Michael O'Neil and Peter Gill

Michael O’Neil is Executive Director at the SA Centre for Economic Studies, University of Adelaide. Peter Gill is a Research Associate at the SA Centre for Economic Studies, University of Adelaide.

Some Coalition members may resist extending JobSeeker’s COVID-19 increase, citing concerns higher payments would remove incentives to find work. Setting aside half the increase for training could remove the roadblock.

The government is about to make an historic decision.

The JobSeeker unemployment benefit (previously called Newstart) has scarcely increased in real terms since 1994.

In that time general living standards, as measured by real gross domestic product per capita, have almost doubled, climbing 83%.

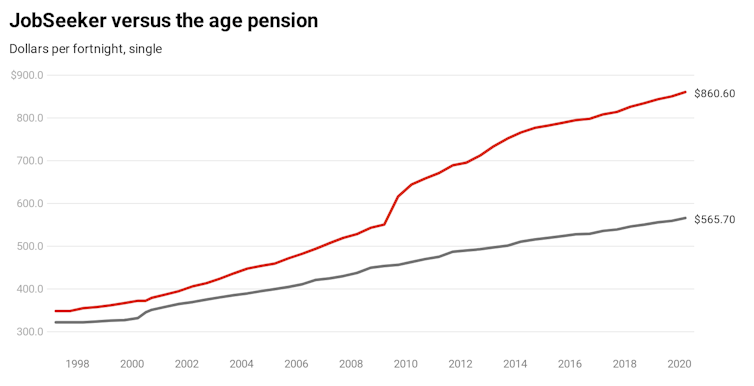

Other benefits such as the age pension have broadly kept pace with living standards. They climb in line with wages rather than the slower-growing consumer price index.

In dollar terms the single rate is now just A$565.70 per fortnight, close to the poverty line and well below the $860.60 paid to single pensioners. Back in the early 1990s it was close to the pension.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development said in 2010 Newstart had fallen so low as to call into question its effectiveness in “enabling someone to look for a suitable job”.

In March, as the scale of the looming job losses from coronavirus and the responses to it became clear, the government effectively doubled JobSeeker, boosting the $565.70 single payment and other lower payments by a $550 per fortnight coronavirus supplement in an acknowledgement that unemployed people “need to meet the costs of their groceries and other bills”.

The increase took effect from April 27, but was temporary, for six months after it received royal assent, meaning it is due to expire in late September.

The economic statement due on Thursday will provide an opportunity for the government to cushion the blow by either extending the life of supplement or permanently lifting JobSeeker.

It’ll also provide an opportunity for it to say no, allowing JobSeeker to collapse back to where it was.

An increase suggested to the recent Senate inquiry by the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies was $80 to $120 per week, enough to restore it to where it was relation to other benefits in the early 1990s.

But the government will need to get over its seemingly ideological premise that the unemployed are in some way responsible for their own misfortune and are usually undeserving of the support needed to meet living costs.

This sentiment on display in the dissenting report by Coalition members of the Labor and Greens dominated inquiry which recommended JobSeeker be increased.

In explaining their position in April, after the the government had temporally doubled JobSeeker, Coalition Senators Wendy Askew and Hollie Hughes, argued that a permanent increase could carry with it “disincentive effects in respect of engagement with the workforce”.

Put plainly, they were concerned that if JobSeeker was boosted to a reasonable level (as it has been, temporarily) people mightn’t want to work.

Yet the transcript of evidence given by treasury officials at the inquiry reveals the department has never been asked to examine that question.

Asked whether the treasury had ever done any modelling of an increase in the payment now known as JobSeeker, deputy secretary Jenny Wilkinson relied “no”. Asked again: “You’ve never done that?” she replied “no”.

Others have done the analysis.

Deloitte Access Economics believes an increase would boost the size of the economy and boost the number of people employed by 12,000.

A compromise that might be acceptable to members of the Coalition who oppose lifting JobSeeker but support “job-ready” training programs, might be an increase in the JobSeeker allowance of, say, $80 per week, split into two.

Half of the increase would be a cash increase without conditions, the other half would be provided for accredited training.

With conditions in place to ensure participation in bona fide training, the increase could drive the skills development both employers and the unemployed want.

The training that would emerge would be market-driven, responding to the post-COVID-19 needs of employers and potential employees.

The Productivity Commission has implicitly endorsed such an approach, reporting in May that there was “a manifest capacity to better allocate the $6.1 billion in government spending on vocational education and training to improve outcomes”.

JobSeeker could help, both supporting Australians who are out of work and supporting them to get back into work.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Michael O’Neil is Executive Director at the SA Centre for Economic Studies, University of Adelaide. Peter Gill is a Research Associate at the SA Centre for Economic Studies, University of Adelaide.