Golem: Invasive Technology and the Monster in Your Pocket

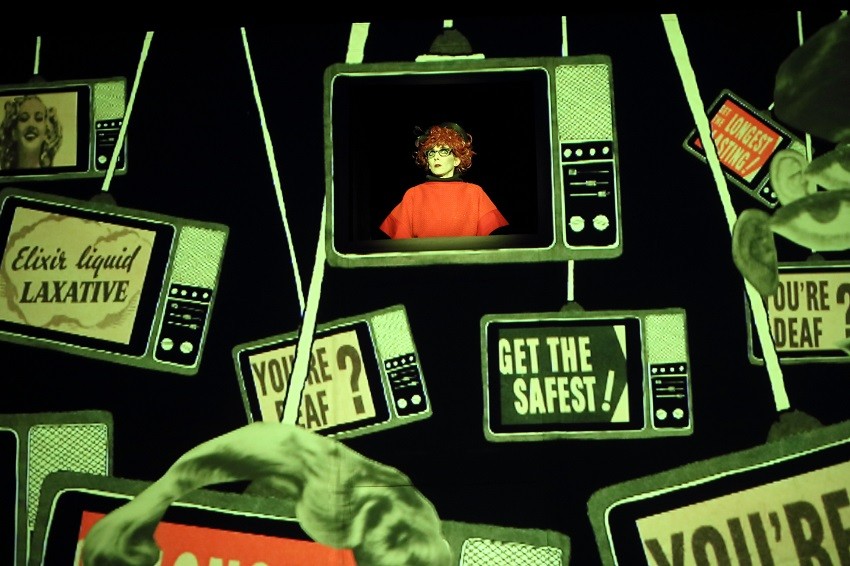

A dizzying and occasionally foreboding mess of animation, music and physical theatre, Golem is perhaps one of the more playful inclusions in this year’s Adelaide Festival program dominated by alt. rock giants and epic all-day-and-night Scottish plays.

The work of London company 1927, the play adapts and remoulds the old Jewish legend of the Golem into an artful parable about our own addiction to modern technology. But rather than drawing inspiration from the legend, or Gustav Meyrink‘s 1914 novel, the concept sprung from their ongoing experiments in eccentric, art form-blurring theatre. “It wasn’t initially our intention I suppose,” co-writer and director Suzanne Andrade says ahead of Golem’s Adelaide debut. “We were very taken and inspired by the idea of a live actor on stage and this clay man, and the relationship between the two of them. That was the starting point,” she says. “Then from that we started creating synopses and various stories and we created other characters, worked on this main character who has a Golem, started talking about how he might get a Golem and so we wrote loads.”  “Our creative process is really long, and meandering like a river,” she says. Eventually though, they struck gold. Or clay, as it where. “[It was] through going back through the original research of that Jewish story that I was led to artificial intelligence and cloning and robots, and also I was just looking around at my mates and how obsessed they were with their phones. Then it just started to come together really, and we started lacing together this story about our obsession and increasing reliance on our invasive technology. But while the clay figure was a starting point, the company’s distinctive blend of projected animation, live acting and music means the finished product of Golem is a long way from an episode of Morph. “Clay itself is such a sort of organic material and one that doesn’t fit into a story about modern technology – it’s so opposite to a freakin’ iPhone that it was quite interesting for us,” she says. “Clay was definitely a driving factor but has ended up being one part of this mad collage with so many different styles of animation.”

“Our creative process is really long, and meandering like a river,” she says. Eventually though, they struck gold. Or clay, as it where. “[It was] through going back through the original research of that Jewish story that I was led to artificial intelligence and cloning and robots, and also I was just looking around at my mates and how obsessed they were with their phones. Then it just started to come together really, and we started lacing together this story about our obsession and increasing reliance on our invasive technology. But while the clay figure was a starting point, the company’s distinctive blend of projected animation, live acting and music means the finished product of Golem is a long way from an episode of Morph. “Clay itself is such a sort of organic material and one that doesn’t fit into a story about modern technology – it’s so opposite to a freakin’ iPhone that it was quite interesting for us,” she says. “Clay was definitely a driving factor but has ended up being one part of this mad collage with so many different styles of animation.”  For a piece so focussed on our increasingly symbiotic relationship with tiny black mirrors, we were intrigued how the piece would fly in the theatre – perhaps one of the final frontiers where ever-eroded sense of phone etiquette still hangs on. Or so we thought. “I’ve got to say it’s been quite a long time since I’ve been in a theatre audience and not seen someone on their phone,” she reflects. “I think the culture’s a bit shit. There’s a moment when the show’s about to begin and everyone’s on their phones, and thousands of tiny screens light up. “It’s something I’ve always found really odd,” she explains. “People don’t turn off before they go into the theatre these days; they wait until the very last second. So already their minds aren’t quite on it, they’ve not dropped it at the door, and phones are constantly going off – I’ve even sat watching Golem in the theatre in London and I’ll see little screens popping up, people just checking the time, just checking the status. So I don’t know!” At least the show’s content is usually effective in messing with audiences’ habits by curtain call, even if their subconscious hasn’t yet embraced the message. “There’s definitely that moment when most people switch the phone back on at the end of the show,” she says. “It’s quite interesting how audiences react to that, where they go ‘Oh my god I’ve just checked my phone straight away, I’m obsessed with my Golem!’ There’s those kind of interesting moments, that switch on moment is always quite exciting to see. The culmination of years of experimentation and refinement, punctuated by some creatively necessary rule breaking, 1927’s visual style is influenced by many styles and genres, but even at its most text heavy moments seems to convey a certain non-verbal, physical storytelling that harks back to the silent film era. It’s something Andrade is keen to pursue in future projects. “Our stuff is always very inspired by silent film and performances, and that reads really clearly I think wherever you are in the world,” she says. “We’re yet to create it but it’s very much on the cards, a show that let’s say is more for Indigenous communities but could also work in Sydney or Melbourne and in Adelaide,” she says. “But could also go to somewhere really obscure in Russia, so that silent film language could be even stronger. We’re discussing that at the moment.” Golem Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre Daily until Sunday, March 13 adelaidefestival.com.au Photos: Tony Lewis

For a piece so focussed on our increasingly symbiotic relationship with tiny black mirrors, we were intrigued how the piece would fly in the theatre – perhaps one of the final frontiers where ever-eroded sense of phone etiquette still hangs on. Or so we thought. “I’ve got to say it’s been quite a long time since I’ve been in a theatre audience and not seen someone on their phone,” she reflects. “I think the culture’s a bit shit. There’s a moment when the show’s about to begin and everyone’s on their phones, and thousands of tiny screens light up. “It’s something I’ve always found really odd,” she explains. “People don’t turn off before they go into the theatre these days; they wait until the very last second. So already their minds aren’t quite on it, they’ve not dropped it at the door, and phones are constantly going off – I’ve even sat watching Golem in the theatre in London and I’ll see little screens popping up, people just checking the time, just checking the status. So I don’t know!” At least the show’s content is usually effective in messing with audiences’ habits by curtain call, even if their subconscious hasn’t yet embraced the message. “There’s definitely that moment when most people switch the phone back on at the end of the show,” she says. “It’s quite interesting how audiences react to that, where they go ‘Oh my god I’ve just checked my phone straight away, I’m obsessed with my Golem!’ There’s those kind of interesting moments, that switch on moment is always quite exciting to see. The culmination of years of experimentation and refinement, punctuated by some creatively necessary rule breaking, 1927’s visual style is influenced by many styles and genres, but even at its most text heavy moments seems to convey a certain non-verbal, physical storytelling that harks back to the silent film era. It’s something Andrade is keen to pursue in future projects. “Our stuff is always very inspired by silent film and performances, and that reads really clearly I think wherever you are in the world,” she says. “We’re yet to create it but it’s very much on the cards, a show that let’s say is more for Indigenous communities but could also work in Sydney or Melbourne and in Adelaide,” she says. “But could also go to somewhere really obscure in Russia, so that silent film language could be even stronger. We’re discussing that at the moment.” Golem Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre Daily until Sunday, March 13 adelaidefestival.com.au Photos: Tony Lewis