Royce Kurmelovs

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).

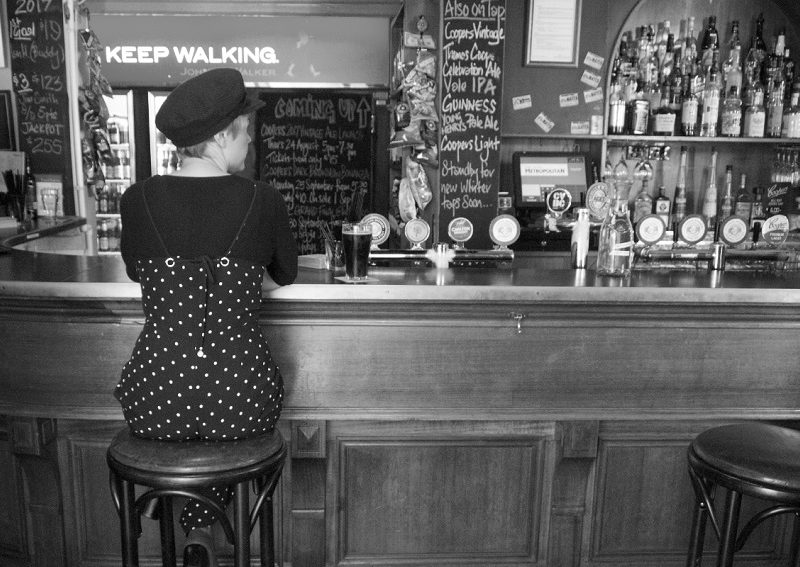

After quitting the corporate world to become a children’s entertainer, Andrew Ormandy discovered the joy, powers and occasional heartbreak that come with being Santa, as he tells Royce Kurmelovs at the Sussex Hotel.

“The CEO asked me what I was going to do when I’m gone,” says Andrew Ormandy while sitting out back of the Sussex Hotel on Walkerville Terrace during a Thursday afternoon. “And I told her I’d be a clown.”

Every Thursday, Ormandy, 55, meets a couple of the guys for a drink. Each buys a round, for four rounds in total, but drinks were cancelled tonight as the other guys are away. Instead, he offers to buy me a beer in return for telling me how he quit the corporate world.

It started the day he walked into a magic shop on Melbourne Street run by a man called Magic Mike. Mike had the sparkly vest and the smile of a showman and just setting foot in the door reminded Ormandy of being 13 years old when his Nan used to take him across the Sydney Harbour Bridge to buy a trick from the magic shop. Every Wednesday night, Mike would run magic classes for those who wanted to learn the art of illusion and misdirection and the bait and switch – Ormandy signed up.

“Mike taught me everything I know,” Ormandy says.

These days they’re in business together and Ormandy is running his own set of characters such as Bumbles the Clown and Amazo the Magician and Santa’s bumbling helper elf Alabaster Snowball. Probably his most successful character is Third Degree Burnie, a flame magician who thinks he’s good, but really isn’t. Next year Ormandy’s taking Third Degree Burnie on tour to Las Vegas to play what will be the biggest shows of his three-year-career.

This time of year, though, the only show in town is the jolly fat man in the red suit. Unlike the supermarkets who may have three Santas working for a wage across three separate shifts, Ormandy is a freelance Father Christmas.

Volunteering to wear the uniform also comes with a certain level of responsibility.

Andrew Ormandy, the man, is the guy who sat next to Tony Abbott and Brendon

Nelson in high school. He was the shark salesman who used to answer emails at 3am. He was the guy who thought he had the best job in the world at the charity where he worked until his psychologist told him that the feeling he was getting had a name: depression.

As soon as the whiskers and the pointy red hat go on, there is no more Andrew Ormandy, there is just Santa. The first rule of being Santa in a place like Adelaide is that you don’t work before Pageant. The big guy in the sleigh arrives with the parade, never before.

“And you know, there’s an art to being Santa,” Ormandy says. “It’s not a matter of ‘whaddya want?’”

Santa doesn’t drink and doesn’t swear. Santa treats everyone equally, be they adult or child, rich or poor. Getting crowd control at a private show is as easy as asking whether the children have been naughty or nice. When they ask for something ridiculous like a Porsche, Santa tells them his auto shop made the last one yesterday. When they ask for something their parents can’t afford, Santa repeats the request out loud to mum or dad and waits for them to shake their head so Santa can let them down easy.

It’s the clever kids who are tricky. A little girl will say she’s seen Santa at one supermarket and then again at a second and she’ll want to know how he can be in two places at once. Santa tells them that’s the magic of Christmas. It’s a kind of logic that makes sense to a child.

The hardest times in the job have a way of sneaking up on you, he says. Once an elderly couple came up to Ormandy after a show and told him about their grandson. It was cancer, they said and the doctors thought he might not make it to Christmas. Ormandy’s brother-in-law Ernie was dying of cancer at that time too. Ernie was 68. The kid was six. Andrew said he’d do it for free and told them to call as soon as it looked like bad news.

He never heard from them, though. He figures it was because the doctors had it wrong.

“We’re an angry society,” Ormandy reckons. Everyone has a phone and everyone with a phone has instant access to the worst of humanity. Santa is like an antidote to that, he says, just like magic. It’s something to help shake the feeling that everything and everyone is mean, proof positive that it is still possible to feel wonder or awe.

It’s why he’s hoping to put on the suit once more this Christmas Day. Last year, he played Father Christmas at the Maitland Hotel but so far he doesn’t know what will happen this year. Not that it matters. Ormandy has his wife of 37 years and two fully grown children who are chasing lives of their own.

Even if he doesn’t get the call, he knows where they’ll be, and that’s enough.

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).