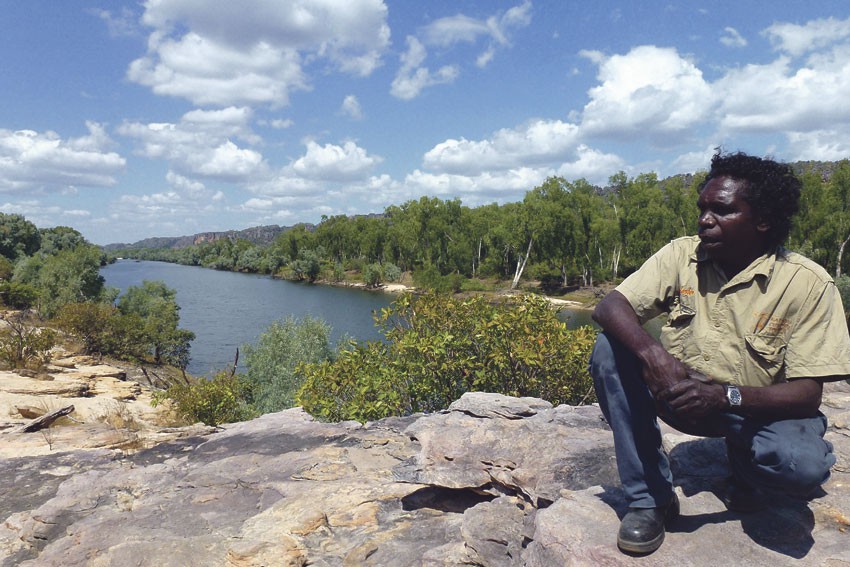

Kakadu Dreaming

Kakadu is a place of gods and giants where the land’s most powerful ancestor has been nature’s most precious resource.

At the heart of Northern Territory’s Kakadu National Park rests Nourlangie, an enormous sandstone plateau that rears abruptly out of the surrounding woodlands. This is Kakadu’s stone country and it is plain to see why a thousand generations of Indigenous people have seen the hands of powerful ancestors in the formation of this land. Here the land is a storyteller; the rocks sing songs of ancient tides, the animals tell tales of coming seasons.

The stone country is a place of great change, great diversity and great challenge. Yet, in a landscape almost half as old as the world itself, there remains one constant: when it comes to history it is water that has set the course. To the local Gun-djeihmi speakers the area is known by two names; Anbangbang for the scrubby bushland that encircles the great rock, which is itself known as Burrunggui. For 20,000 years the nomadic people of the Kakadu region sought shelter here. Hiding from the summer’s torrential rains these people impressed their histories and their stories onto the rock across several exquisitely preserved rock-art galleries.

Because of this, Anbangbang and Burrunggui are now as central to the bus and campervan tourist trail as these paintings were to the everyday lives of the local Aboriginal nations. Yet even in Kakadu’s high season it only takes one step off the well-beaten path to feel like the only person in the park.

Sheering off from the trail at the base of Burrunggui is the Barrk sandstone bushwalk; a rugged 12km hike over and around great plateau. As the track heads sharply up towards the baking sun, you’ll probably begin to appreciate water’s most immediate function for life and just how important it must have been in a landscape where water did not come from a tap or came packaged in bottles.

Over rockfalls and up dry creek beds, you’ll be flanked on either side by Burrunggui’s towering, golden red cliffs as you climb. When the track finally crests onto the plateau you can look back for stunning views over Kakadu’s mottled green bushland. Cast your gaze back 120 million years ago and all below you would have been water, when Burrunggui was an island in a shallow sea that both formed and eroded much of Kakadu’s landscape into what it is today.

From the Burrunggui plateau you can also see Kakadu’s great escarpment, which would once have been sheer sea cliffs, now rising up to 330 metres above the plains. Beyond lies Arnhem Land. At this very edge of Kakadu you can see the sacred Namarrgon djadjam, or Lightning Dreaming. Guarded by what look like three pillars carved into the escarpment, Lightning Dreaming is the home of Namarrgon, the Lightning Man.

Every year in late October Namarrgon emerges from his home atop the escarpment, bringing the thunder and the lightning that herald the turning of the seasons and the coming of the wet. Portrayed with lightning in both hands and axes on his elbows and knees, Namarrgon rolls across the sky cleaving trees with his axes whenever he strikes the ground.

With the rains come rejuvenation and the next stage in a seasonal cycle that has remained unchanged for over 8000 years. Kakadu explodes in life and the whole country replenishes the stores that will see it through the reciprocal dry season. The Barrk trail then continues out across the Burrunggui plateau, through the many faces of Kakadu’s stone country. Here you can see how quickly water – or more importantly the absence of it – changes the land.

Through only a few kilometres you’ll experience lush gullies and stone cuttings that have been laboriously carved by the coursing waters of the wet, through sheltered monsoon forests, across exposed rocky moonscapes and then finally back down Burrunggui’s other side into into the tinder-dry woodlands where the bent, yellowed spear grass stand as the year’s first casualties of the dry.

As the sun goes down, the place to be is the nearby Nawurlandja lookout, watching the sunset drip off the cliffs of Burrunggui. An imposing sandstone slab, Nawurlandja was most likely formed as the bedrock of a long-lost ocean and has since been sculpted by thousands of years of rain scouring down its slope to the Anbangbang billabong at its foot.

And it is in billabongs such as Anbangbang that water once again translates into life. Over the coming months the creatures of this lagoon – the iconic crocodiles, the careful-footed egrets and brilliant kingfishers – will live out another year’s cycle in this shrinking body of water.

Change may be inevitable but in this magical place change is the only way that all things can remain the same.

Image:Photo: Carol Cotterill