Appreciating Christopher Orchard's Hiss and Growl

Are the secrets to the work of one of Australia’s most formative figurative artists, Christopher Orchard, uncovered with this year’s SALA monograph?

Christopher Orchard believes that art making is about making art. Or as Degas reminded the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, “You can’t make a poem with ideas … you make it with words.” This means conjuring images from dumb materials like charcoal, graphite and paper. To let the materials have their say. Peter Goldsworthy, one of the contributors to the just-published SALA/Wakefield publication, Christopher Orchard: The Uncertainty of the Poet, nails this in one of his poems, Promenade: Three Odes to Charcoal:

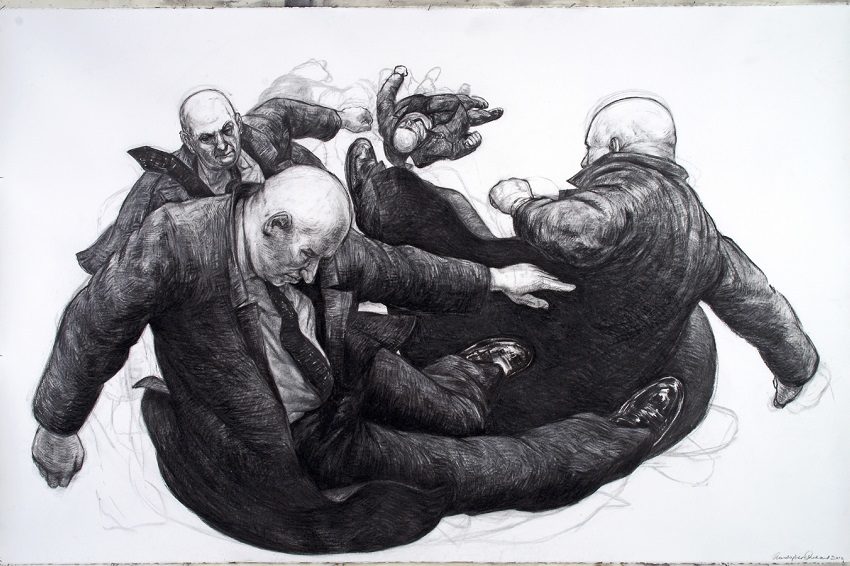

“To draw with charcoal/is to fight the canvas/with both hands tied/behind your back./Even using all seven/fingers of colour/it’s a hard fight, but this/contest I admire most:/the formal constraint/of the head-butt,/the blunt object/of the charcoal stick/smiting the white.”

Another contributor, Roy Ananda, talks about Orchard’s “constant prodding, punching and provocation of the picture plane”. It’s a battlefield. Henri Matisse once said, “Unless I wake up with the urge to kill somebody, I can’t work.” This sense of pent-up urgency, of seeing art making as a matter of life and death, is always there in Orchards’ imagery — akin to Brett Whiteley’s “inexplicably beautiful system rotating around the terror of nothing”.

Christopher Orchard, The Runner

Christopher Orchard, The Runner

With the publication of this extensively illustrated publication and insightful contributions by long term observers and associates — Peter Goldsworthy, Margot Osborne, Roy Ananda, Julia Robinson and Rod Taylor — it would seem that the balloon is finally up. Now, it seems, we can be privy to its secrets and the real reason why Orchard has been so attached to his cast of characters — particularly the little Bald Man.

Osborne’s narrative provides an accessible context to the evolution of such motifs. It is an extensive back story. A number of earlier works, drawn over a two-year period in Berry Street Studios in London in the mid-1980s, reveal something of what he regards as his “fight with the figure” – a struggle to find a certain kind of avatar.

Christopher Orchard, Small levitation

Christopher Orchard, Small levitation

Orchard initially populated his surreal de Chirico-inflected interiors and plazas with a youthful, suited male that many observers read as self-portraiture. While in London he came into contact with the Portuguese-born artist Paula Rego whose magic-realist figurative images opened windows in Orchard’s imagination.

Later, in 2000, Orchard was struck by figures seen below his Gunnery Studio window and began instinctively to draw them. At this time, he became familiar with the work of the South African artist, William Kentridge. Orchard sensed a kindred spirit in the primacy Kentridge afforded both mark-making and memory-based imagery, set within a dystopic urban landscape. Here was this dialogue between surface and symbol Orchard had been searching for. Around 2005, the artist began to recognise the authority of what he had created. “Technically,” he says, “it was there, and probably had enough meat on the bone to carry whatever it needed.” He has continued to draw this bald-headed figure hundreds of times from sketches to large scale fully worked charcoals and pastels.

Christopher Orchard: The Uncertainty of the Poet (Wakefield Press)

Christopher Orchard: The Uncertainty of the Poet (Wakefield Press)

Orchard was at the crossroads around the mid-1990s. He had created a body of distinctive imagery that relied on well-established surrealist dynamics and formulas to enchant a growing body of followers and collectors. Potentially a career cul-de-sac beckoned. But, belief in Matisse’s dictum that “an artist should never be a prisoner of himself” paid dividends. In a break out succession of imagery, Orchard’s figures shuffled as it were onto the stage.

They comprise a diverse cast of characters: Commedia dell’arte buffoons, Punch and Judy knockabouts and men who could have stepped out of ancient Egyptian stone reliefs or the pages of The Wall Street Journal. It is their behaviour that confirmed a sense of absurdist parody more in keeping with Waiting for Godot. As they act out a number of nonsensical rituals, they rediscover the toys of childhood and are tasked deploying signage, fencing-off areas with bunting, measuring, testing and relocating equipment. They rake the distance with binoculars, ascend tall ladders, poke their noses into dark recesses and tote heavy loads.

Christopher Orchard, Blind

Figures swoop and hover like Baroque fresco extras. In the relentless glare of a spotlight, individual figures bare their souls like corporate crooks caught in an ICAC sting. So, that’s it is it — just another portrayal of the contemporary human condition as an existentialist bun fight without rhyme and reason? Julia Robinson suggests that it’s more complex and personal than that. She regards the various characters — the trickster, itinerant, researcher, orator and seer as devices for the artist to fulfill a desire to be, or experience what it is like, to be a number of different personas. Ananda writes at a tangent to this perspective by suggesting that it is not only a play of personas but of pictorial space, as seen in Orchard’s constant gaming of illusionism and surface materiality, that reveal drawing’s ability to “articulate both the physical and metaphysical spaces that house human experience”.

Taylor emphasises Orchard’s adoption of a mode of mark making designed to reveal essential, even ‘timeless’ form. This brings us back to the heartland of Orchard’s practice. Where many will seek and find some social message in what appear to be little morality plays or proverbs for a modern age, others will sense uncertainty and ambiguity. As Kentridge has it, “The uncertain and imprecise ways of constructing a drawing is sometimes a model of how to construct meaning … The ethical and moral questions … in our heads seem to rise to the surface as a consequence of the process.”

So this is it — the long awaited publication on one of Australia’s foremost figurative artists. Is everything now revealed? Does it break open the innermost Russian Doll of Orchard’s symbolic universe? Maybe. Better to lend an ear to the hiss of graphite and the growling of charcoal on paper. And remember Degas’ advice “when you always make your meaning perfectly plain you end up boring people”.

Christopher Orchard: The Uncertainty of the Poet (Wakefield Press)

Solo exhibitions

Avatar

Art Gallery of South Australia

Friday, July 28 to Sunday, September 3

artgallery.sa.gov.au

Then and Now

BMG Art Gallery, 444 South Road

Friday, August 4 to Saturday, August 26

bmgart.com.au