Walter Marsh

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

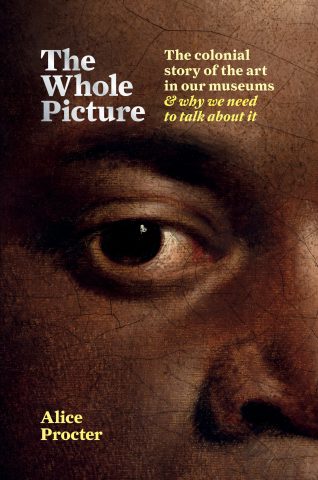

With her Uncomfortable Art tours, Australian art historian Alice Procter is making Britain’s biggest institutions confront home truths one guerrilla tour at a time.

“I had this feeling that here was this whole conversation about colonial history that no one was willing to have,” Procter tells The Adelaide Review during a brief visit to Adelaide.

Studying art history and frustrated by front-of-house roles in cultural institutions that discouraged straying from the official – and incomplete – script, Procter began leading pop-up tours of the National Gallery and Tate Britain. “When I started the tours, they were secret, nobody knew about them at all,” she says. “I was very much interested in painting collections, specifically looking at art and where the money comes from.”

Demand quickly saw Procter include four more sites, tapping into a growing appetite for the alternative and untold stories living between the lines of the typical interpretive label. “I originally thought you wouldn’t need me to show you around the British Museum – surely it’s so obvious that everything is stolen,” she says. “But I realised that most people knew that but didn’t know what to do with that information.

“To me there was a really obvious story to be told; in the UK a lot of people see colonialism as something that happened elsewhere, you don’t have the same situation as in Australia or other settler colonies where there is an Indigenous population who have survived this history of imperialism. There are obviously diasporic communities and people who have immigrated to the UK from post-imperial nations, but it’s treated in history curriculums and museums as something that happened over there, and isn’t our problem.”

“I get away with a lot in museums because gallery attendants see me and think I’m just another official, professional tour guide leading another group.”

We speak across a glossy antique table in Ayers House Museum, watched over by portraits of Matthew Flinders, Queen Victoria and other painted statesmen. A lavish mansion built by 19th century premier, mining magnate and former Uluru namesake Sir Henry Ayers, it’s an institution that has been working to unpack its own colonial ties. It was also the one-time home of Procter’s grandmother during its time as a nurses’ quarters, and her Australian upbringing has had a strong influence on her work.

“My parents wanted to make sure when we were growing up that we were very aware of our connections to colonial history. I knew from a very young age that I would not exist without colonialism or imperialism – that my great-grandparents had immigrated to Australia as settlers, as colonists, and that they had created lives for themselves here at the expense of what was here before.”

Procter is careful not to position herself as a ‘white saviour’ . Conversations around decolonising museums have been ongoing for years, she says, led by museum professionals and visitors of colour. In 2018, that conversation hit popular culture with Ryan Coogler’s Marvel blockbuster Black Panther, which opened with Michael B Jordan’s iconoclastic antagonist questioning the provenance of African artefacts in a thinly veiled stand-in for the British Museum. But, Procter argues, it shouldn’t be the sole responsibility of the historically oppressed to unpick the effects of colonialism: it’s time for the beneficiaries of imperialism to show solidarity, and do the work, too.

“I get away with a lot in museums because gallery attendants see me and think I’m just another official, professional tour guide leading another group. They don’t look twice, because I can be a ‘nice little white girl with an art history degree’ and no one blinks at that,” she says, citing recent studies into how subconscious bias and racial profiling work in a museum setting. “I go through my life in a little bubble of privilege that I’m very aware of, and I realised quite quickly while doing the tours that I could bring people into that bubble – a kind of trojan horse activism.”

There are lessons that South Australia can learn, too; while local institutions like the Art Gallery of South Australia and the South Australian Museum have made moves to repatriate certain disputed objects, the culture wars that flare up in comment sections whenever the integrity of Captain Cook is publicly questioned shows we still have some way to go.

“It’s the most important form of outreach museums and galleries have going for them at the moment, and it’s not even being done by museums. There’s this appetite, and the fact that I as one person running six small tours have had this kind of response, and museums in the UK and this country aren’t immediately saying ‘we can do that!’ says a lot.

“They need to recognise that now is a great moment to lead the way.”

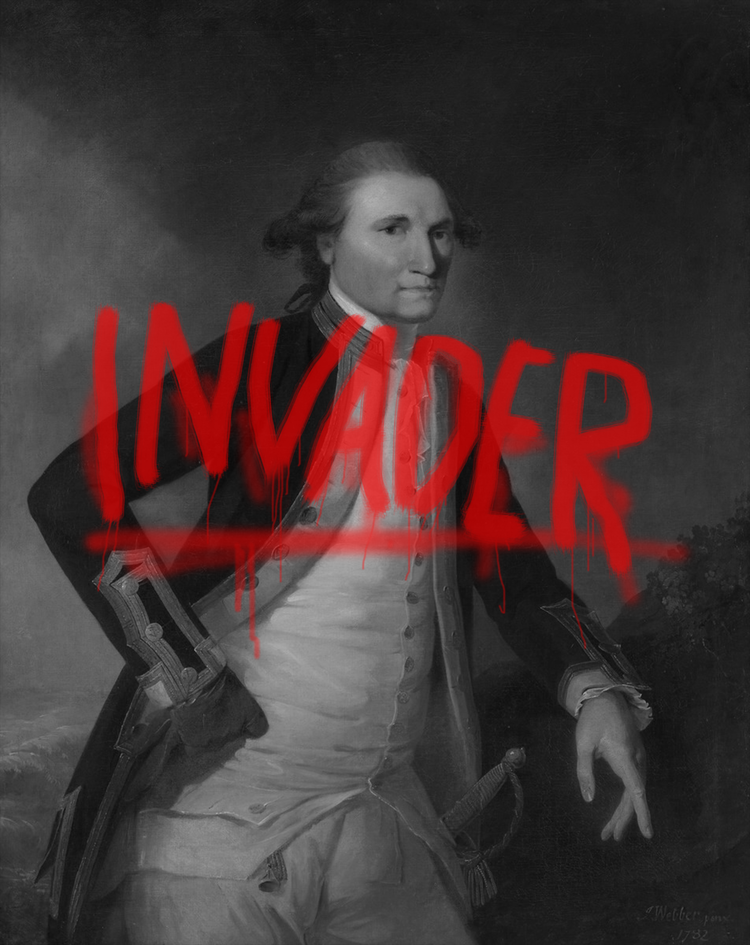

With a name like ‘Uncomfortable Art’ and playfully provocative branding (Procter distributes badges with the slogan ‘Display it Like You Stole It’), Procter’s work has seen her profiled by the New York Times and attacked by The Daily Mail. And while her tours have made some sites and guests uneasy, sometimes that’s the only way to provoke real reflection.

“Do you feel comfortable in an art gallery?” she asks. “Why is that? Is it because your family took you there when you were little? Is it because every face on the wall is the same colour as yours?

“If you don’t feel comfortable with certain histories, you have to ask yourself why and what that says. Why is it so hard to hear some narratives?”

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.