The Bones

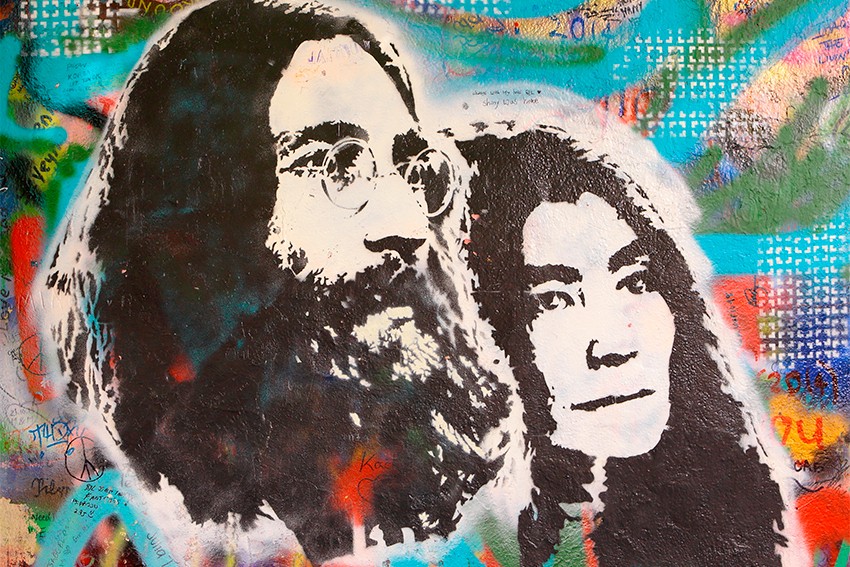

Each day we become smarter, yet less willing to use our intelligence, writes Stephen Orr.

WG Sebald describes the scene: a cliff collapsing into the ocean. Above, a churchyard. As people watch, coffins fall into the sea, bones flying through the air. Even in death, after mouldering centuries, there’s no privacy. Extend the scene. Homes are next, walls collapse, bedrooms exposed to a gaping crowd. Wardrobes fall, clothes and shoes tumble towards the surf. And under H’s bed, a girl. Blown up, perhaps, or maybe a plastic number? Everyone gasps and looks at H. He turns away. Is this the world we’re entering? Where everything, no matter how private (or well-hidden), will be on display. Is someone plotting to undermine our lives, or does it just happen this way? Can H continue living in his town, given the shame? Was he really hurting anyone? And does it matter to the onlookers? Every day a little death (of the self). Parts dropping off. At work, where we shouldn’t take more than three minutes in the toilet; the street, where a thousand closed-circuit eyes are always watching; social media, where our images and thoughts are hijacked, paraphrased, sold to corporations, misunderstood, bitched about. None of us can say where this began, because it’s happened so gradually. Now, it seems, we need to prepare for the next stage. Something Orwellian, or more Huxley? Arguments can be made for and against, but now, as technology gives governments the means to an uncertain end, we follow a path that seems decided for us, despite the lessons of history. Censorship, in the broadest sense. Everything watched, considered and, inevitably, acted upon. And following this, and worse, the self-censorship that logically follows. So, now we need to decide. Where to draw the line. A toe bone here, a mandible there. Do we shrug, make the best of it? Or stand up, and speak out? Dissent. In the genes, perhaps? Take, for instance, Sydney Sparkes Orr, born in Belfast (of course) who migrated to Australia and secured a position at the University of Tasmania. He didn’t like the way the place was run and wrote an open letter of complaint to the premier which was published in the Mercury on 29 October 1954. This led to a royal commission which found the university council should be replaced. The Tasmanian parliament then passed a new university act. Days later, the ball was returned: a university committee was formed to hear complaints about Orr from other academics, and another, from a local timber merchant who claimed Orr had seduced his undergraduate daughter. Orr was sacked, and this led to years of debate, wrongful dismissal claims and eventually, a boycott of Orr’s chair of philosophy from sympathetic academics. Sydney was no angel, but his problems began with the need to speak out. I’ve seen this a lot. My Year 10 art teacher (let’s call him Rob) became a minor martyr for we of the pre-fab art room. He spoke his mind about school structures, and personalities, and mysteriously retired soon after. We didn’t know the facts about Rob, so we invented. Painted a halo around his head and remembered him as a John Lennon in acrylic. Speaking of whom, we had the Lennon T-shirts, and quoted the songs (“You can live a lie until you die, one thing you can’t hid is when you’re crippled inside”). He was already dead, but that didn’t matter. Then I discovered the king of dissent: George Orwell. To me, he did, and does, get everything. My favourite quote: “The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness and for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better.” Today, we see this everywhere. The need to avoid the uncomfortable (Orwell always said he had the “power of facing unpleasant facts”) and instead, skol our whey supplements as the world self-destructs, as it’s always done, I guess, except now we have Netflix to make things better. Newspapers elevate trivia to news. Three-legged dogs are more noteworthy than barrel-bombed children. Anything that requires a reading age above 11 is no-go; complex arguments are sacrificed to sound bites. Each day we become smarter, yet less willing to use our intelligence. Happiness is better. Not that I think we should walk around depressed, endlessly analysing every point-of-view, media release, overheard comment. That seems to be leading us towards a don’t-let-that-bastard-merge sort of society. But to just accept what has been decided on our behalf? By newspaper editors who don’t read, understand history, context, culture; politicians looking for the next circus to distract us from the failure of their backward-looking policies (every thought fiscal as they hasten towards their superannuated heaven). Patrick White was another grumbler (apparently). I wonder what he’d make of Australia today? As we still sail, run, sprint, walk, sweat our way from one flag to another. As he explained, “This passion for perpetual motion – is it perhaps for fear that we may have to sit down and face reality if we don’t keep going?” All of which leads to one of Orwell’s favourite topics: censorship. Today we have a situation where the federal government requires Australian telecommunication companies to keep customer records for two years. Mandatory data retention allows your government to keep your information without your permission, or the need for a warrant. Metadata describes your life in the digital age: phone calls (including time and duration), IP addresses, times of internet sessions. It’s sort of comforting. Online abusers, terrorists, others who’d seek an easy path to unsavoury acts, having their lives made difficult. But where was the debate about what we’d need to give up? When the idea was first mooted, a few voices were raised. The government explained it couldn’t access the content of emails or phone calls. In a way, it didn’t matter. Cross-referencing is a valuable tool. There was a concern that journalists would be stripped bare, their bleached bones visible to all. Did it matter? Three-legged dogs and a few torn hamstrings? But what about the journalist (and it only takes one, Orwell explained, “printing what someone else does not want printed”) who’s just found out what a miner is pumping into a river? Thing being, you gotta protect your sources. This led to a compromise between government and opposition: a public interest advocate to argue against police access to journalists’ information. But it seems a weak concession, hastily conceived to gain Labor support to pass the legislation. Orwell explained that, “If you want to keep a secret you must also hide it from yourself”. Winston Smith tried, but failed. Maybe, in the future, the whole freedom versus happiness conundrum will lead us to point where every thought, notion, instinct is self-censored as it emerges. Before being euthanased, and eventually forgotten. Maybe, in time, this will lead to the end of dissent? As Whitman’s procreant urge of the world withers and dies on the vine. Bones crumbling, patella, shin, into the sea. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei became a reluctant warrior in the battle for the sanctity of self-expression and, ultimately, -determination. Hounded for years for his challenging images, arrested, tried, released ‘on bail’, in an essay on self-censorship he concluded, “Intimidation is the most efficient tool for those in power to scare away people’s sense of independence…Censorship [removes] people’s courage to make judgements or bear social responsibility”. The power of art, words, opera, has always frightened the poseidons of the cruel (fascist) sea. Historically, artists have steered the most delicate path. Thomas Mann called Richard Strauss a “Hitlerian composer” because he continued working under the little corporal, accepted the presidency of the Reichsmusikkammer (RKM) and, early on, supported National Socialism. Nonetheless, Strauss had no problem with Jewish composers such as Hofmannstahl and Mendelssohn, and even worked with a Jewish librettist (Stefan Zweig). “I just sit here in Garmisch and compose; everything else is irrelevant to me.” Hitler sent him an autographed portrait, and Strauss wrote an Olympic hymn. But when the composer sent Zweig a letter saying his role with the RKM was “play acting” the Gestapo intercepted it (a sort of early metadata moment) and showed it to Hitler. Fair to say, Strauss was having a few bob each way. Dmitri Shostakovich seemed happy to toe the state line. “Real music is always revolutionary, for it cements the ranks of the people; it arouses them and leads them onwards.” Although after his death many (most notably Solomon Volkov in 1979’s Testimony) suggested otherwise. Self-censorship filters down. The art of exclusion. Authors of text books deciding what to leave out. Publishers. Do we really want any more dreary novels about angst? What about this one, about a man who finds love on the Harbour? In the end, like Strauss, we start to question what we do believe. I’m not of the opinion that our leaders have any grand 1984 vision. That would entail an understanding of history they don’t possess. More, perhaps these things just happen where, as Edmund Burke explained, good men fail to act. Orwell, again: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” Which is sort of the opposite of watching Mad Men and endless house renovation and amateur cooking shows while drinking our own soma. Which, apparently, offered immortality. But, of course, doesn’t. Quite the opposite. Only ideas offer immortality. If they have the freedom to be expressed, explored, communicated, like Sydney, facing his star chamber, reduced to odd jobs and despair. Orwell, only worried about the well-being of others. Staying distant from his son, so he wouldn’t catch his TB. As he wrote his masterpiece, warning us of the disease which continues spreading, cell by cell, search by search. Lennon, still in bed with Yoko, arguing for peace in a world that is still characterised by conflict. And what about Rob? He let us paint murals on the side of the art building, but later, when he’d gone, the groundsman painted over them in beige. Beige. Like a life without dissent. Too happy to be worth living.

Stephen Orr’s latest novel The Hands has just been released through Wakefield Press