Castro’s Award

After winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973, Patrick White used his prize money to fund the Patrick White Award, this year’s winner is Brian Castro.

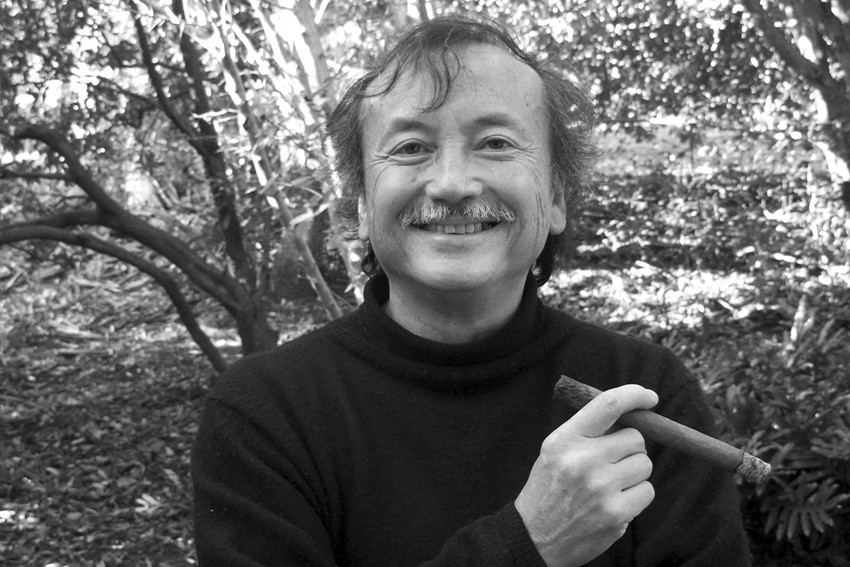

After winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973, Patrick White used his prize money to fund the Patrick White Award, which rewards writers who have produced exemplary work over a long period of time. This year’s winner is Brian Castro. Castro has received numerous literary prizes over the past two decades and fellow writers hold his work in high regard, but Castro’s novels rarely reach a wide audience. This is partly due to the misconception, proliferated by a small group of influential critics, that his fiction is superficially ‘clever’ or wilfully obscure. Born in Hong Kong in 1950, Castro was very young when his father decided to send his children to boarding school in Australia. He says, “My mother was bereft because here was her daughter, who was 11, and her son, who was 10, being sent thousands of miles away, with no support.” When his mother came to visit them seven years later, “she was totally estranged from us… we were like strangers.” As a teenager, Castro embraced a typically Australian way of life. “I was into hotted up cars. I had many motorcycles and fell off a lot of them. In the holidays, friends from boarding school invited me to stay on their farms, which were big properties in the Northern Territory and northern New South Wales, and I’d go out there and learn to ride horses and shear sheep.”  Brian Castro. Photo Jennifer Rutherford But this easygoing lifestyle was shaken by political events in the late 1960s. “When I was 18, I got the notice to be drafted for Vietnam, and that turned me around intellectually. I couldn’t get a Commonwealth Scholarship because only full Australian citizens could be awarded one, yet I could be conscripted to die for Australia, as a British subject, because the Commonwealth was fighting in Vietnam. That use of double-terminology, and institutional hypocrisy, had a deep effect and it probably shaped a lot of my writing. “After that I was hostile to the kind of naïve nationalism that a lot of Australian writers embraced at the time – a kind of uncouth ocker sensibility – which didn’t represent the Australia that I’d experienced or the people I knew.” The result of Castro’s rejection of popular representations of Australian identity has been a sophisticated form of narrative, deploying a vast range of moods and styles, voices and cultures. In essays, Castro offers clues about his particular approach to writing, his literary obsessions and moral concerns. In ‘Arrivals’ he writes of “being transported mapless into that adventurous, though seaworthy boat called the novel, in which the extremities and the ambiguities of prose have always provided the greatest mutabilities”. Each of his novels to date is rich in textual play, demandingly intelligent and emotionally expansive, ranging from slapstick comedy and bawdy humour to deep melancholy. Castro explains, “I learnt that from Shakespeare. Shakespeare was a ‘real man’, in that he lived among the hoi polloi, and he addresses everyone and everything in his plays.” But Castro is also aware that this kind of fulsome literature is endangered. “What we seem to have lost is the art of difficulty and complexity. In fact, anyone can engage with complex material if they choose to. It isn’t just for academics or university graduates. Any person in society who reads and who is a sensitive reader can understand what’s going on in my books. What I’m playing at a lot of the time is mocking this idea that only ‘great intellects’ can pierce through and decipher what the ‘great work’ is.” With his most recent novel, Street to Street (2012), Castro demonstrates a subtler, more compressed kind of literary mastery. It was his first ‘Adelaide novel’, written in the city where he occupies the University of Adelaide’s Chair in Creative Writing, and it’s certainly one of the finest novels produced here. He says of the city, “It’s a quiet place where you can write. Why did Philip Hughes come here? To settle down and concentrate on cricket. This is what you do in Adelaide, whether you’re a sportsman or a writer: you settle yourself.” Castro seems to have settled very well. In late 2014 he read from a work in progress, a verse novel titled Blindness and Rage. More awards will surely follow. briancastro.com.au Brian Castro photo: Annette Willis – annettewillis.com

Brian Castro. Photo Jennifer Rutherford But this easygoing lifestyle was shaken by political events in the late 1960s. “When I was 18, I got the notice to be drafted for Vietnam, and that turned me around intellectually. I couldn’t get a Commonwealth Scholarship because only full Australian citizens could be awarded one, yet I could be conscripted to die for Australia, as a British subject, because the Commonwealth was fighting in Vietnam. That use of double-terminology, and institutional hypocrisy, had a deep effect and it probably shaped a lot of my writing. “After that I was hostile to the kind of naïve nationalism that a lot of Australian writers embraced at the time – a kind of uncouth ocker sensibility – which didn’t represent the Australia that I’d experienced or the people I knew.” The result of Castro’s rejection of popular representations of Australian identity has been a sophisticated form of narrative, deploying a vast range of moods and styles, voices and cultures. In essays, Castro offers clues about his particular approach to writing, his literary obsessions and moral concerns. In ‘Arrivals’ he writes of “being transported mapless into that adventurous, though seaworthy boat called the novel, in which the extremities and the ambiguities of prose have always provided the greatest mutabilities”. Each of his novels to date is rich in textual play, demandingly intelligent and emotionally expansive, ranging from slapstick comedy and bawdy humour to deep melancholy. Castro explains, “I learnt that from Shakespeare. Shakespeare was a ‘real man’, in that he lived among the hoi polloi, and he addresses everyone and everything in his plays.” But Castro is also aware that this kind of fulsome literature is endangered. “What we seem to have lost is the art of difficulty and complexity. In fact, anyone can engage with complex material if they choose to. It isn’t just for academics or university graduates. Any person in society who reads and who is a sensitive reader can understand what’s going on in my books. What I’m playing at a lot of the time is mocking this idea that only ‘great intellects’ can pierce through and decipher what the ‘great work’ is.” With his most recent novel, Street to Street (2012), Castro demonstrates a subtler, more compressed kind of literary mastery. It was his first ‘Adelaide novel’, written in the city where he occupies the University of Adelaide’s Chair in Creative Writing, and it’s certainly one of the finest novels produced here. He says of the city, “It’s a quiet place where you can write. Why did Philip Hughes come here? To settle down and concentrate on cricket. This is what you do in Adelaide, whether you’re a sportsman or a writer: you settle yourself.” Castro seems to have settled very well. In late 2014 he read from a work in progress, a verse novel titled Blindness and Rage. More awards will surely follow. briancastro.com.au Brian Castro photo: Annette Willis – annettewillis.com