Walter Marsh

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

From ‘Blackbirding’ to 40,000-year-old petroglyphs, a new project from artists James Tylor and Matt Chun hopes to provide an accessible starting point for those wishing to dive into the deeper histories of this continent.

“I think that people just don’t know – I think they’re coming more from a sense of being disempowered through being unaware, rather than from a callous point of view,” Tylor tells The Adelaide Review. “You’re not really ‘relearning’ these histories… you were just never told them in the first place.”

It was Scott Morrison’s since-recanted comments that “there was no slavery in Australia” in June that prompted Tylor, a Kaurna, Māori and European artist and researcher and 2017 Ramsey Art Prize finalist, to float a new project with regular collaborator Chun.

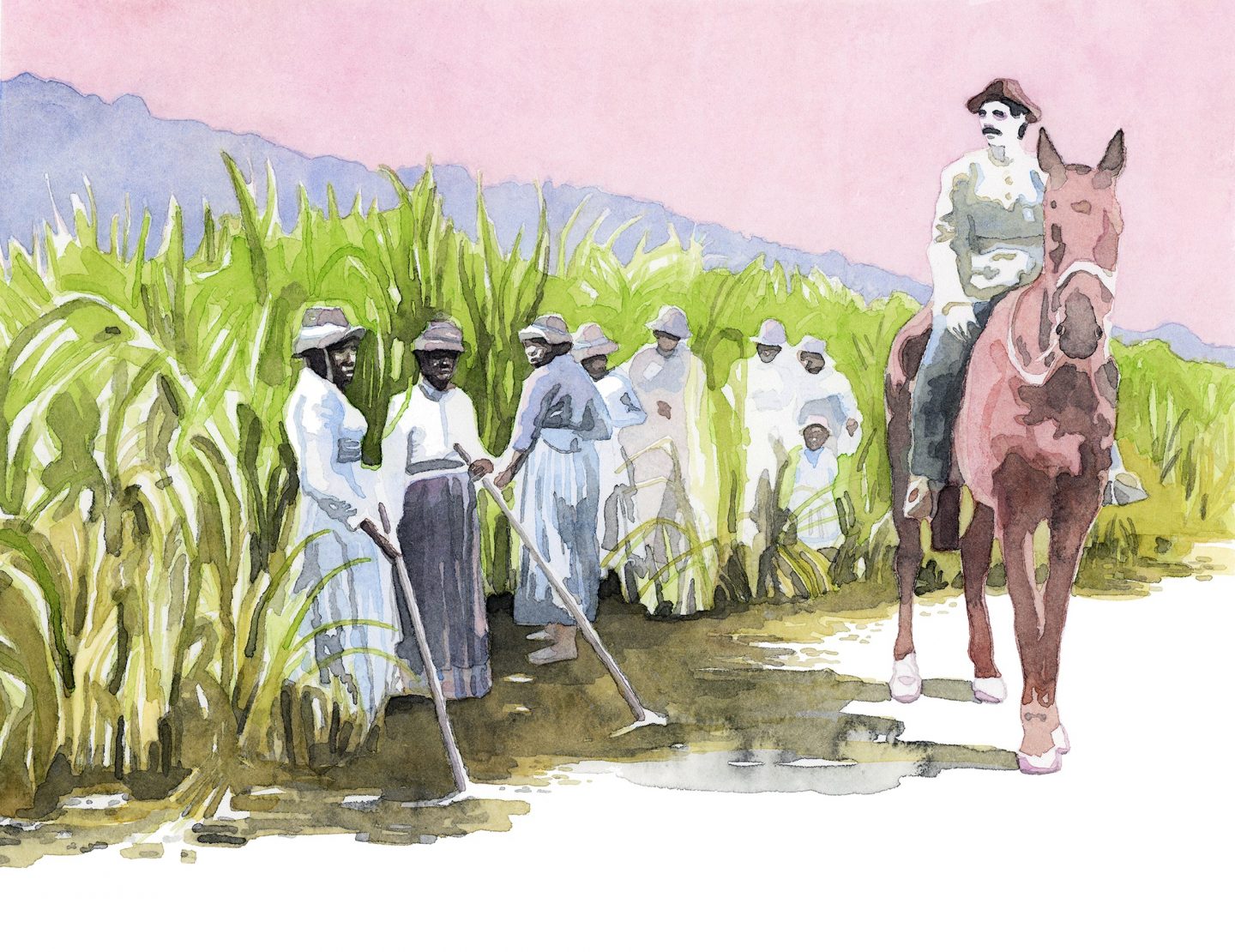

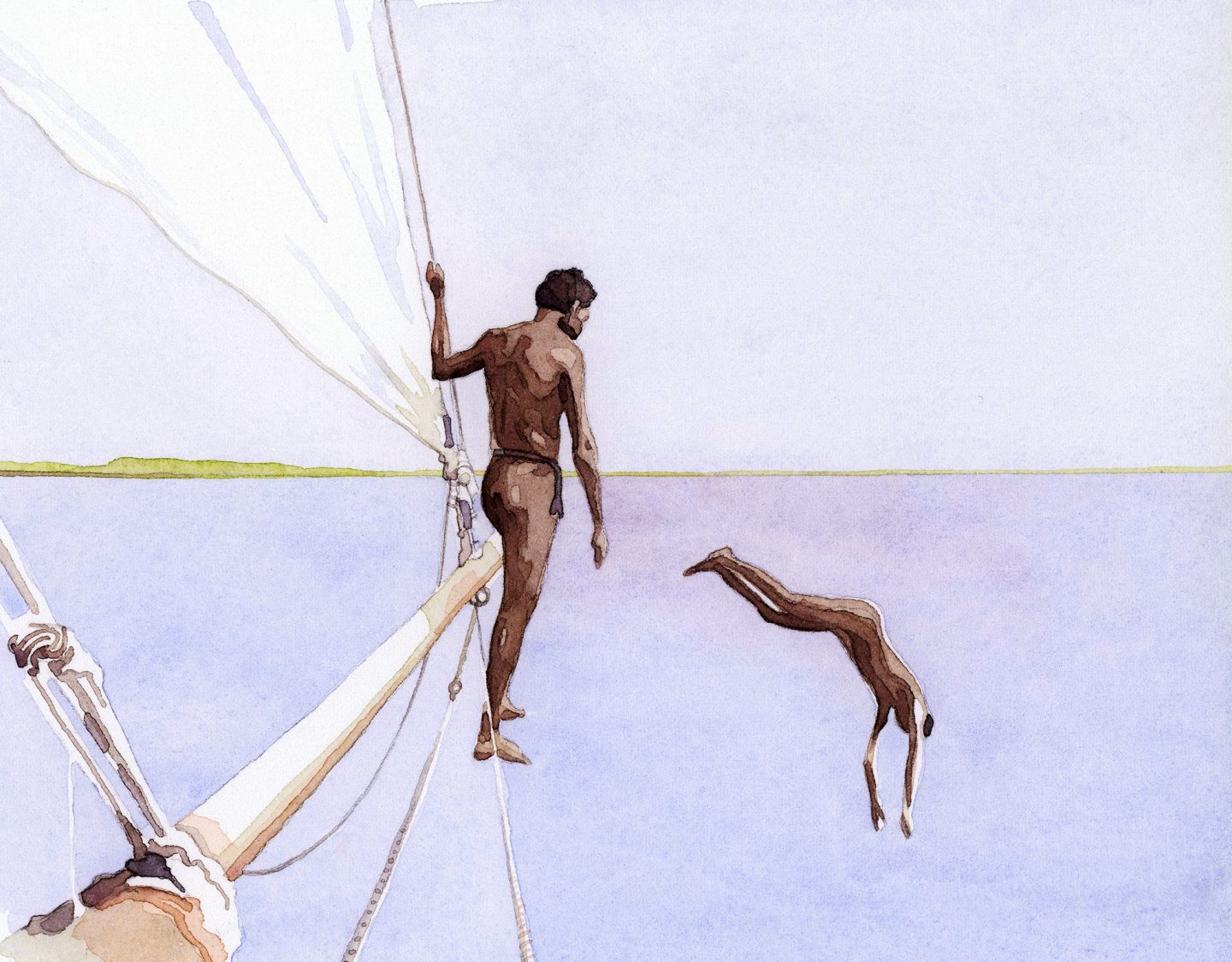

Within a fortnight the pair had started the @un_monumental Instagram handle, posting weekly about slavery in Australia’s 19th century pearling industry, pre-European trade networks between Makassan seafarers and Aboriginal nations, and ‘Blackbirding’ in the sugar cane industry. As Black Lives Matter protests inspire renewed interest in Australia’s colonial legacies and pre-settler past, Tylor says their goal was “to place the facts so people can just see it, clean and cold”.

“I just said to Matt, ‘we should do something about Australian history with watercolours – you do the watercolours and I’ll do the text’,” he explains. “We wanted to start around the theme of Black slavery around Australia, which Scott Morrison said didn’t happen, but it’s affected over 10 communities within Australia: the Indigenous community, the Chinese Malay population on Christmas Island, South Sea Islanders in the cane fields of Queensland. Aboriginal people have been basically subjected to slavery ever since colonisation, whether it’s domestic servitude or being unpaid farmhands just for rations – it’s all those sorts of things that have never been labelled.

“If they were to be done today they would totally be forms of slavery; if you look at the British parliamentary papers of the colonisation of South Australia, they essentially lift the exact definition, without saying ‘slavery’, for the terms of Kaurna people on the Pirlta wardli mission – where the nine-hole golf course is now, just down by the River Torrens. Food and lodgings, that was the only payment, but the work they had to do had to be greater than food and lodgings… which is essentially slavery. And that was under the South Australian government, not private hands.

“It’s affected so many communities, so I just wanted to say something about it, and have content that could be easily shared across social media as well.”

In offering simple, clearly referenced information accompanied by shareable, Instagram-friendly illustrations, the project is part of a growing volume of First Nations artists and activists embracing social media to inform, organise and inspire solidarity in non-Indigenous audiences.

“What’s really hard about Australian history is there’s not much imagery to follow up many historical events,” Tylor says. “So this was a great opportunity to lock onto a subject, and then write about it very simply, in a way that people can easily digest.

“We put all the resources that we’ve taken the information from on a website, so people can go and fact check it if they want to. Australian history is everyone’s history – this is our representation of facts in a way that’s digestible, [but] it’s all there if people want to do further research.”

“Half of what happened probably wasn’t recorded anyway; what we’re grabbing hold of in this [project] is a very censored version of history – not by us, but people just didn’t record it.”

While much of the information shared by Un Monumental comes from publicly available resources often published on government websites, Tylor says this ‘official’ historical record – often left deliberately opaque by settlers – offers only a fraction of the full story.

“Half of what happened probably wasn’t recorded anyway; what we’re grabbing hold of in this [project] is a very censored version of history – not by us, but people just didn’t record it,” he explains, referencing an inevitably large volume of frontier violence that surfaces only in euphemism or inadvertent disclosures.

“A lot of those histories just weren’t recorded, so you’d never be able to find that content these days unless you get it from oral histories,” he says. “Which you can get; my non-Indigenous family have had oral histories passed down which line up with Indigenous narratives that were recorded, communities that have the exact same stories as well. You can piece it together that way, but you have to find people who will share it – you can’t just take it off a shelf.”

And, while South Australia is gradually becoming more aware that beneath the long-held veneer ‘free settlement’ lies its own troubling, and unresolved history of violence and dispossession, the often-fierce debates that have divided towns like Elliston suggest many may not be ready to confront the frontier bloodshed linked to well-known names like Hawker, Frome and O’Halloran.

“All of these people have places named after them and did atrocious things,” he says. “And we’ll write about that stuff as well. There are some really interesting things we want to cover, like the Port Lincoln wars – the Barngarla nearly won against the British at the height of the British Empire,” he says of sustained resistance in the early 1840s that saw the colonial government send military reinforcements. “They nearly abandoned Port Lincoln, and that’s pretty amazing for South Australia’s history alone.”

Shedding greater light on frontier conflict is an important part of Un Monumental, but so is recognising that the last two centuries are a small, particularly turbulent footnote in the millennia of human history on this continent. As the destruction of Juukan Gorge and Djab Wurrung birthing trees demonstrates, this is often given less weight than more recent forms of heritage.

“We’re looking at this idea of colonialism because it’s topical at the moment, but we will flip it and go back to pre-colonial history, things that are tens of thousands of years old. Like the first mine in the world in far west New South Wales, or the oldest stone structure in the world in Arnhem Land.

“We want to make people aware that that history exists as well, but we’re going to do a lot of consultation with traditional owners first – we want that consultation to be really considerate and not rushed.”

In using art to fill out gaps in the more widely-held colonial narratives, the project echoes the spirit of Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones’ Tarnanthi 2019 exhibition Bunha-bunhanga, which reinterpreted colonial landscape paintings and Aboriginal objects to illustrate the research of Bruce Pascoe, Bill Gammage and Zena Cumpston.

“It’s interesting because the vast amount of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu, and Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate On Earth looks across the nation, but is quite focussed on the east coast. But we have the same content in Adelaide; there’s records of the exact same things [Gammage and Pascoe] are talking about happening in Norwood. The information is there, but I think it’s harder in Australia to piece the pieces together because the narrative has been so interrupted.

“So it’s about getting all the important resources and putting them in one place – so people can work their way back out.”

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.