Royce Kurmelovs

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).

From Vietnam to Virginia, Tor’s a farmer with an incredible story, as he tells Royce Kurmelovs over a mid-harvest beer.

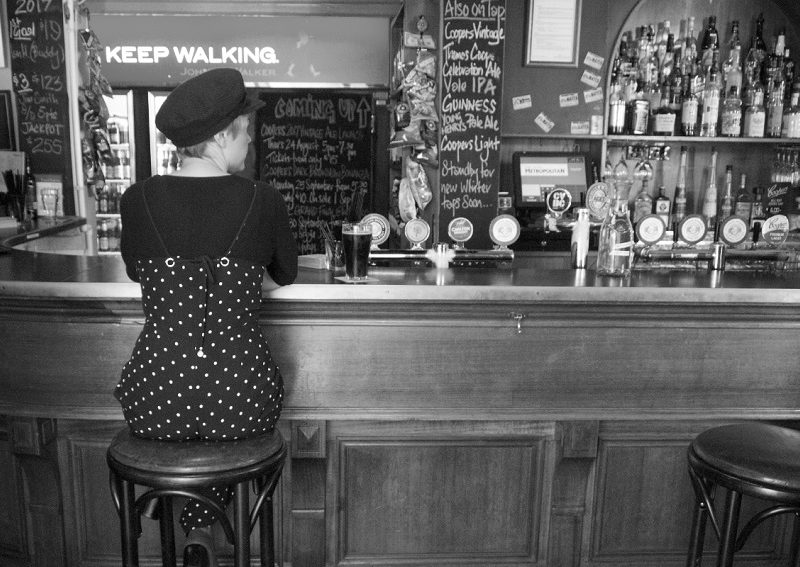

Today is the first time Tor has seen Sang in about five years. It’s the middle of harvest, but Tor isn’t so busy he won’t set aside an hour to drink with an old friend, so he pulls up a couple of stools around his kitchen bench and takes a side of ham from the fridge. He slices it into squares and puts it on the table next to his home-made olives. He cracks three Coronas from the six-pack next to him and passes over two.

“You need lemon?” he asks.

We don’t, so the glasses clink while the two get to catching up. Half the conversation is in Vietnamese and the other half in English. Both men are members of the first generation who risked everything to make a life somewhere else and the conversations always seem to follow the same cycle. They talk about the business and the harvest, about politics and their kids. The next generation, they worry, doesn’t understand what they went through.

In this way, every conversation comes back to the old country and the war. Sang’s 62 now, but he knew the sound of gunfire and the smell of a corpse before he had come of age. His father was a professional, which made him a member of the intelligentsia, while his uncle had been a captain in the South Vietnamese Air Force. That put his whole family on the losing side of a bitter fight and the best they could have hoped for in the aftermath was to spend some time in a re-education camp before being left to a life of poverty. Chances were, they’d never even make it that far.

In 1976, when he was 18, Sang’s whole family slipped away one night headed for a refugee camp in Malaysia but when they hit land, the local cops told them the camp was full. So the six boats in their little flotilla kept on, heading south until 145 souls washed up on a beach in Darwin before settling in Adelaide.

Tor left a little later. At 56, he’s a little younger than Sang and started out as a farm boy about 60 kilometres outside the capital where the new regime did him no favours. In 1981, the local government official got drunk one New Year’s Eve and stumbled out of his house, firing into the crowd. The first shot went right through Tor’s chest. The second went into the air.

Tor pulls up his worn flannel shirt to show the scars. He spent a month and a half in the hospital, and while the government compensated him for his trouble, they still ended up taking his family’s land. With nowhere to go, they left for a camp in Thailand before finding their way to Australia.

“We came for a better life,” Sang says. “Everyone did. Adelaide had a warm heart.”

Four decades later since that first boat arrived, a lot has changed. One of their own, Hieu Van Le, is living in Government House, Sang’s four kids all have jobs and Tor’s got his own land out near Virginia. Sang helped him get the money to finance the whole operation and, about six years ago, Tor built his house on the plot so he could escape the suburbs.

Every morning, Tor wakes to tend the soil and work the 76 plastic wrap grow-houses spread across eleven acres. It’s not an easy life, he says, and every year is a gamble.

If Queensland floods, the price in South Australia goes up and Tor lives well. If Queensland does well, the price down south drops and he hurts. If the grow-house gets too cold, the fruit gets mouldy. If it gets too hot, the fruit goes too soft and no one will buy it. When the temperature looks like it will be 40 degrees the next day, Tor will be out there at 2am picking fruit.

Each grow-house, he says, costs $5000 to build and if the wind picks up debris, it shreds the plastic covers and costs another $1000 to fix. Get sick and you’re not out picking, which means you’re losing money. If the plants get sick, you’re putting money in for chemicals. Lose too much of the crop and it’s easy to go bust.

“Some people go too big too fast,” Tor says, waving a hand. “I want to be stable.”

And when the harvest is over, there’s nothing to do but wait. That’s when all the old men gather from all around to drink beer and rice wine and talk about the season, about business, about their kids and the old country. They talk about the war and how they fled the communists and they worry their children don’t understand what they went through. Sometimes, the party can go for three days, Sang says.

“You couldn’t handle that, young man,” Sang tells me.

I tell him he’s probably right.

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).