Andrew P Street

Andrew P Street is a freelance writer whose books include The Short And Excruciatingly Embarrassing Reign Of Captain Abbott (2015) and The Long And Winding Way To The Top (2017).

The long-overdue release of the Palace Letters makes one thing clear: Australia needs to become a republic if it wants to save itself from political traitors seeking to undermine our democracy.

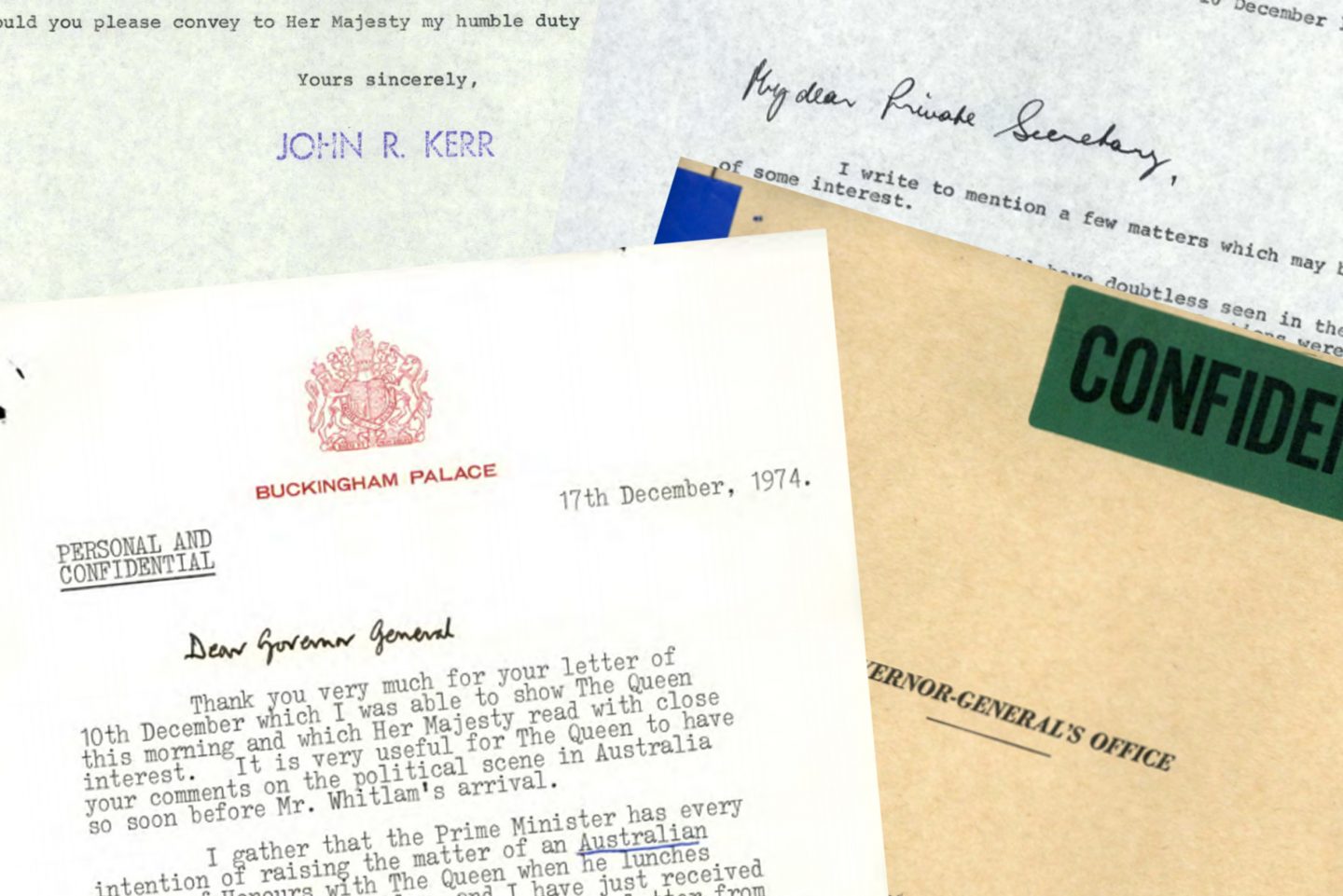

Let’s jump straight to the end: thanks to the release of the Palace Letters we now know that our monarch consented to remove Gough Whitlam, the elected Prime Minister of Australia, with the support of the Liberal Party because Governor General John Kerr was scared that he was going to lose his job and Malcolm Fraser was absolutely prepared to use Kerr’s paranoia to his advantage.

For those unaware of the events of November 1975: the Whitlam Labor government were struggling under the weight of multiple scandals, as well as dealing with an increasingly hostile Senate where the balance of power was held by the conservative Democratic Labor Party.

In October Fraser, the then-Opposition Leader, used Liberal and DLP numbers in the Senate to block supply bills – the things which authorise the money that keeps government operating – in the hope of forcing Whitlam to call a lower house election. Instead, Whitlam sought to call a half-senate election in the hopes of getting more favourable upper house numbers and on November 11 1975 he met to advise Kerr about this plan, as the law dictates, except that Kerr instead dismissed Whitlam as PM and installed Fraser as caretaker PM ahead of a double dissolution election in December, which the Liberals won in a landslide.

For almost half a century Australians have not known the answer to basic questions like whether our monarch was aware of the actions of her Australian representative, or even the timeline which led to Kerr making his unprecedented move. And then on Tuesday 14 July 2020, that all changed.

Academic Professor Jenny Hocking has spent decades launching legal challenges to release the discussions between Kerr and the Palace, which has been blocked on the frankly insulting grounds that it’s private correspondence between the Governor General and the Queen – heck, it could have been 211 perfectly innocent enquiries about the Monarch’s health and what magazines she’s been reading! – until the High Court ruled earlier this year that the letters must be released.

You can see why the Palace were so damn keen to keep the papers under wraps, since Elizabeth is the only principal character still with us. Of those who have passed on, Whitlam is the only figure who emerges with his dignity intact. The Palace Papers show Kerr as a paranoid little man obsessed with the idea that he and Whitlam would be caught in a “race to the palace”, to Malcolm Fraser as a shameless opportunist, and the Queen as unambiguously overstepping her role as the non-partisan figurehead of our Commonwealth with the help of a private secretary evidently more than happy to help instigate a colonial coup.

And the Palace have long known how badly this paints our reigning monarch. Her current private secretary Mark Fraser argued that the letters should not be released in the interests of preserving “the constitutional position of the Monarch and the Monarchy,” and he was right. It’s definitely not helping preserve it.

See, the story goes that “as Head of State The Queen has to remain strictly neutral with respect to political matters”, and yet these letters demonstrate that the Palace was getting very, very interested in what was happening in our federal parliament.

There’s no doubt that monarchists will argue that since the correspondence was between Kerr and the Queens’ private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, there’s no proof that Liz herself even knew that there was a problem with the government, or even what an Australia was. Of course, this line of defense rests on the Queen being damningly incurious and ignorant, if technically innocent. It’s a bit like James Murdoch telling the Leveson Enquiry he was unaware of News of the World’s illegal phone hacking because he hadn’t scrolled down to read the full email chain telling him about it: not exactly ideal.

But the main thing which comes out is how paranoid Kerr was that Whitlam was going to sack him. In one of the letters Charteris seems to reassure Kerr that the Palace totes has his back: “Prince Charles told me a good deal of his conversation with you and in particular that you had spoken of the possibility of the Prime Minister advising The Queen to terminate your Commission with the object, presumably, of replacing you with someone more amenable to his wishes. If such an approach was made you may be sure that The Queen would take most unkindly to it.”

And the letters confirm that it was the Palace which suggested that Kerr could invoke the Reserve Powers of the Governor General if he wanted to, say, remove Whitlam. “When the reserve powers, or the prerogative , of the Crown to dissolve Parliament (or to refuse to give a dissolution) have not been used for many years, it is often argued that such powers no longer exist,” writes Iago – sorry, I mean Charteris. “I do not believe this to be true. I think those powers do exist… But to use them is a heavy responsibility and it is only at the very end when there is demonstrably no other course that they should be used.”

That’s the constitutional equivalent of telling Kerr that look, there’s a pistol with the serial numbers filed off in that drawer over there and what he chooses to do with that information is totally up to him.

One thing the Palace Letters don’t contain: Charteris dismissing Kerr’s whiny night-terrors and telling him that Australia needs to sort their domestic political issues out themself, not least because a supply bill dispute is a party political issue. The palace could have – and actually should have – insisted that this was outside of their remit and declined to respond further, not offer sympathy and strategy.

So, the papers are a fascinating and infuriating read. And as Mark Fraser accurately feared, their release absolutely undermines the current monarchy. But I’ll go further:

The biggest thing which the letters demonstrate is that the same loopholes which allowed an unelected factotum like Kerr to undermine the Australian government still exist today, and that we cannot assume that our monarch will behave nobly. The Palace Papers prove that the case for an Australian Republic isn’t merely philosophical: it’s urgently necessary to safeguard the continued functioning of Australian democracy.

Andrew P Street is a freelance writer whose books include The Short And Excruciatingly Embarrassing Reign Of Captain Abbott (2015) and The Long And Winding Way To The Top (2017).