John Neylon

John Neylon is an award-winning art critic and the author of several books on South Australian artists including Hans Heysen: Into The Light (2004), Aldo Iacobelli: I love painting (2006), and Robert Hannaford: Natural Eye (2007).

Somewhere between romanticised fiction and historical truth, the samurai have managed to make an impression well beyond Japan that endures today.

Everyone has a samurai moment when something – a film, TV show or comic – created an indelible image of what a samurai warrior should look like and get up to. Mine was Shintaro, that mid-1960s TV series The Samurai that enjoyed local popularity and, incidentally, was the first Japanese TV program to be screened in Australia.

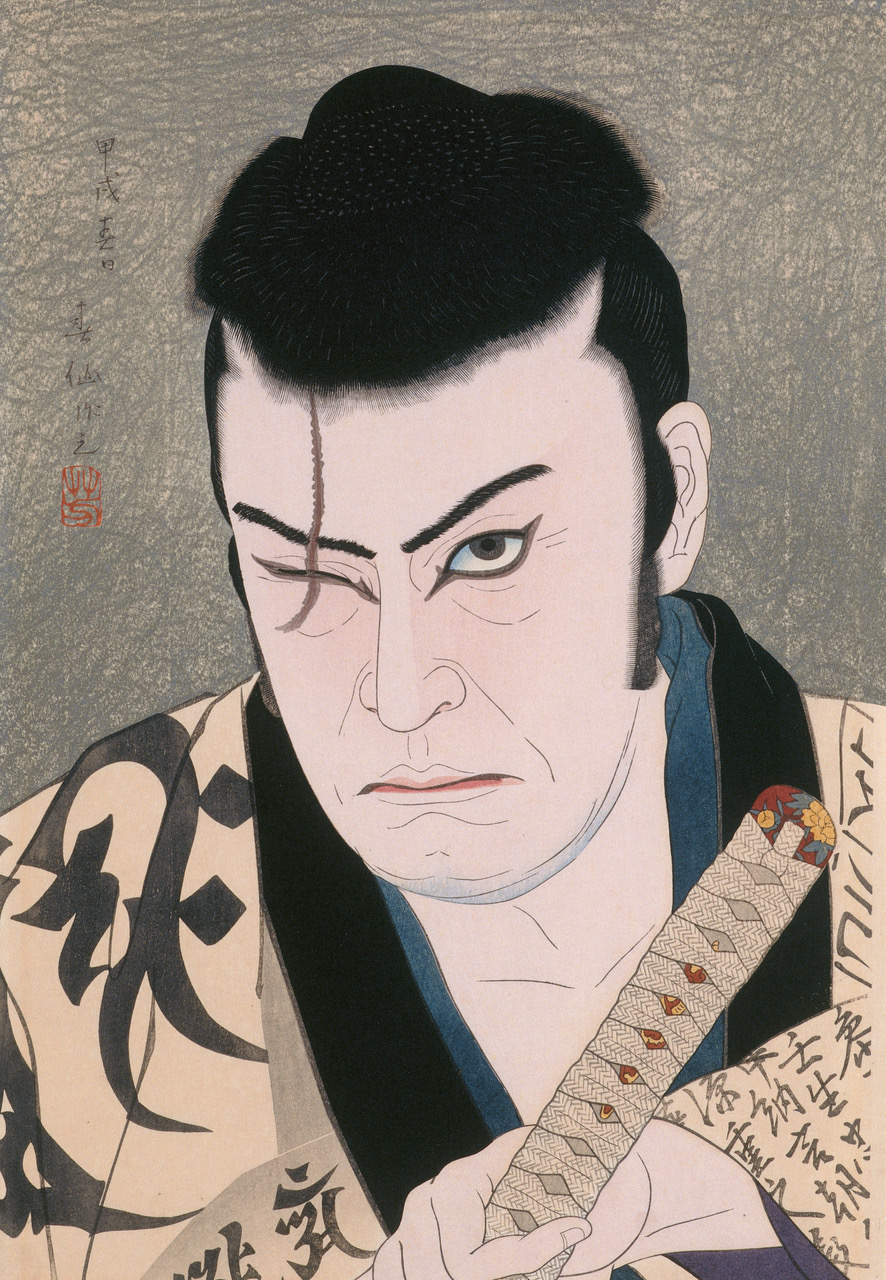

There are nods to samurai popism in this exhibition. A woodblock print by Shunsen Natori, for example, depicts 1930s actor Okichi Denjiro as the fabled one-eyed, one-armed swordsman Tange Sazen. Here’s a guy you don’t mess with.

Samurai can be experienced as a journey that starts in feudal Japan, as seen through the prism of art and artefacts that reflect evolving social and cultural change into the 20th century. Or it can be adopted as a vantage point from which to view the legacy of samurai-centric culture within contemporary Japan, and, indeed, the global community. This tension between historical truth and romanticised fiction gives Samurai, the exhibition, a strong shot of adrenalin.

While in the tradition of reflective haiku poetry , moons waning, leaves falling, hands that once held tea bowls or swords turned to dust, the charisma that surrounds these artefacts – screens, armour, weaponry, prints and ceramics – speaks to a contemporary imagination.

To test this response, start with one work, Tenmyouya Hisashi’s Conquest of the Karasu Tengu, from the series One hundred new ghost stories. This is a wildride image depicting a hero fi ghting crowfeatured Karasu Tengu. Samurai curator Russell Kelty’s catalogue interview with the artist opens a doorway to looking at not only Tenmyouya’s practice but its roots in street culture, and anti-social subculture, particularly kabukimono (‘the crazy ones’) extending back to the 16th century.

Kabukimono were either ronin (outlaws) or members of street gangs that were known for transgressive, outrageous behaviour and adopting flamboyant appearance s in clothing, hairstyle and weapons.

Tenmyouya, in developing his theory, BASARA, which legitimised kabukimono as contributing to modern day Japanese culture, also saw a connection with forms of art which expressed an ‘untamed, flamboyant attitude’, described at other times as ‘eccentric’. Even the counter–culture of bosozoku (1980s to 1990s biker gangs) Tenmyouya saw as embodying the brash qualities of the anti-social samurai.

Between Tenmyouya Hisashi and the ukiyo-e woodcut prints in Samurai is a small step in terms of seeing obsession with the samurai as an expression of working class nostalgia for the days for yore and gore, as well as dissatisfaction with authority. The prints of Utagawa Kuniyoshi in particular, and others, cast samurai warriors as superheroes. Look for his dynamic capture of youthful hero Sasai Kyuzo Masayasu’s final moments as he charges into a volley of gunfire. The classic epic, The revenge of the forty-seven ronin, as envisaged by Hasegawa Sadanobu II and Kuniyoshi’s prints of individual members of the group are points of reference to mid- 19th century debate about traditional samurai values (such as loyalty and avenging one’s master) being in conflict with modern, legislative systems of justice.

The samurai were not a unified class. Some had positions of authority and privilege within the 300 daimyo houses that administered the regions of a unified archipelago in the Edo Period (1603–1868). The cultural tastes of this upper elite differed from lower classes in preferring refinement over sensationalism. The sense of order and calm that defines the overall exhibition experience is driven by the many items that reflect the quality of the Gallery’s collection, bolstered in recent years by significant benefaction.

The painted screens and scrolls in particular derive much of their aesthetic qualities from systems and rituals of discipline and those associated with Zen Buddhism. It also denotes the ideals promoted by the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa that celebrated an aesthetic language in which the terms wabi (simple and unpretentious beauty), sabi (natural patterning and ageing/ beauty of poverty) and yugen (profound grace and subtlety) were prominent. Such qualities are to be found in the austere beauty of items as diverse as a Kano school 17th century screen (Birds, tree and flowers), the magnificent scroll paintings, tsuba (sword hand guards) and the selection of tea bowls.

These last items are capable of taking the viewer to the heart of a particular mindset that values exchange between a rustic, slightly imperfect object and deep emotions that come from reflection on life as transient but transcendent.

Perhaps having spent time with this exhibition (supported by incisive critical essays within the AGSA catalogue), a more informed understanding of the roles of the samurai as a touchstone of tradition but also agents of change will emerge. Kelty’s catalogue interview with Tenmyouya Hisashi and survey of the samurai in the modern world, and Ryan Holmberg’s survey of the samurai in postwar visual culture recast the samurai as a portal into a contemporary parallel universe where elite and popular culture, even beauty and violence, coexist in ways that defy conventional imagination.

John Neylon is an award-winning art critic and the author of several books on South Australian artists including Hans Heysen: Into The Light (2004), Aldo Iacobelli: I love painting (2006), and Robert Hannaford: Natural Eye (2007).