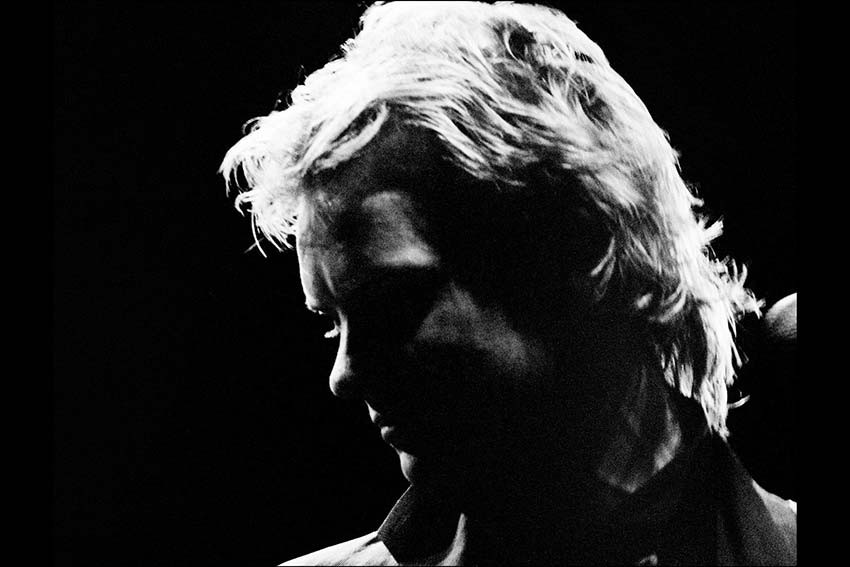

Misspent Youth by Scott Hicks

Oscar-nominated film director Scott Hicks’s early interest, while studying film and drama at Flinders University, was photography.

Oscar-nominated film director Scott Hicks’s early interest, while studying film and drama at Flinders University, was photography. Hicks documented the world around him and was particularly interested in live music and rock’n’roll. “During that time, early 70s right through to the early mid 80s, nobody really cared if you took a camera into a concert,” Hicks says. “I would barge my way down to the front and shoot away.” More than 100 of these images are on display in Hicks’ exhibition Misspent Youth at Hill Smith Gallery. What’s striking about these photographs is that 40 years later all the subjects are still at it, more or less. Hicks shot all the big names: the B52s, David Bowie, Elvis Costello, the Motels, Devo, Bob Dylan and The Rolling Stones, capturing a period when it was easy to access the stars before huge stadium shows. “It feels like a slice of history,” says the director of Shine, Snow Falling on Cedars and the upcoming Fallen. “The images of the Stones are so basic, they are like a garage band, it’s ridiculous in comparison to what their staging is like now. The images are a slice of time, like little slivers of amber. They caught something. To me they are just memories of events I really enjoyed.” The first concert he snapped was the Stones in Melbourne in 1973; he remembers sneaking in his young son Scott. This was a time before Hicks was part of the Hollywood elite, observing the world of fame from behind the lens. In an interesting turn of events, when the Stones toured in the early 2000s he was invited to supper by Mick Jagger where he confessed he sneaked his son into the concert all those years ago. Misspent Youth encapsulates a period when rock’n’roll and photography was raw and stripped back. In the way they are presented, Hicks’s images refl ect the pre-digital days, so audiences shouldn’t expect a standard, uniform photography exhibition. “These really are history and I have tried to keep the feel you get from film that you don’t get with digital,” he says. At the same time Hicks has embraced technology, playing around with scale, such as the eight-foot David Bowie print. By bringing these works to life, Hicks has immortalised these stars. “I’m intrigued by the fact that these people have become everlasting ephemera. It’s rock’n’roll, it’s pop, it’s transient but there is something oddly eternal about it at the same time,” he says. “I’m playing with that idea in the presentation and using some of my own memorabilia as a kind of adjunct to remind people.” For Hicks, photography is a much more personal pursuit than the collaborative world of filmmaking. “The darkroom has always been like a retreat. A private space in the dark, nobody else’s opinion matters, it’s just my image.” While Hicks is preoccupied with filmmaking these days, his passion for photography is still there. Viewing the images in Misspent Youth, one is conscious of the changes that have occurred in photography since the 70s, changes which have carried over into film-making. Fallen, the latest film Hicks is working on, is entirely digital. While the world of photography has changed dramatically, the essence of the medium in some ways hasn’t changed. “Everyone is a photographer now. You think of a concert: nowadays it’s 10,000 versions of that event none of which will ever see the light of day,” Hicks says. “It has become a validation of your presence, ‘I was there’… Although I guess that’s what this exhibition is – I was there. I look back on it now and it’s fantastic to remember.” Scott Hicks: Misspent Youth Hill Smith Gallery Continues until Saturday, March 28 hillsmithgallery.com.au