Walter Marsh

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

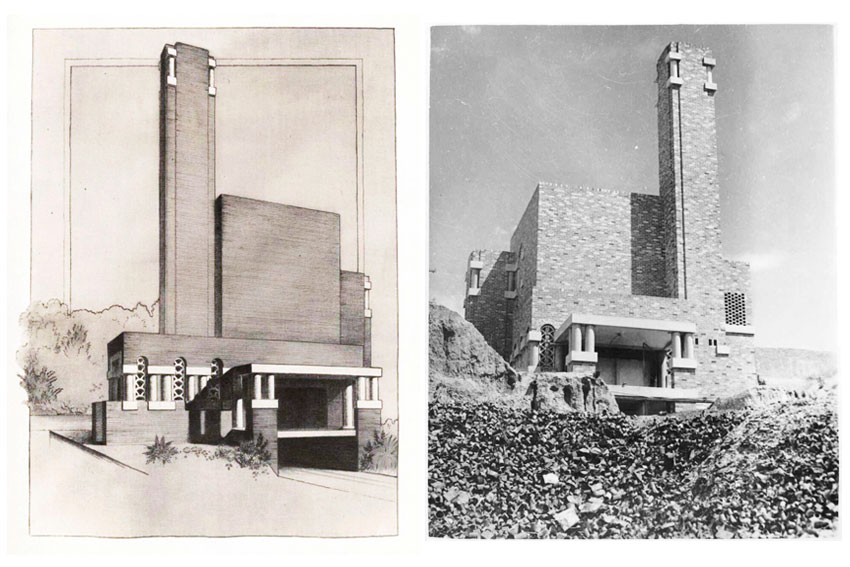

Having famously laid out the nation’s capital, American architect Walter Burley Griffin spent his final years bringing a bold aesthetic vision to a most unedifying subject: burning waste. Now, the former Thebarton Reverberatory Incinerator is cooking up fire tracks in its new life as a recording studio.

Driving down West Thebarton Road a keen eye might notice the angular red smoke stack poking up from the industrial lots and car parks, its sharp lines and polychromatic brickwork resembling something out of Minecraft. It’s one of several architecturally significant ‘reverberatory incinerators’ around Australia that Griffin and colleague Eric Milton Nicholls designed during the Great Depression. When it opened in March 1936, less than a year before Griffin’s death, newspaper reports welcomed the influence of “modern architecture” on Thebarton’s “imposing” new addition.

Today it’s home to Lewis Wundenberg, an Adelaide engineer and producer who has spent years training his ears to avoid ‘rubbish’. But when the city studio he worked at went under, leaving him at a loose end with more recording gear than he could fit at home, this “really weird” online listing caught his eye.

A sophisticated bit of waste solution for its time, this generation of reverberatory incinerator could process 15 cubic metres of garbage a day, without its operator touching a single piece of waste. Refuse would be dropped by truck into the structure, whose furnace could exceed 1000 degrees Celsius, nearly three times the maximum reached by older styles of furnace. Such extreme heat also served to neutralise odour and smoke, while energy from the burning was also used to heat bitumen for council roadmaking.

Such trash-burning might sit uncomfortably with today’s sensitivities to airborne pollution, but represented a vast improvement from the previous system of tipping household refuse into ‘pug holes’ around the suburbs, a practice deemed ‘unsanitary and unsatisfactory’. “Apparently they had a massive rat problem,” Wundenberg says.

After being decommissioned in the 1960s, the site around the incinerator was used by council workers for a number of years, before a previous tenant converted the bottom furnace level into a recording studio. Since answering that Gumtree ad last year, Wundenberg has expanded with a second studio in the upper levels of the incinerator, and rehearsal rooms located in an adjacent building.

The building itself isn’t the only piece of history at play in Wundenberg’s studio, which features pieces of once-prized analogue equipment rescued from liquidators, retiring producers and demolished TV studios. “This mixing desk is a Neve,” Wundenberg explains in a venerating tone. “Apparently the BBC commissioned it – these things were like the Rolls Royce of mixing desks, and you could custom configure everything to your needs. Billy Thorpe bought it somewhere along the way and had it at his home studio for years.”

A key addition to the second studio is a custom-made soundproof vocal booth salvaged from Channel Nine’s now-demolished North Adelaide studios, complete with autographs from presenters like Jane Doyle and Catriona Rowntree scrawled on its doors. A former lecturer of Wundenberg’s worked at the studio, and passed the booth onto his former student when he couldn’t find a home for it – provided Wundenberg could move the structure.

“Getting it through that door was an absolute nightmare,” he says, adding that despite being designed for easy transportation, its weighty components, and the removal of the original access ramp once used to deposit refuse into the same chamber, proved a logistical challenge.

Cheap consumer software has made home recording more accessible than ever, but there’s one thing digital plugins can’t recreate for bedroom producers: peace, quiet and zero neighbours. And as former industrial areas on the city’s fringe are reclaimed and redeveloped for residential use, Thebarton is becoming an increasingly important playground for Adelaide’s music scene. Wundenberg’s isn’t alone – a converted mechanics’ garage just down the road has also served as a recording and rehearsal studio for years.

“It’s so close to the city, but it’s so industrial,” Wundenberg says of the location. “I could have guitar amplifiers blasting at five in the morning and it doesn’t bother anyone. The hardest thing is finding somewhere where you can set up and make noise, and not affect or annoy the neighbours,” he says of the challenges of finding appropriate studio space.

“That’s why I’m really lucky here. The walls are so thick – it was an incinerator!” he marvels. “It’s the ideal situation.”

It’s not uncommon for heritage structures to find a second life; older buildings are turning into bars, homes, live music venues and coworking spaces. But there aren’t many business models for which an air-tight, windowless, thick walled building with zero foot traffic is actually an advantage, making the work of Griffin and Wundenberg a dream pairing. 83 years after its completion, this garbage fire is now a sound example of recycling.

Wundenberg’s Recording Studios

West Thebarton Road, Thebarton

wundenbergs.com

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.