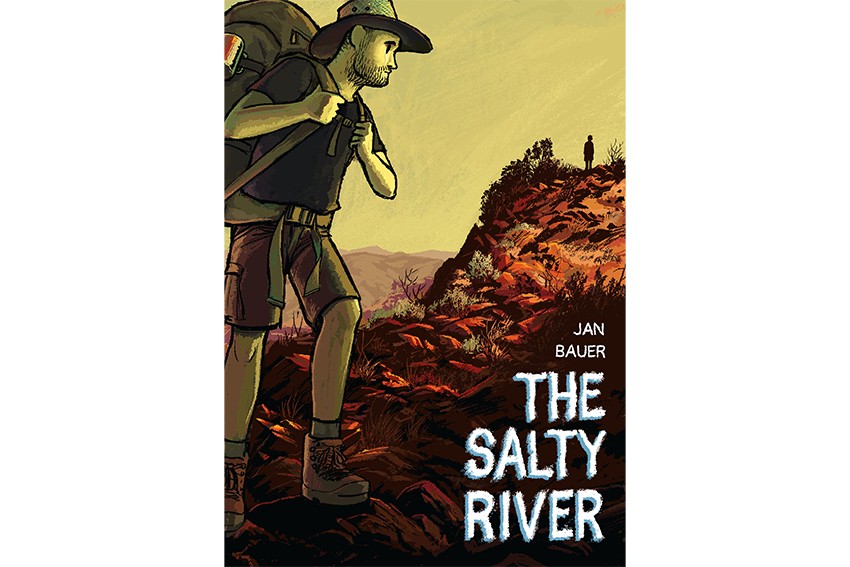

The Salty River

In his first graphic memoir, The Salty River, Hamburg-based author and illustrator Jan Bauer re-traces the gentle unfolding of a 2012 travel romance during a 500-kilometre hike along Central Australia’s Larapinta trail from Alice Springs through to Yuendemu.

In the wake of the collapse of a long-term relationship and the death of his mother, Jan sets out on his journey in mock-heroic mode, figuring himself as a literally stripped-down Spartan warrior who has descended into an epic confrontation with his most malevolent inner demons. Central Australia is the one place in the world he imagines he might be able find utter solitude and the chance to re-discover his most essential self. It’s a mark of Bauer’s self-effacing humour that his odyssey into extreme solitude, and his reverie into the darkest places of the soul, is interrupted by a set of hikers along what turns to be a fairly busy part of the trail. It’s during his effort to isolate himself still further that he chances on Morgane, a young French woman, with whom he joins first as a hiking partner and then as their affinity, friendship and intimacy develop over the days of their journey, into something more. While Morgane offers Jan a perspective on himself that lightens his mood, he remains wracked by the doubts common to the budding days of almost any relationship: does Morgane want to be his lover, or just good friends? The dominant visual mode of The Salty River is an intimate focus on its two human players as they trudge, huddle, swim and sleep their way across rocky escarpments and waterholes, campsites and dry riverbeds. These are punctuated to great effect with some stunningly sumptuous; almost realist, black and white depictions of the kinds of landscapes that Jan – and likely any other tourist to the area – yearns after. Their effect is to deliberately put into perspective Jan’s individual ego and his emotional anxieties about Morgane. In this way they make deliberate reference to the tradition of the romantic sublime. One need only think of Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog to understand just how literal some of these references are. Bauer, as framing author, narrator and character, allows himself to be taken as both earnest and endearingly ridiculous. His version of the sublime manages to both maintain the seriousness of the gaze on to the vastness of the outback world and at the same time match it up against the human negotiation being played out in miniature. It’s worth noting that The Salty River was first published in German for a German readership, and to read it in English translation for an Australian readership – this is the first title released through the new Australian imprint Twelve Panels Press – adds to it another level of perspective. It’s a reminder that Australia still stands in the European psyche for the exotic. It’s a place in which very recognisable metaphors are played out about isolation, the mystery of the unexplored, rebirth after destruction and the insignificance of the self in its struggle for significance. What saves The Salty River from being caught in the potential mawkishness of these metaphors – particularly as they meet with a love story – is that it presents them with a playful visual and narrative sense of understanding exactly what it’s doing, yet even in its moves to distance itself from the story it tells it remains deliberately honest.