My mother's wartime diaries

Part of Adelaide’s literary set of the 1940s, Carys Harding Browne wrote diaries that reveal how this fledgling group of influential writers and thinkers grew up and fell in love against a backdrop of World War II. Ann Barson, who edited the diaries for the book Carys: Diary of a Young Girl, Adelaide 1940-42, explains how she found and then edited her mother’s diaries.

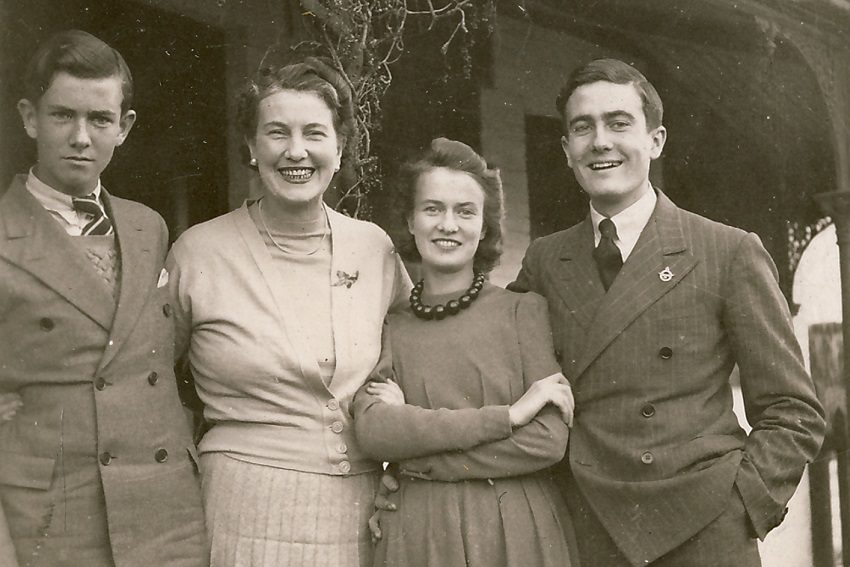

I was brought up in a home by three adults who were deeply affected by World War II – my mother Carys and her mother and my father John Portus. Carys’s two brothers died in the War, aged 19 and 21. John Portus was shot down in his Sunderland aircraft in the Bay of Biscay and half his crew perished.

Two years after my mother’s death, I was going through the family source material and was amazed to find that almost all of it was to do with the War. Diaries and letters were there, even letters written to those who had died and then returned, never having been seen by those to whom they were addressed.

I determined then to put these into a book. After a while I found the best way to do this was to use my mother’s diaries, as Carys not only writes of the impact of the War on her own family, but on others around her. For the book I used Carys’s diaries from February 1940 – when she attended her first debutante dance after leaving school – until July 1942, when she suddenly stopped writing her diaries. Carys during this time wrote from the ages of 17 until 19.

I traced her love life from her first relationship with the Angry Penguins poet, Donald Beviss ‘Sam’ Kerr, and then her love for Peter Anderson, son of the agent of the Orient Line, and finally her love for John Portus, a lawyer. I used almost all her references to the War and its growing influence on Adelaide at this time. I also included most of her descriptions of Adelaide places, cafés, restaurants, hotels and theatres. I included her ambitions to be a writer and the books she read during this time and the films she saw.

Adelaide in 1940 was a vibrant place. Clever and innovative people around the University of Adelaide throughout the ‘30s had left their mark. It was no coincidence that the Angry Penguins movement began in May 1940. This love of poetry is a theme, which keeps echoing throughout the diaries with so many people at that time keen to write or read poetry. It is a strange juxtaposition: poetry and war.

Young people courted in dilapidated old cars with no lids where girls went to dances in a velvet and tulle and a fur, taking it in turns to hold on a door. In the moonlight they climbed pomegranate trees, danced mad Russian ballets and played Noel Coward’s game, acting titles and scenes in old clothes and scarlet cloaks. They danced in the vestibule and the back verandah to the gramophone.

In the Adelaide Hills they slid down stony heights, swung from tree to tree, banged rusty tins, shouted songs and made music with a comb and a pound note. The fun continued when the American and the Dutch soldiers came to Adelaide in 1942. There were dances for them, films, trips to wineries and concerts.

I was lucky to find a tape of a talk Carys had given in 1987 about her experiences as a nurse in the Northfield Army Hospital from November 1942 until her marriage in 1944. This helped to complete Carys’s war story.

My own research showed what happened to many of the young people Carys mentioned. Elizabeth Salter went to England and became the secretary to Dame Edith Sitwell. Salter published a biography about Sitwell and then other biographies of Daisy Bates, John Peter Russell and Robert Helpmann. I also discovered that Mr Reed, the lawyer Carys worked for as a typist, became the founding director-general of ASIO. I placed my research under the heading ‘Notes’.

Finally I returned back to my own family’s source material to give the men’s last experiences of the War either from a diary extract or a letter. Their experiences were placed under the heading of ‘Other Voices’. I had interviewed Colin McArthur who was with Carys’s best friend’s brother when he was killed in the first battle of Alamein. He gave me a moving account of his death. I added an index mainly as a guide to helping the reader remember a person.

The timing of writing this book has been fortuitous. Often a diarist writes of things familiar to her which are not to the reader. I was helped to decipher these things by acquaintances of Carys still alive then.

Reading a novel is different from reading a diary. Diaries often hint at things whereas novels often over explain but maybe this is the strength of diary writing. Carys was young and impressionable but she was often shrewd and sometimes satirical. Her diaries are a treasure as they not only trace the social and cultural period of wartime Adelaide but also give her reactions to the pain of war. Growing up at this time was a mixture of fun and terrible sadness.

Carys: Diary of a young girl, Adelaide 1940-42 edited by Ann Barson, ETT Imprint, $26.99, available in all good bookshops or online at booktopia.com.au