Sleepwalking through the dreams of Youssef Nabil

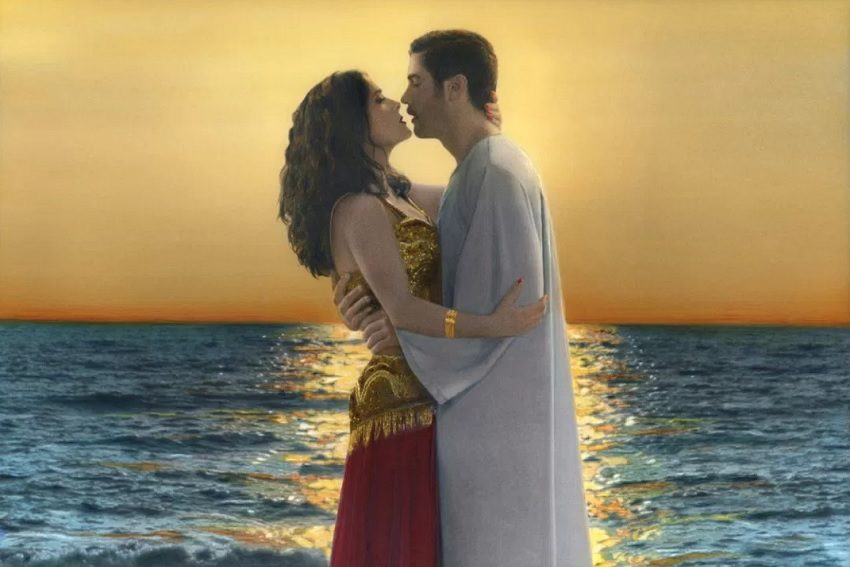

Youssef Nabil hand-colours black and white photographs to explore childhood memories, Egyptian cinema and his own personal journeys.

In 1893, a dancer named Fatima performed the ‘hoochee coochee’ or the ‘shimmer and shake’ at the Chicago World Fair. Fatima (aka Fahreda Mazar Spyropoulos) was in fact performing the ‘danse de ventre’ (literally the ’dance of the belly’) originally encountered by the French during Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt at the end of the 18th century.

Later, Spyropoulos performed in Europe under the name ‘Little Egypt’ — a soubriquet best known to many through the 1961 rock hit Little Egypt (Ying Yang) recorded by The Coasters, Elvis Presley, Cher and others. Across the first half of the 20th century, Hollywood films ensured that the ‘belly dance’ became synonymous with not only Egypt but the Arab world.

The grounds for this stereotyping had been well prepared by Orientalism, a form of art produced by Western artists in the 19th century who specialised in subjects drawn from travels in Western Asia or simply, the ‘Middle East’. From Rudolph Valentino’s 1929 film The Sheik to the present day, the Middle East, and its presumed epicentre, Egypt, have provided inexhaustible backdrops for exotic adventure and Eurocentric world-views. Youssef Nabil’s work draws on a sense of balancing the books by reaffirming the autonomy and richness of Egyptian cinema of the modern era from a complex standpoint of viewing self as other. It is intensely autobiographical.

Nabil was born in Egypt and though currently living and working out of New York, he still draws upon his sense of Egypt, and Cairo, of being home. His medium is photography. More recently he has made a series of videos. Nabil’s origins as a photographer were humble. Photography, in the Cairo of his 1980s youth, meant family portraits and weddings. Such photographs were black and white, and often hand-coloured.

Later, Nabil would seek out the last generation of photo-tinters of old Cairo to acquire related skills in colouring his own photographs using watercolour, oil and charcoal to give his images the look of portraits and movie posters from the 1940s–1960s ‘golden era’ of Egyptian cinema. This young self-taught photographer had the good fortune to separately meet two international photographers, David LaChapelle and Mario Testino, who introduced him to the photographic scene and the celebrity-driven art and fashion worlds of New York, then Paris.

A significant formative influence on Nabil’s practice was the work of Armenian-Egyptian photographer Van Leo who, early in his career, developed a passion for Hollywood movies and, associated with this, film-star postcards. Significantly, in terms of Nabil’s own creative trajectory, Van Leo produced a series of more than 400 auto (self) portraits in which he portrayed himself as a diversity of characters. In this current exhibition, Nabil casts himself as a sleeper or world wanderer.

As evident in Nabil’s photographs, Van Leo paid great attention to production aspects of sets, surrounding and lighting as well as shot angles and facial expression. Of additional significance, given Van Leo’s photo portraits of opera stars, Nabil’s has cast well-known arts identities (Catherine Deneuve, Charlotte Rampling, Nan Goldin, Salma Hayek, Marina Abramovic and others) in his photographs and videos, Van Leo took portraits of opera stars.

Growing up, Nabil watched a lot of films. This self-styled ‘visual child’ began to think about the the way the aesthetics of the presentation created an aura of glamour and intrigue. To appreciate the heartland of Nabil’s current practice it is necessary to view it through the lens of a life journey characterised by the mixed feelings of a wanderer who has embraced the wider world, yet feels a keen sense of separation from home and cherished memories of an era — a way of life — that is being eroded by the pace of change.

Nabil’s anxiety about the survival of the belly dance in contemporary Egypt is related to emerging forces, as he sees it, of conservative attitudes and systems that would deny or repress the rich heritage of traditional and modern Egypt’s liberal culture. His dancer in I Saved My Belly Dancer is a signifier of, as Nabil puts it, “how people were represented at the time”.

“Everything was beautiful, and people were more romantic. I felt that people were nicer before, and now the relationship between us is something else. So it’s about the world I grew up watching, basically, and the Egypt that I loved.”

Cast as a sleeper, or wanderer, the artist explores this sense of being cut adrift and dealing with the feeling that leaving one place for another means some part of one’s self ‘dies’. Death and sleep are so close together in Youssef Nabil’s imagery. Death in the guise of knowing that ‘I’m only here for a short period of time and then I’m leaving’ and sleep as the rehearsal for the real thing — or as Iachimo in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline has it, “thou ape of death”.

Faced with the brevity of life, little wonder that Nabil as wanderer resembles Endymion spending life in perpetual slumber to ward off age. And to share his dreams look no further than his timeless heroes and heroines, refusing to die — waiting for their next call.

Youssef Nabil: Selected Works

Greenaway Art Gallery

Until Sunday, April 1

youssefnabil.com

gagprojects.com

Header image: Youssef Nabil, I Saved My Belly dancer # I, 2015, hand coloured silver gelatin print, 27 x 40cm