Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl Review

As far as the members of US three-piece indie–punk outfit Sleater–Kinney knew, they would never reunite once they went on what they officially called a hiatus at the end of their 2006 tour.

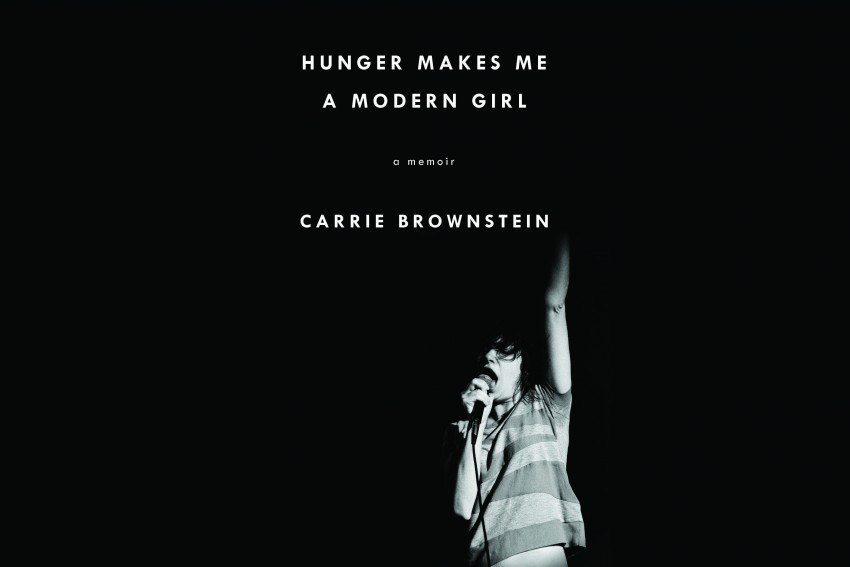

In her memoir, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl (a lyric from the band’s song Modern Girl), guitarist and singer Carrie Brownstein shoulders the blame for putting an end to the band.

Ahead of a show in Brussels, during the European leg of that last tour, worn–out, wracked with self–loathing and debilitated physically and emotionally by a bout of stress–driven shingles, Brownstein took to herself with her own fists.

Band mates Corin Tucker and Janet Weiss were horrified. It was the culmination of years of uncompromising dedication to the band and to its ideologies and ethics. Brownstein could no longer face being tied to the collective identity of the band that had been her home for more than a decade.

Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl traces the parts of Brownstein’s life that gave shape to the person that would become so utterly consumed by her band: her not–quite– right suburban childhood in Redmond, Washington, her move into the powerful feminist punk music community of Olympia where Sleater–Kinney was formed, through the writing and recording of their albums (satisfying the Sleater–Kinney completist’s needs), the difficulties and joys of touring, the need to continue resisting the everyday sexism of the music industry, the band’s collapse and the days of powerful grief that followed.

For an Australian reader, it’s something of a thrill to read an account (and see a photo) of Brownstein and Tucker’s first gig as Sleater–Kinney in Sydney, and the on–the–fly recording of their first album in then–drummer Laura MacFarlane’s Melbourne share house the night before Brownstein and Tucker flew out of the country.

Brownstein is at pains to emphasise how deeply unglamourous the life of the band was in those early days – a theme that continues through the book. The rock life for people who take their music as seriously as Brownstein and company is not lucrative.

If ever an artist from rock’s more uncompromising edge has become subsumed into the mainstream of culture, it is Carrie Brownstein. These days, more often than not, she is billed as one of the stars of the satirical sketch comedy series Portlandia, who also just happens to play in a rock band. (It’s no small coincidence that this book has appeared just as Sleater–Kinney have reformed and are touring to support their – very excellent – new album.)

Brownstein’s memoir is, at one level, a neat way to introduce those who are familiar with her from her not–quite–but–almost sunny, deadpan satirical comedy, to her musical ‘pre–history’. What’s most interesting is Brownstein’s willingness to approach herself and her music self–critically. Even in the midst of her account of belonging to and remaining in the Pacific Northwest music scene, she works though the problem of the tendency for scenes like this, whether musical, artistic or otherwise, to become as closed as the very cultures they are reacting against.

“Eventually,” Brownstein writes, “I started to cringe at the elitism that was often paired with punk and the like. A movement that professed inclusiveness seemed to actually be highly exclusive, as alienating and ungraspable as many of the clubs and institutions that drove us to the fringes in the first place. One set of rules had simply been replaced by new ones, and they were just as difficult to follow.”

It’s in this willingness to belong while worrying away at the rules of belonging, that the earnest Brownstein of the memoir is reconcilable with the subculture satirist of Portlandia. Nevertheless, it’s the rock Brownstein, raw, personal and never really abandoning the project of self-examination, that wins the day here.