Difficult pleasure: Brett Whiteley Drawings

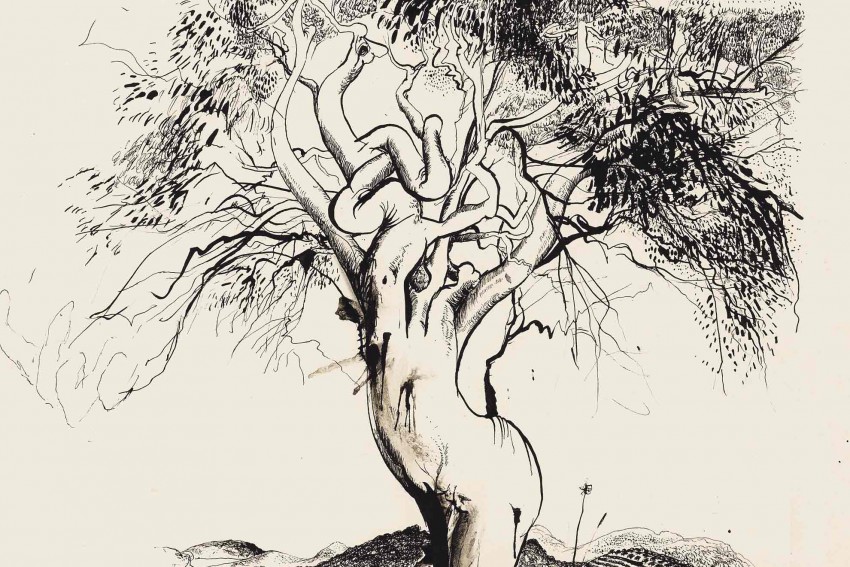

Brett Whiteley Drawings, Lou Klepac

Brett Whiteley once wrote to his father with the absolutism of youth, “The only thing that’s SHAREABLE is the realisation of the loneliness of one’s destiny”. He was wrong. His art always communicated a hunger for life and beauty. From personal observation, Whiteley no longer seems to be on the radar of emerging contemporary artists or audiences. He used to be talked about a lot. Now he doesn’t – except when fraud cases and the like bob up in the media. Perhaps the passing of time has dulled the public imagination to his extraordinary talents. Some polishing is overdue and Lou Klepac’s new book on Whiteley’s drawings is well up to the task. Whiteley burst onto the art scene half a century ago, in the early 1960s, surfing a breaking wave of British enthusiasm and curiosity about contemporary Australian art. Aged 21 years he had three of his paintings acquired by the Tate Gallery, the youngest artist to have been bought by this institution. Robert Hughes’s ground-breaking The Art of Australia was first published in 1966 with an image from Whiteley’s Christie series on the cover. Whiteley had met Francis Bacon in London in 1962. This experience fuelled Whiteley’s obsessive curiosity about the louche underbelly of London society and the infamous Christie murders in particular. The paintings and drawings of this series communicate, to this day, a sense of brutal dismemberment, overlaid with sexual fantasy and underpinned by forensic morbidity. Sex and carnality remain powerful attractors within the artist’s oeuvre but never as dark or morally compelling as in this series. It is worth noting that Matisse, whom Whiteley admired, once said, “In the morning to begin the day well I have to feel like killing someone; I must have things to give, energy to expend.” “Energy to expend” in Whiteley terms is code for ‘controlled explosion’. He characteristically attacked the white spaces of drawing sheets and canvases with intense concentration and take-no-prisoners gestures of brush, pencil of charcoal stick. When it came to articulating how or why this happened Whiteley speaks with compelling eloquence. “Everything is in a state of flux, everything seems to be gyrating out from an invisible point of silence, all movements, motions, actions seem circular, an endless and inexplicably beautiful system rotating around the terror of nothing.” The critical factor in engaging with Whiteley’s work, and the drawings in particular, is to respond to his passion and talent for mark making. This is a relatively old-fashioned concept these days. Generally speaking, younger artists use drawings to articulate or describe things. As a love child of the AbEx era, Whiteley subscribed to the idea of gesture as an expression of an inner truth. But this did not mean indulgent excess. As he explained, “One of the hardest things is to discipline oneself until one sees to a point of almost insistent madness, to concentrate on one vision until it discloses its third or fourth veil, to keep seeing past what you have just seen requires feeling and ambition.” This mark making imperative is front and centre in Klepac’s book. The numerous, high quality plates track a lifetime’s subscription to the act of drawing as an end in itself. As the accessible and scholarly text illustrates, Whiteley was no kamikaze wunderkind but a dedicated artist who paid his dues, studying at first not only the work of moderns and contemporaries such as Bacon, Matisse, Picasso, Gorky and others but European masters such as Italian old masters including Piero della Francesca, Masaccio and others. Klepac draws particular attention to the role played by the work of the artist William Scott in framing Whiteley’s engagement with contemporary European art and evaluates Whiteley’s body of drawing within a wider European studio tradition. Barry Pearce interviewed Michael Johnson in 1994 about his formative associations with Whiteley. These lively recollections, included in the book, shoe-horn the reader into another time, when becoming an artist and being a young Australian artist overseas came on like a runaway train. Australian landscapes and the trees that emerged as subjects within Whiteley’s work following his return to Sydney from Europe in 1965 became anthropomorphised to resemble sinuous torsos. This inflection creates an intriguing sense of tension and hybridity in a diversity of landscape subject drawings made around Sydney and the Glasshouse Mountains as well as on European travels. From the 1970s, Whiteley became increasingly interested in Oriental art and calligraphy, particularly brushwork. The result was a visual grammar of sinuous lifework, charged spaces and velvety blacks the French Symbolist artist Odilon Redon might have envied. Adding poignancy and candid insight into the drawings are selected pages from the artist’s notebooks in which he drew, and wrote his reflections on art, painting and drawing. This handsome publication is the richer and edgier for their inclusion. Brett Whiteley Drawings, Lou Klepac, The Beagle Press, Sydney Image: Tree, Tuscany / ‘The gum tree at Mangrove Mountain’ (detail), c.1980, pen and ink 43 x 48 cm, private collection. Copyright Wendy Whiteley.