Tale of the Century

Bicycle-tinny hybrids and Westworld-inspired audio tours are just the tip of the melting iceberg for Vitalstatistix’s playful, thought-provoking Climate Century festival.

By now there’s little doubt the looming effects of climate change will be era defining, but for a Port Adelaide based arts organisation like Vitalstatistix the challenges of the next century are more than existential. “If you look at projections for 50 years’ time, the worst projections are that most of the Port and Lefevre Peninsula are underwater,” Director Emma Webb says.

Perhaps it’s no surprise then that Webb and her team have made this pointy end of the anthropocene the focus of a five-year long project. “It’s actually communities who have to face climate change who do come up with the most interesting campaigns and strategies,” she explains. “I certainly think that’s the case for people who are living in Pacific Islands, it’s often the case for regional communities and certainly for us in Port Adelaide, the weather impacts and rising water impacts of climate change are more obvious.”

Originally, Webb was inspired by another planet-shaking turning point. “I was quite interested in 2013 as we led into the centenary of World War One, of how the previous century and the anniversary of World War One was being spoken about and memorialised,” she says. “It made me think about what we might be looking back on in 100 years’ time, and how we might memorialise but also consider what has happened in that period of time.”

Across three weeks in November, Climate Century will see eight multidisciplinary works tackle those very questions. Following a more locally-focussed program in 2015, this second and final instalment invites artists from around the country to transform the Waterside Workers Hall and its surrounds with installations, performances and workshops. But it isn’t necessarily a program driven solely by themes of protest or evangelisation. Climate Century features works that are by turns playful, thought-provoking and, importantly, unlikely to spook audiences into a depressed fugue – a real challenge for many conversations around climate.

“It’s not about making a series of works aimed at influencing individual behavioural changes,” Webb explains. “Artists are adept at communicating complex messages and having a really effective impact on people, and that’s important, but for me that’s not the role of this festival. These works are deeply personal to all these artists. They’re embedded in campaigns and ideas around justice and touching on a whole lot of complex ideas that do give us some sense of how we can respond to climate change in more radical, speculative and imaginative kinds of ways.”

Just as climate change promises to be transformative, several works creatively reinterpret the waterside setting of the Port itself. Raft of The Medusa by Pony Express offers a novel spin on a Port River cruise, commandeering the South Australian Maritime Museum’s 76-year-old ex-navy vessel the Archie Badenoch for a voyage Webb describes as a “sharp and witty political work”.

Musical duo Winter Witches plan to address the environmental impact of the meat industry – itself strongly linked to the Port through the live export trade – in a “beautiful, hopeful eulogy to individual animals”. And Jason Dodd’s River Cycle will showcase the artist and inventor’s bicycle powered dinghy hybrid, which will be on display having pedalled its way through the Murray, Onkaparinga, Patawalonga and Torrens rivers.

Meanwhile, Sandpit’s Eyes uses an innovative combination of live and pre-recorded audio to walk audiences through a post-apocalyptic landscape super imposed over the Port itself. “Part of the premise of Eyes is it’s an immersive tour of the end of the world,” says co-director Sam Haren, “and the conceit is that you can hear this world but you can’t see it. It’s an imaginative exercise at play where we’re highlighting a dramatic tension between what you might hear and imagine in the space versus what you can actually see. It will hopefully be an interesting focus to take audiences through the Port where these events and things are present through sound, but not visually.

“We approached Eyes thinking that people are interested in playing out and simulating these extreme imaginings that push out our view of the world into other spaces,” he says. “When we were making the show we were referencing HBO’s Westworld, which is this idea of going into a simulation, where visitors are getting to play out this fantasy. This idea of how you can experience something, and what’s real and what’s not is a core interest to the show.”

Another key work is Sydney performance artist Latai Taumoepeau’s War Dance of the Final Frontier. “[Taumoepeau] is making an incredible video work drawing on war dances and looking at a collective body that can combat a climate century monster,” Webb explains. “It’s very much inspired by the real campaigns and resistance that is happening to the way that climate change is affecting Pacific Island nations and communities, but also how the South Pacific Ocean is being used as a laboratory to experiment with deep sea mining.”

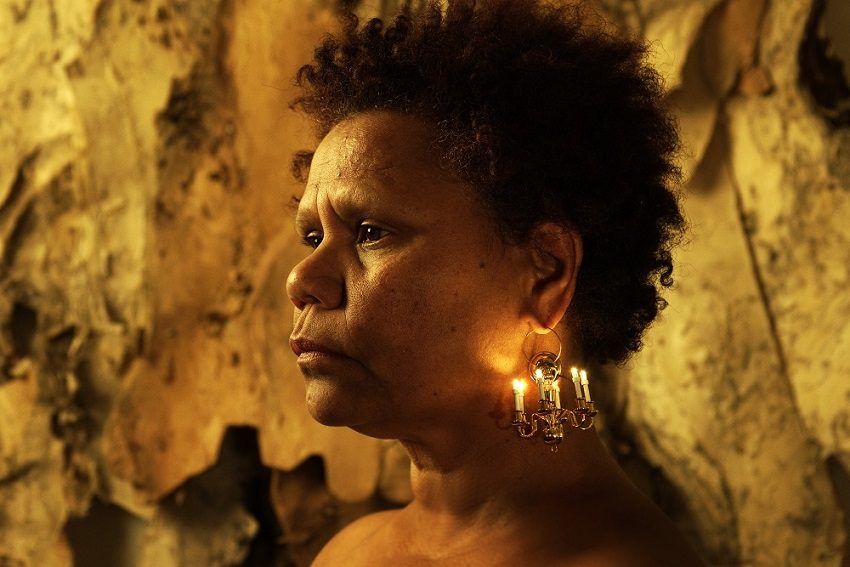

South Australia’s Unbound Collective will conclude a trilogy of works interrogating power, culture and freedom with Sovereign Acts III: REFUSE. “Unbound Collective are a fantastic collective of four First Nations women who make a lot of incredible work around environmental justice and the role of women, Aboriginal women, in environmental movements,” Webb says. With a focus on community action and reasserting sovereignty through protest, the one night only event cuts to heart of festival’s message.

The festival is timely, after an October IPCC report highlighted the critical nature of the next 12 years in the strongest terms. The news was largely met by that now-automatic mix of apathy and denial by Australia’s government and mainstream media. So a decade after the 2007 Federal Election saw meaningful climate action promised by both sides of politics, how can artists resonate where scientists, commentators and activists have struggled?

“It’s this fascinating world we live in where this paradox continues between the reality of the science and the political inconveniences of thinking about climate change,” Haren says. “Throughout history art is not willing to accept the denial of things going on in our cultural world, and it seems to make a lot of sense that there’s a whole set of ruminations around the profound importance that these ideas have.”

Webb echoes a similar point. “I think that there’s a whole range of artists in Australia and globally who are starting the most interesting conversations and cultural interventions into how we might survive the climate change condition. I think that’s because artists do have this permission, in a way scientists also have [it], of being speculative and wild and to really throw things up in the air. Some of the best climate change art occurs within an experimental arts space, where artists have that permission to think really radicall.”

“There’s this active denial that is fuelling artists to not let it get talked out of reality,” Haren says. “Which is sometimes how it feels.”

Climate Century: A festival of art for the 21st century

November 8 – 25

Waterside, Hart’s Mill and surrounds

vitalstatistix.com.au

Header image:

Unbound Collective