John Neylon

John Neylon is an award-winning art critic and the author of several books on South Australian artists including Hans Heysen: Into The Light (2004), Aldo Iacobelli: I love painting (2006), and Robert Hannaford: Natural Eye (2007).

The high stakes of community-based, socially engaged art are well-represented in Tarnanthi 2019 exhibition No Black Seas.

The American artist and writer Dan Graham comments, “All artists are alike. They dream of doing something that’s more social, more collaborative, more real than art.” So too, it could be added, arts agencies. Claire Bishop, in her book, Artificial Hells, notes that since the early 1990s there has been a global surge of interest in participation and collaborations under a variety of names including socially engaged art, interventionist art and social practice. Bishop says that until the 1990s community-based art was confined to the edges of the art world but it is now “a genre in its own right”, embedded within it. The commercial art world has understandably found it difficult to engage with such art but, through the medium of alternative art and community spaces, public commissions, biennales, themed festivals and the like, socially engaged art has been able to reach wide public audiences. The kind of art that gets presented at such events invariably disrupts or circumvents the usual artist/art work/audience arrangements. Audiences are treated within these situations as participants, rather than passive viewers. All well and good – but the stakes are high.

If a street protest march and an art space project have the same agenda (e.g. ‘No Fracking’) does it really matter what means are used to a common end? It might also be argued that if a street event attracts 500 marchers, 5000 onlookers and a 24-hour news cycle audience, and an art space has 500 visitors over a three-week cycle, has the art space failed in its respective efforts to win hearts and minds for the cause? Why go to all the bother of aestheticising the message?

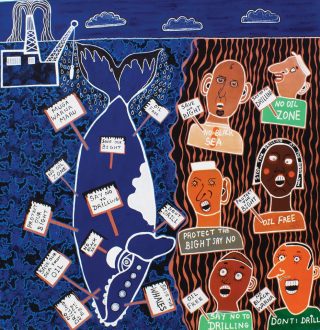

ACE Open, in presenting No Black Seas, finds itself in this situation of showcasing art intended to make some social and political difference. Its packaging of the project as “a cultural and artistic critique” of the proposed drilling in the Great Australian Bight indicates its awareness of the delicacy of the operation. A wall of posters and banners might convey a message, but not the essential one the artists, their communities, ACE and supporting agencies want to convey. This message and the heartland of the entire project is to foreground not just the massive threat posed to marine species by the Norwegian company Equinor’s drilling proposal, but its impact on the Matutjara, Mirning, Kokatha, Yindjibarndia and Wirangu peoples whose cultural identity is intrinsically linked to the the Great Australian Bight, its waters and surrounding country.

No Black Seas is a collaboration between ACE Open, Arts Ceduna and KuArts, with support from Tarnanthi. This project has seen mentor artists Yhonnie Scarce (Kokatha/Nukunu) and Ryan Presley (Marri Ngarr/ Scandinavian), work alongside locally based artists for a series of residences in Ceduna and Adelaide between January and September 2019.

Travellers who have visited Arts Ceduna and been privileged to meet artists and hear them talk about their work will have a clear understanding of how central the region is to a fundamental sense of identity and belonging. Creation accounts are centered on the Bunda Cliffs, which form part of the longest stretch of cliffs in the world. The collective mood of works by No Black Seas artists is sombre and grounded. Affirmative, visually mesmerising images associated with Arts Ceduna artists’ paintings are on this occasion set aside as a fresh cohort of activist-artists is launched into the world. They must feel that they are living in a parallel universe. The dominant message of Fight for the Bight–type campaigns and protests is that the risks to the natural environment are far too high. Somewhere within this, and despite Mirning elder Bunna Lawrie’s presence in a Bight Alliance delegation to Oslo this year, the voices of Indigenous people, the message that this place is their cultural heartland, is being buried in the rhetoric.

As one artist, Collette Gray, explains, once the whales are gone and the area destroyed “my children will have no culture”. “I don’t want to move from here,” says another No Black Seas artist Yana Tschuna. “This is where my grandmother is from, and her mother, and her mother, and her mother …” This is a green shoots project that has taken regional artists well out of their comfort zones – such as Beaver Lennon applying symbolic designs to surf boards. Its structured process, involving extensive consultation, workshops and the guidance of experienced artists (Yhonnie Scarce and Ryan Presley), plus a disciplined ACE Open space hang, gives the concerns of remote and vulnerable South Australians a much-needed voice and invites others to see the bigger picture and get on board. As for No Black Seas’ visual credentials, look no further than Collette Gray’s striking Bunda cliffs mural and an installation of sand-cast glass sculptures referencing marine life drowning in oil.

As Dan Graham says, “more real than art”.

John Neylon is an award-winning art critic and the author of several books on South Australian artists including Hans Heysen: Into The Light (2004), Aldo Iacobelli: I love painting (2006), and Robert Hannaford: Natural Eye (2007).