Walter Marsh

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

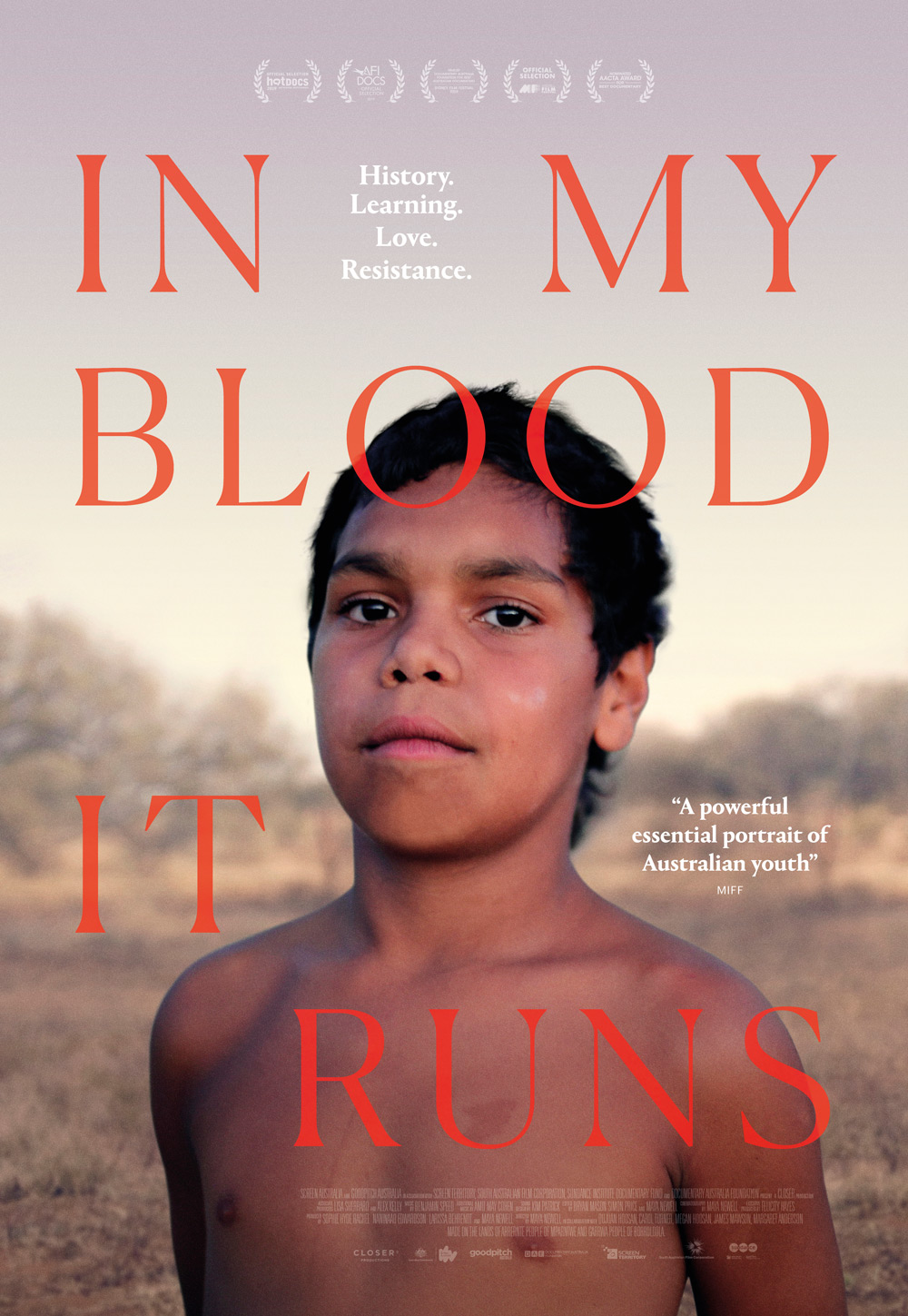

Observational documentary In My Blood It Runs is a stirring study of love and resilience in First Nations families, and the ways Australia’s education and justice systems are failing them and their children.

Back in 2015 Maya Newell’s debut film Gayby Baby was drawing praise, and a little bit of rightwing outrage, for showing the human side of Australia’s pre-postal survey marriage equality debate. At the same time, the filmmaker was keeping busy in central Australia working with Arrernte communities to help create visual records of language, culture and songlines.

“In those years I learnt so much about how young people were feeling,” Newell tells The Adelaide Review. “These are kids that maybe spoke lots of Indigenous languages, they were confident out on their county, they were enthusiastically learning songlines from grandparents, but then they were going into the western school system and feeling like failures at school. And I think that cuts to the heart of what we wanted to do with the film, to ask the question: is there another way we could be measuring success?”

Enter Alice Springs 10-year-old Dujuan Hoosan. “He bounded up, this exuberant, intelligent, cheeky young kid with just this beautiful way of articulating the complex world around him; he has this moral code and poeticism in the way he sees the world – and he also just really wanted a film made about him. I thought, what a beautiful conduit he could be for wider Australia to be let in to learn more about what it is to be a First Nations person, but in particular a child growing up in these systems that often feel like they’re out to get you.”

As the film begins we meet Dujuan as he picks bush medicine and helps practice traditional healing on members of his family. But we soon see he is pulled between two different worlds. In Alice Springs, he struggles to engage with an English-based school curriculum he feels is disconnected from his own life, history and culture. But, on a trip back to their ancestral homeland at Sandy Bore, we watch him switch back to English as he finds it difficult to keep up with the fluent Arrernte spoken around him. His grandmother Carol looks on, having been forced to uproot the family from their homeland to secure her grandchildren’s ‘education’ in Alice Springs, only to see their own cultural learning suffer as a result.

“Early on in the project Dujuan’s great grandmother Margaret Kemarre Turner articulated this in a way that just cut through: she said, ‘they’re always telling us to make our children ready for school, but when are they going to make schools ready for our children?’ And I think that really articulates the issue that we face: how can we build systems that create space for First Nations identities, languages and culture to thrive?

“Language is important to all of us, and what Dujuan’s grandmother and family is asking for is very basic. It’s for their children to learn in their first language, and their first culture, which is what every child in Australia from an Anglo background receives every day. They’re asking for the same, to be treated equally.”

Throughout the film we glimpse news reports of the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre scandal unfolding in the background. As Dujuan’s grades suffer and he begins to act out, run away, and face the consequences, we see how the system can on many levels disproportionally escalate behavioural problems and send kids towards police custody. It’s these kinds of pathways, Newell says, that give us shocking numbers like Indigenous kids comprising 100 per cent of detainees in the Northern Territory.

“We started filming when the allegations about Don Dale came out on 4 Corners, the torture of Aboriginal children,” Newell says. “We remember that moment as a country, I think, most people remember being shocked by those images and the treatment of children like Dylan Voller. But I don’t think many of us imagined what it would feel like to be a 10-year-old child watching that, when you know members of your family who have been or are in Don Dale, and you’re currently in a situation where systems are bearing down on you and that future is a very possible reality.”

In My Blood It Runs holds its sense of history close, but while the film takes care to place Dujuan’s story in the context of 20th assimilation policies and forced child removals, Newell says his experience reflects a particularly regressive moment. We only need to look to 2018 comments from then-Indigenous envoy Tony Abbott that Aboriginal kids should not only speak, but “think” in English, to see how a grave blend of paternalism and casual cultural erasure continues to influence policy.

“We’ve actually had much more progressive moments in our history around the Territory,” she says. “There was an incredible movement of bilingual and bicultural schools in the 80s that were specifically torn down by government policies.”

Throughout the film we see the world from Dujuan’s perspective – often literally at his eye level. To avoid adding to a media narrative that is often quick to judge and vilify non-white young people, Newell worked with Dujuan’s family and community from the outset to find a “strength-based” model for telling their story, steeped in collaboration and consultation. Newell relocated to Alice Springs for two years during the project, supported by Adelaide’s Closer Productions and producer Sophie Hyde (whose naturalistic debut 52 Tuesdays the film occasionally evokes) along the way.

“I knew how it felt from my first film Gayby Baby of how it felt to be misrepresented,” she says of the politics of representation. “And First Nations people have had their stories extracted and appropriated since the beginning of colonisation.

“I really believe that with documentaries often the quality of what you see onscreen – the story, the intimacy, the relationships – are only possible because of the relationships that occur offscreen. It’s been commented that there’s an intimacy to this film, it’s not your average talking head documentary that tells you how to think. It’s very observational – the camera is quite literally 30cm from Dujuan’s face most of the time, sitting with him, walking with him.

“I think children actually have a lot to teach adults, and children, not just Dujuan, have an intelligence that we lose as we get older,” she reflects. :From a filmmaking perspective it was our intention to have the camera’s eye at Dujuan’s eyeview, so you’re seeing the world from his level.

“You’re with him, not looking down at him.”

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.