Review: Public Library and Other Stories

It’s as a vehicle of response to financial starvation that Ali Smith’s new collection Public Library and Other Stories asks to be read.

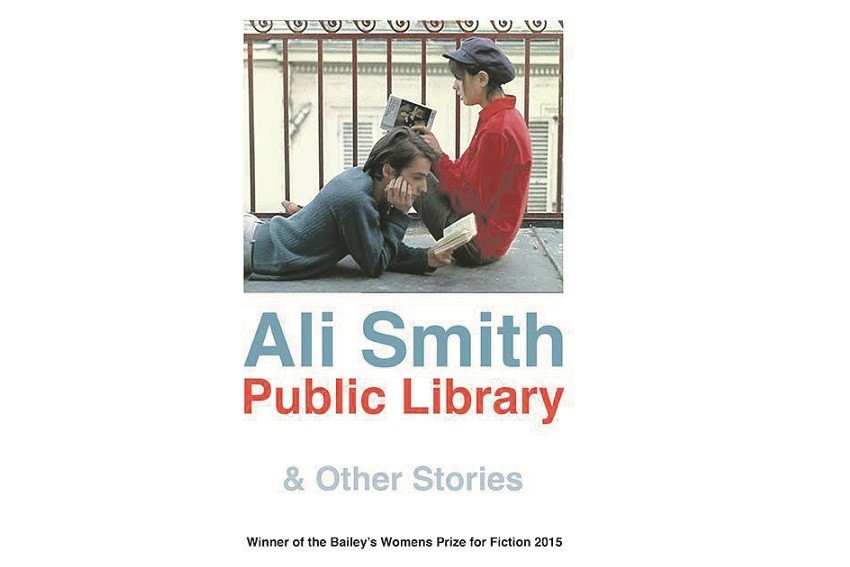

The institution of the public library has undergone a sizeable shift in recent years as it has had to re–conceive its role in a radically changed and increasingly Google-ised information cosmos. This shift has prompted questions about what the point is of these institutions with all their pesky and expensive overheads – staff, physical books, buildings – when their contents are could just as effectively be available from home. Different jurisdictions have responded in different ways. In Australia the changed set of rules has prompted something of a renaissance of the public library. In 2014 Adelaide’s City Library shifted to a new site in Rundle Mall with flexible spaces that reflect a digital and media focus. The City of Melbourne has recently opened new branches in Southbank, Carlton and the jewel in its crown, at Docklands. Built into these new spaces are areas for video gaming, a ping pong room, music studios, 3D printing labs, and a sizeable amount of shelf space for that old technology, books. Increasingly the public library is becoming a place where people come to access the free Wi–Fi, study in groups and connect with friends and communities. In the UK, however, faced with the dour self–declared imperatives of austerity, public policy makers have chosen the public library as a target for cuts and closures. It’s as a vehicle of response to this financial starvation that Ali Smith’s new collection Public Library and Other Stories asks to be read. The 12 stories in it are punctuated with the responses given by a number of people (many of whom are writers) when Smith asked them what public libraries meant to them. The stories themselves have much more to with the intimacy of words than with books and information. They’re about the way we wrestle with, are controlled by, resist, embrace and luxuriate in language. The opening story, ‘Last’, has the narrator take a train to the end of the line. When she watches it pull into a siding she sees that a woman in a wheelchair is still aboard. The narrator’s journey to the woman’s rescue traverses not only the liminal space between the designated public space of the railway station and the restricted, fenced off sidings, but also the duality of language that begins with the signs that delineate that border. Her wondering about the homophone ‘find/fined’ and the homonym ‘fine/fine’ prompts her to descend into a joyous exploration of the ‘travelling etymologies’ of the words ‘buxom’ (which originally meant ‘obedient’), ‘aloof’ and ‘clue’ and so on into a lexophile’s daydream. ‘Words,’ she has realised along the way, ‘were stories themselves.’ In ‘Speaks to the dead’, the narrator’s father maintains a visceral presence through the memory of his words and their re–collection on the page. ‘The beholder’ sees the literalisation of a metaphor in a bodily growth, a bloom. ‘The poet’ is a biographical sketch of the 20th century poet Olive Fraser, that hinges on a vividly imagined moment in Fraser’s youth in which she flings a book across the room to find it is made of musical staves. There is literally music in the book. While ‘The human claim’ is a story ostensibly about the uncertain fate of D.H. Lawrence’s ashes it manages to switch into a parody of the linguistic frustrations faced by a customer dealing with a mindless bank. Through the stories there runs a set of images and themes: the dead father, lovers and ex– lovers, lush parks, gardens and flowers, and obsessions with writers and artists (besides Lawrence and Fraser there’s Katherine Mansfield and Dusty Springfield) as unknowable, but intimately imaginable symbolic figures. Taken together they become something more than the individual parts, more than the stories’ sometimes comic or at least absurdist leanings, to form into something coherently haunting, intellectually touching. Perhaps something a little like a library collection. Author: Ali Smith Publisher: Hamish Hamilton