Kylie Maslen

Kylie Maslen is a writer and critic from Kaurna/Adelaide, and the author of Show Me Where it Hurts: Living with Invisible Illness (Text Publishing).

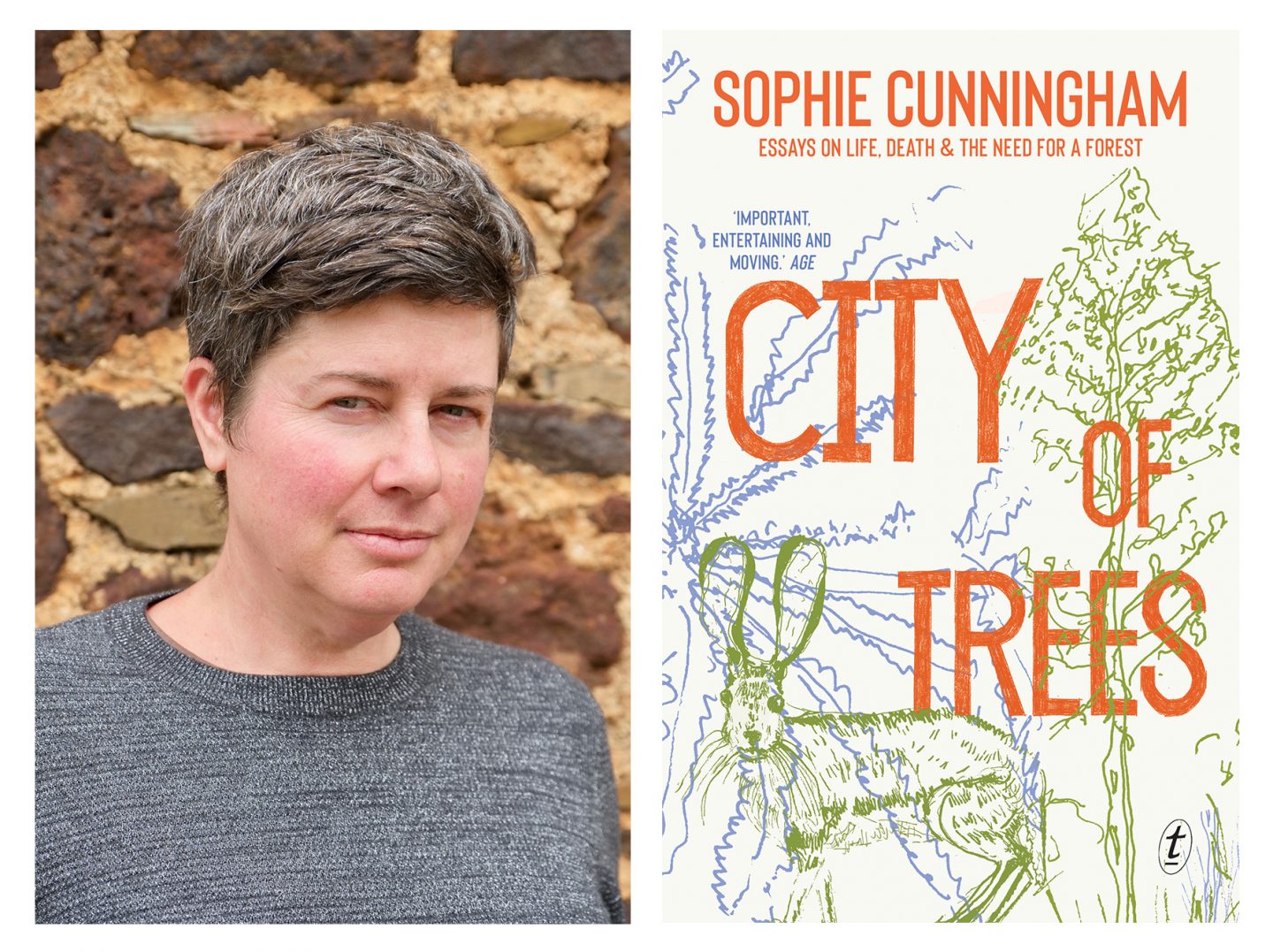

In her 2019 essay collection City of Trees, author Sophie Cunningham offers a very personal reflection on urban ecosystems, grief and culture that feels all the more timely and universal ahead of Adelaide Writers’ Week 2020.

Speaking to Sophie Cunningham ahead of her appearance at Adelaide Writers’ Week, it feels impossible not to ask her about the catastrophic climate events of this Australian summer. “I’ve been devastated to be honest,” the City of Trees author says. “I’ve been very depressed and distressed about it.” Cunningham recounts being evacuated from a campground before it was burnt and how it left her wondering about the wildlife she had seen and heard before leaving. “It’s hard not to assume the worst.”

This sentiment is pertinent to her latest book, a collection of essays ‘on life, death and the need for a forest’. A chapter on ginkgo trees features the hibakujumoku: six ginkgoes that survived the nuclear bomb dropped on the city in 1945 that are still alive today. Cunningham says she doesn’t include stories such as these ‘Survivor Trees’ to demonstrate our ability to recover from disaster, so much as to hold on to their memory.

“One of the reasons I wrote City of Trees [was] partly my growing sense of sadness that the world was changing very rapidly and that we weren’t talking about it.

“It’s certainly not like we haven’t had to deal with disasters before, but the scale of the number of people impacted is becoming exponentially larger. […] The more it happens the more you get closer to a particular ecological tipping point, an economic tipping point, a climate tipping point.”

She says the book was written from “a place both of sadness and optimism. You kind of want to be proved wrong”.

Throughout City of Trees Cunningham wrestles with the idea of responsibility, a perfect fit with this year’s festival theme of ‘Being Human’. She writes of tourism in Iceland contributing to climate change, further encouraging tourism in a problematic circle of awareness, destruction and mourning. The Great Barrier Reef is a local example of this same problem.

“In a way what I was trying to do with City of Trees,’ Cunningham says, “and a lot of other writers have been trying to do this too, has been trying to focus on the idea that the human is not the central position. That there are other things bigger than us.”

She believes that constantly questioning our position and our place – in terms of tourism, gentrification and environmental destruction (all of which are explored in the book) – is vital to this time in history. “I think these disasters do trigger a kind of greater existential crisis: What is the point of me? What can I do? It makes you think about a lot of things.”

A particularly moving essay is Cunningham’s account of being a gardening volunteer at Alcatraz National Park. “It was sort of life changing,” she says. “It wasn’t just gardening.” While the gentrification and poverty of San Francisco was confronting and fraught for her, Alcatraz “gave me a sense of community” while she was away from family, friends and writing commitments at her home base in Melbourne.

Over the course of the book Cunningham recounts the death of both her fathers, the grief of which is shadowed by environmental collapse and the global loss of forests. There is a sense of the world being unfair – the class issues at stake after an event such as a major bushfire, unprecedented loss of wildlife at the hands of one destructive species, and the cruelty of a dementia diagnosis to a loved parent – some of this within our control, some not.

The loss of her fathers challenged Cunningham in ways she had not felt before. “I’ve worked with words since I was 21 and words just weren’t cutting it for me. I couldn’t articulate my feelings. […] I moved to much more non-verbal things. Maybe that was a way of allowing the kind of shapelessness of grief to just exist.”

Cunningham says though that while “grief informed a lot of the fabric of the essays, by the end it wasn’t what I wanted the book to be about”. Instead City of Trees becomes a testimony of sorts to the importance of the detail in our lives – the people we cherish, the city we live in, the flora and fauna around us.

“One of the reasons I wrote [the book] is because if you don’t look at what’s around you, you don’t necessarily track what you’re losing.

And while it can be painful […] you’ve got more chance of not losing it if you’re doing so.”

With this in mind, Cunningham says, “I was really, really pleased when Adelaide Writers’ Week asked me [to attend] because to know that they were interested in embracing these topics. “The arts are a bit of a hot-house of both political creativity and activist creativity in terms of how one responds in these times. The arts community is really important [for] keeping these issues on track, thinking about responsiveness and trying to find a way through. This is something that writers do every day.”

Kylie Maslen is a writer and critic from Kaurna/Adelaide, and the author of Show Me Where it Hurts: Living with Invisible Illness (Text Publishing).