‘I am an Anarchist – So What?’

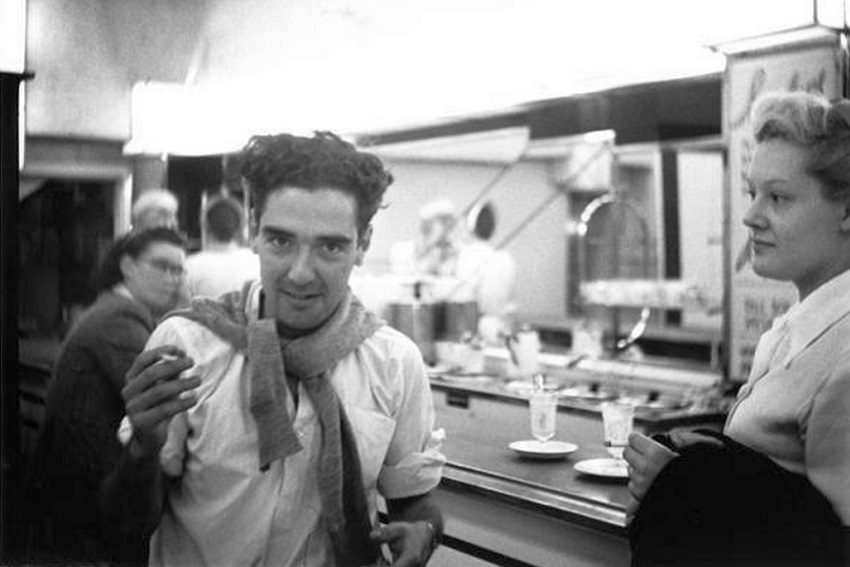

Reflecting on Max Harris and the infamous Ern Malley affair, Stephen Orr highlights how one of this country’s great poets was determined to drag Australia into the 20th century, the century of free speech.

1944. A young student, poet and editor by the name of Max Harris is sitting in an office in Grenfell Street, working on a new edition of Angry Penguins, a modernist journal of ideas he’s founded (his mum has bankrolled the first three editions) with Sam Kerr, Paul Pfeiffer and Geoffrey Dutton. Harris has a deadline, as well as approaching exams, and his head is full of words. Perhaps the story of mad Jasper “poised on the skyscraper wall”, the poor boy feeling “this the moment to end all”. Two men come into his office, and one, Detective Vogelsang, says, “We are police officers. What is your name?” Max tells them, and Vogelsang asks if he is the editor of Penguins. Max says yes, although John and Sunday Reed, and Sidney Nolan, are part of the editorial committee. Then Vogelsang asks about this poet, Ern Malley, and says, “We are making enquiries in connection with the provisions of the Police Act with respect to immoral or indecent publications.”

As history shows, nothing was quite the same for Max Harris after that autumn afternoon. Max, the Renaissance man, bringing Rilke to Rundle Street; Max, bookseller and stirrer, this Athenian Everyman, increasingly lost in the white noise of our junk culture. He was the Colonel Light of the Mount, the Sarte of Sigalis’s, testing and rejecting what it meant to be South Australian. Born April 13, 1921, spending his first 13 years in Mount Gambier, where “the children were pretty tough and I lived in a fair degree of physical fear”. Accompanying his father, a travelling salesman, on his trips around the state, all the time soaking up a feel for the place, the picnic races, the “kegs in the flapping canvas booths”, a childhood haunted by the Tantanoola Tiger’s “burning eyes”. This mithridatum of despair for a father who never really acknowledged his son’s gifts. All of this finding expression in the Sunday Mail’s Possum Pages, and later, in a series of publications beginning with the The Gift of Blood, a group of poems dripping Eliot and Pound (and others), although so what, this was Adelaide, the era of cardigans and unscented talc, and here were poetic rustlings in the cultural undergrowth.

There followed a scholarship to St Peter’s College, a 15 shilling a week job as a copyboy at The News, a short-lived stint in the army, before Max really got started praising the “cobbles of the square”, describing the difficulties of tying one’s shoelaces by the fogged lamplight. A man, strangely, at one with his wheat-sheep town, but at the same time aware of the “dull eternal sea” that characterised Playford’s city-state.

Angry Penguins would take care of that, he thought. Shocking. Modern. None of the Jindyworobaks and their gums (although they published his Gift). Penguins would be a taste of Europe. In a 1939 article Harris admitted he was a member of the Communist Party. Black shirts and white ties, parading around university with the ever-faithful Mary Martin. Colin Thiele remembered him talking about Keats’s letters in an Honours tutorial: “He got into Kafka and Rilke and German symbolism, swept through French poetry … had a go at Whitman and Robert Frost, touched on Yeats and James Joyce…” Although by the end, he hadn’t actually mentioned Keats’s letters.

At this point, an observation. I think Max Harris was one of our best poets. But all of his word-clanging and special effects (that he eventually grew out of, saying in 1979, “If I had the courage, the poetry I publish now would be nameless”) was overshadowed by Ern and Eth… you know, Malley. Anyway. Take Disintegration of an Echo. “The melancholy blackbrown negress…” or mad Jasper, deciding whether to leap from “life’s concrete parapet.” I first read Harris at school, where some of his poems were included in Rigby’s 1976 Mainly Modern anthology. We were made to sit and read this man described as a “journalist and TV personality”. Although that missed the point. Surely a poet is a poet first? How we should remember Max, in my opinion. As the sun beat down on the glass windows we read about Max at the circus, “engulfed in an ache of want and pity/For the lady’s body, oiled as hawk…” The caravan desires (this got me thinking). This boy, unable to “sex effect and cause”, waiting for something to go wrong (“And their broken limbs lie dreaming beneath the trapeze”).

In 1943, Ethel Malley, from 40 Dalmar Street Croydon, Sydney, wrote to Max. “Dear Sir, When I was going through my brother’s things after his death, I found some poetry he had written.” You know the story. Naughty James McAuley and Harold Stewart, trying to bring the pretentious Max down a few pegs, inventing Returned soldier Ern Malley, and his secret beneath-the-sheets scribblings, hidden from the world, later discovered by his sister, Ethel, sent to Max, who was knocked out by the poems. He wrote back to Ethel: “I should have no hesitation in publishing the poems…” Which appeared in a special Ern Malley edition of Penguins. Followed by the real poets’ admission of guilt, or pleasure, or whatever it was, all to the embarrassment of the journal’s co-editors. At first Max took it well, but by the time Vogelsang visited, things were changing. Max once said “…the whole bloody mob will lynch me one day, for not spelling culture with a capital K/And now I’ve been gunned by this bloke McAuley.”

Yes, there were a few blue bits. In Boult to Marina, for instance, “Part of me remains, wench, Boult upright/The rest of me drops off into the night…)” But mostly, the poems were No Frills modernism. The great irony is that they’ve lasted, become the works of art their authors (apparently) never intended. From the opening lines of the suite’s fist poem: “I had often, cowled in the slumberous heavy air/Closed my inanimate lids to find it real…” We hear poets at work. Maybe if they’d got their nine-year-old cousins to write them instead?

So, Ern appears, consumed by a small readership. Until the police receive complaints. Ern, this rotten pornographer, upsetting Adelaide sensibilities. Vogelsang visits Max, and the next thing, an obscenity trial is set down for September 5, 1944. John and Sunday Reed fly over from Melbourne, Max declares he’s finished with Australia and “the country [is] not a fit place to publish serious work”. John Reed tells him, “For goodness sake, don’t let us have that.” Harris later says, “Overall the last few months [made] a pretty deep and permanent impression on me.”

Max pleads not guilty to the charge of publishing obscene material. Vogelsang (known as ‘Dutchie’) asks him about the poem Sweet William (“To where in a shuddering embrace/My toppling opposites commit/The obscene, the unforgivable rape”). Max explains, “I don’t know what the author intended by that poem. You had better ask him what he meant.”

As one imagines the steam actually rising from beneath Vogelsang’s pressed shirt collar. These two Adelaides going head to head: the respectable Methodist version, and the Max Harris version, determined to drag people kicking and screaming into the Twentieth Century, the century of Ulysses and Lolita, the century of free speech.

Vogelsang tasted blood. “You admit then that there is a suggestion of indecency about the poem?”

“No, I don’t. If you are looking for that sort of thing, I can refer you to plenty of books and cheaper publications…”

This Dalton Trumbo figure, standing up to a local bully. The same year, William Dobell in court defending his Archibald-winning painting of Joshua Smith. Portrait or caricature? What did it matter? What mattered was the creative impulse, the result, and people’s enjoyment (or lack thereof). What Max meant, McAuley, Stewart. What Robert Close meant, in his novel Love Me Sailor. Lawson Glassop’s We Were The Rats. And if I mention Charlie Hebdo, I can hear so many saying, “Ah, yes, but that was different”. But was it? Wasn’t that exactly what Max was standing up for; the contraceptive to his own writing and publishing after the trial? Was Max a victim of censorship, of Vogelsang, of Adelaide itself?

Max Harris grew up in a different Australia. He always spoke out about bigotry, the biggest bully having the last word. Some national traits keep emerging from the undergrowth. South Australia boasting a government that, on one hand, defends Bill Henson’s right to freedom of speech, but on the other, shuts down any opposition to its policies via a carefully monitored and maintained public service, supplemented with lashings of feel-good propaganda aimed at convincing us the next big thing (read stadium, concert, race) will keep us Palmolive clean and happy. In one of his 1960s columns in The Australian, Max quoted Queensland Country Party MP, Russ Hinze: “The appeal of the play Hair, could only be to those who could be regarded as sexually-depraved, or a group of homosexuals, lesbians, wife-swappers or spivs.”

All this decades after the Harris/Vogelsang standoff.

I think Max should be on the 50 dollar note, or at least our state flag, hanging out with Mary, or John and Sunday, in his little bookshop, with its table full of remaindered ideas.

Stephen Orr’s latest book Datsunland (Wakefield Press) is out now

Header image: Wikimedia commons