Royce Kurmelovs

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).

At the front of the room sat the Senator and the Economist. In front of the Senator was a glass of water

By the left hand of the Economist stood a pint of beer. Both were perched atop bar stool at a high table. A microphone amplified their voices for the audience of around 65.

The Economist was a numbers guy who cracked jokes about tax policy. The Senator looked tall and thin and nervous as he read out his CV from his first 500 days in office before the microphone went around the audience and questions started coming in from the floor. The Senator’s answers were sincere, if clumsy at times, and when he spoke, he had a way of talking with his hands while trying to articulate a specific point.

The first question was from a woman representing the unemployed who wanted to know why the Senator had supported extending the Cashless Welfare Card trial? The next question was from a member of a union. She asked about his attitude to privatisation. The one after that was about water issues, then a question about the influence of minor parties and then another about water management. Each time the Economist was a little quicker to answer at length.

During one of The Economist’s answers, Pam Coutts stood up. She was wearing a red beret and a red vest and was no taller than five foot eight. The question asked, she told the Economist, had been directed to the Senator. Those in the audience had come to hear what the elected representative had to say about the issues and so, she asked, could he please leave the Senator to answer in full?

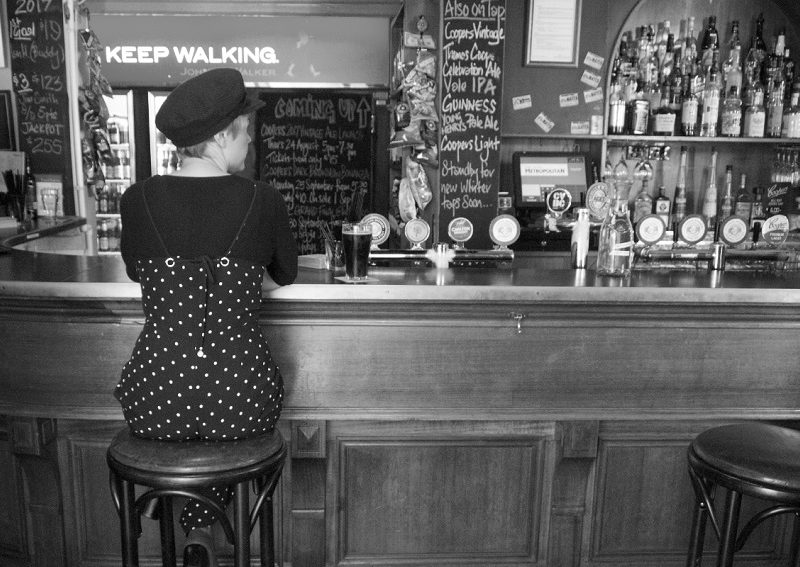

“A lot of people sitting near me were whispering about it, so I felt like I had to say something,” Pam says over an hour later, while sitting at the bar with a glass of shiraz. She was a teacher once, she says, and so has no problem speaking to crowds. She talks plainly and explains her personal political philosophy with a quiet certainty.

“I firmly believe in getting politics into the community,” Pam says. “I want to see it become respectable. I want people to see relevance in it. And the way they’ll get relevance is if they eyeball a politician and hear their answers to their questions.”

Politics today has become so closed, Pam says. Wannabe politicians go out and get a law degree and then get a job in a political office. There they learn the trade but know nothing about life. Pam started out raising hell over in Melbourne with the teacher’s union and was an active member of the Labor Party in her younger years. In time she knew all the major players. Bob Hawke once lived down the road. And of her two marriages, it was the second which stuck and from the moment she met her husband, there would be no one else.

“People say they’ve been in love,” Pam says. “But I don’t think many really have. It’s something chemical. It’s like no one else exists.” Her husband was an electrical engineer who helped develop the nation’s first mobile phone. It was through him she would become the second person in the country to hold one outside of a Telstra research lab when he brought it on holiday to field test it.

Around that time, their world changed. Labor started moving to the middle, so she resigned from the party in protest. Pam lost her job in the community sector when a change in government cut the funding. Her husband had a job offer at his old university back in Adelaide, and so, though he had sworn never to go back “other than in a box”, they packed up their kids and the three cats to make the trip west along the highway.

They found themselves a beautiful sandstone house and settled in, but for the next 16 months Pam would struggle to find work. It was a period she describes now as “soul destroying”. With time she picked up a job as a researcher. At age 50, she tried her hand at a phD.

It would never be written. Her son, Paul Coutts, had cerebral palsy from a bungled operation when he was a baby that meant he had to use a wheelchair for life. He was bright and intelligent, and when he came of age, he wanted to live independently. So after high school he moved into a group home for the disabled, but when he endured neglect by staff, Pam quit her research to fight for his rights. “You should never have to beg,” she says firmly.

Eventually they won and, at 22-years-old, her son had his own home. For the next eight years he lived a full, active life. He started a business. He was a foodie. Then at 30-years-old, he passed away from sudden, unexpected heart failure. Pam was with him when it happened. Two years on, Pam still speaks about Paul in the present tense. The grief is chronic, she says, but it’s lifting. She’s getting back out into the world now and is starting to follow politics again. She even rejoined the Labor Party. That’s why she’s here tonight, she says. Right or left, it doesn’t matter. What she wants out of politics is a little conviction.

“You’ve got to have passion,” Pam says. “But that doesn’t seem to be acceptable nowadays. Only in the films.”

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).