Review: Golden Years

While it’s impossible to know now how the book might have been received were it not for Eskandarian’s tragic and senseless end, it’s difficult not to imagine that it his death has given the book a cachet – certainly a poignancy – that it would never otherwise have had.

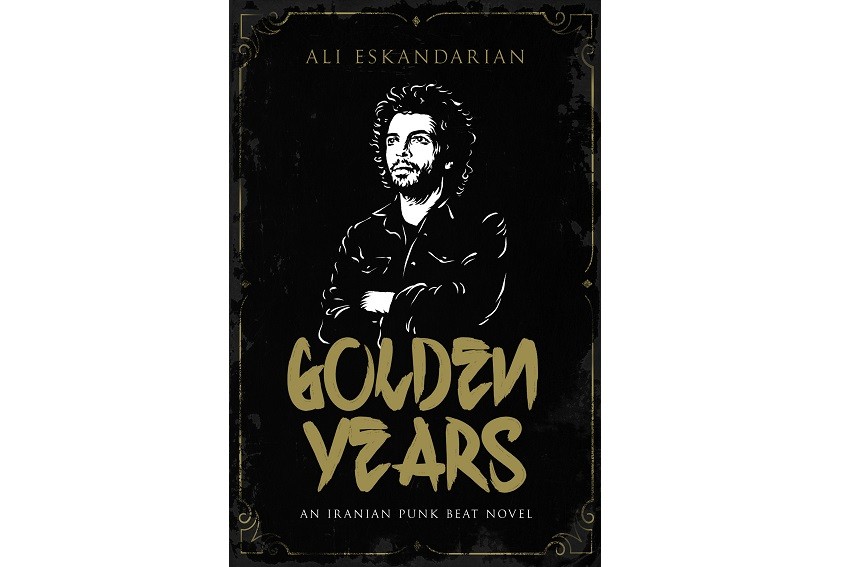

Iranian–American musician Ali Eskandarian was murdered together with two members of the Iranian band The Yellow Dogs, in Brooklyn in 2013. It was a little over a year since he’d completed the manuscript of his first – and only – novel. By the time of Eskandarian’s death, Dutch publisher Oscar van Gelderen had already begun serialising the book online under the title Golden Years. With its deliberate nod to Bowie (“Run for the shadows/ in these golden years”) it seemed a better fit than Eskandarian’s original title: American Immigrant. While it’s impossible to know now how the book might have been received were it not for Eskandarian’s tragic and senseless end, it’s difficult not to imagine that it his death has given the book a cachet – certainly a poignancy – that it would never otherwise have had. The result is a posthumously–edited and published, semi–autobiographical ‘Iranian–American beat’ novel. It is at once maddening and a joy. For much of its chaotically–structured journey through its narrator Ari’s adulthood as a struggling musician in the United States, via his childhood in Iran and post–Cold War Europe, Golden Years meanders through passages of borderline–tedious, automatic–style writing. Editor Lee Brackstone admits that he has maintained much of the prose from the original. “Sentences,” he writes in an introductory note, “are the DNA of a novel.” I suspect it will be at this genetic level that the novel will divide reader. While musical, the writing is often burdened with a propensity toward long associative lists. It’s clear that these are an attempt to capture something of the kaleidoscope of Ari’s hedonistic experiential drift through drugs, sex, love, poverty, art, music, soul-killing jobs and more drugs. But they also tend to make the writing feel bloated and pretentious. Even more difficult to warm to is the tendency for Eskandarian’s narrator to slip, particularly in those contrails of associative thinking, from free–living hedonism into claustrophobic gender attitudes. Women (often ‘females’ – which is maddeningly over–used as a noun rather than an adjective) are mostly potential sex objects upon whom he hangs sometimes retrograde categorical labels: “treacherous young witches, old sorcerers, girlfriends, daughters of the revolution, goodtiming whores, sluts, broads, intelligent ingénues, wildcats, cougars, drunkards, closet lesbians, Midwestern midwives, nurses, lawyers, painters, assistants to Congressmen, strippers, pole–dancing specialists, bohemians, yuppies, yippies, hippies, honkies, hipsters, screamers, moaners, quiet types, skinny, voluptuous, blondes, brunettes, redheads. Not that we’d gotten our end in with them all, but close.” The chase after sex, and the sex itself, doesn’t read as shocking or enlivening. Instead it leans toward the logic of a teenager’s braggadocio. The need to categorise women reveals Ari’s deep anxiety about them. Yet, it’s impossible not to admit that the sheer energy of this novel makes its parts into something more whole. For me, it was about halfway through the novel, as Eskandarian imagines he is able to imagine the perspective of a woman, to consider what it might feel like when a man is sexually obsessed with her, that it suddenly appears to accumulate some depth. Further on, Eskandarian reaches into his memories of his grandparents in Tehran and the terror of living on an air force base in Shiraz during the Iran–Iraq war. His disgust with America – his own drifting self–disgust – is painted on the background of the country’s depthlessness. It all motions to and, satisfyingly, arrives at a transcendent place, particularly on its reflections on death, with some of the book’s best writing that is – like Joyce, and yes, like the Kerouac it wants to acknowledge – truly capable of epiphany. Author: Ali Eskandarian Publisher: Faber & Faber