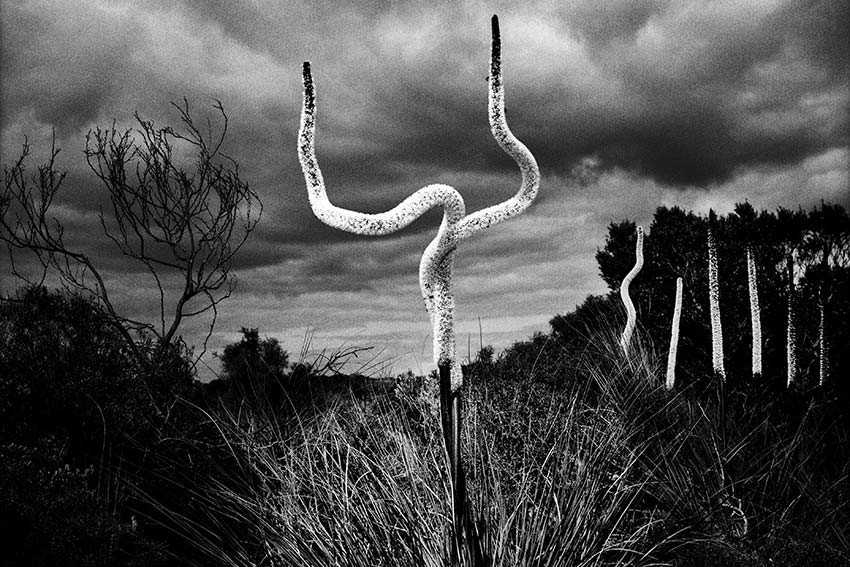

Zen Buddhists have a word for it – satori. A spontaneous awakening, comprehension or understanding. It’s the first step in a disciplined pathway towards enlightenment about the nature of things. Trent Parke’s odyssey demands such a context to be understood and appreciated. Myriad photographic images, large and small, that compose this epic exhibition project, unravel like a series of fragmentary moments and memories bursting into consciousness. They vary in scale and significance from sunsets to ants feasting on a biscuit. Some are composed and polished to great dramatic effect. Others are scraps, snapped on the run, nailing with a Blair Witch flashgun whatever happened to get in the way. There’s another context. Tim Winton. You know – the way that writer selects and strings his words and silences to give you the taste of salt, the grit of sand between the toes, the muffled boom of a wave on a distant reef, the thin sound of country seeping out of a doors-closed Toyota ute. Parke has this touch. So intense is the artist’s focus and intuitive his gaze that his images have the capacity to awaken corresponding feelings of life as a sometimes bewildering but at other times, strangely coherent a air. Don’t enter this exhibition looking for neatly arranged breadcrumb trails. There is no Way Back, Then This Happened and Look What’s Happening Now. It’s all about Now. All new work, produced in a very compact period of time. There were 14 books to start with, created by the artist as a means of pulling together the disparate threads of his studio work. A selection is included in the exhibition. They, and texts in the accompanying, richly illustrated catalogue, reveal Parke to be a writer of sparse prose which matches the ‘found object’ characteristics of his images. In negotiation with the two The Black Rose curators, Julie Robinson and Maria Zagala, clusters of images took shape and eventually defined the structure of the exhibition design. This is risky business but the rewards are evident in startling and unexpected conjunctions that give the exhibition a life of its own. In this sense it approaches a series of Duchampian Étant donnés voyeuristic double takes as ashes of reality hit the imagination.There is another context. A personal one. It tells of a kid growing up in Newcastle who eventually became a sports photographer and got to see the world in the company of ‘Warnie’, ‘Pidge’ and the gang. In 1999 he left this behind to work as a freelance photographer. Gone but not forsaken. Shooting sports action taught him to anticipate events and moments. As he describes it, “I can sense all the elements of a picture while they are still forming around me.” When not shooting sport he walked the streets of Sydney, looking for subjects and found them in the everyday of people working and hanging out. An extended, outback road trip in 2003-04 (“compelled into this country” like Patrick White’s Voss?) with photographic artist (now his wife) Narelle Autio, opened his eyes to natural and social worlds of difference and diversity. From this journey came a landmark exhibition, Minutes to Midnight in which Parke set out to “capture the moods and emotions of a still young Australia before it [was] significantly changed forever.” In composing this exhibition, the artist experimented with the scale and placement of images to manipulate their meaning. This strategy is evident in The Black Rose. Deeper into this context is the narrative of Trent Parke as a son and father. The sudden, tragic death of his mother (when he was 12 years old) cast him adrift from childhood. Now a father of two, the artist re-engages, in The Black Rose with childhood memory, loss and pain but also the great cycle of life and death in which small moments of absurdity, ironic humour and parental affection alleviate the omnipresence of destiny. So we are left in what contemporary cultural commentators call a ‘hovering state’ or derive (drift), in which precise meanings are redundant but the truth of dreams can bloom like a black rose on the midnight hour. Paul Valery once said that a man’s true secrets are more secret to himself than they are to others. One can only guess that this remarkable act of public disclosure holds as much magic, mystery and uncertainty for the artist as the viewer. Trent Parke, The Black Rose Art Gallery of South Australia The exhibition continues until Sunday, May 10 artgallery.sa.gov.au