Walter Marsh

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

As institutions around the world work to return Aboriginal ancestral remains to Country, more than 4600 Old People wait in storage at the South Australian Museum. A new Museum policy has committed to their repatriation, but to complete this massive task will require non-Indigenous South Australia to join the journey – and reckon with its own complicity.

“No one wanted to be accountable; once these burial grounds got dug up or our Old People were found, they’d quickly bring them to the Museum,” Kaurna Elder Jeffrey Newchurch tells The Adelaide Review. “The question didn’t really come in until the Aboriginal Heritage Act in 1988 gave Aboriginal people a position – even if that was only through conversation or small-time engagement.”

“There was a policy, but it wasn’t really a policy,” the Museum’s Head of Humanities, Professor John Carty, says of the Museum’s earlier stance on repatriation. “It was a document from 1987 saying, ‘We’d like to do the right thing, but it’s hard.’ It didn’t really commit to reburying people, didn’t commit resources or people to it, and was written before the Aboriginal Heritage Act.”

Although written prior to the issue of repatriation being enshrined on a national and international level through the 1988 Aboriginal Heritage Act and the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People, the initial progress that this decades-old “piece of paper” signified had stalled in the intervening years. And as recent years saw institutions from Sweden, Austria, England and Scotland return Old People, the apparent inertia of Australia’s biggest holder of Aboriginal ancestral remains was glaring.

“Historically, it’s the same in every museum,” Carty says. “Some of it is about ‘collectors’ of all kinds – anthropologists, trophy hunters, police, missionaries. People who were on the frontiers of developing colonial Australia were often curious about Aboriginal people, and they would use the bones of Aboriginal people as evidence of their difference. And often those remains would be sent to the Museum.”

Such attitudes reflect the spirit in which most western museums were established, a colonial paradigm that has taken decades to shift. “Museums began as places where people catalogued other cultures; you see that in our Pacific Cultures Gallery upstairs,” Carty says. “It’s part of that Enlightenment taxonomies of Europe, of seeing civilizations progress. And when you do that to living cultures, as we have done in Australia, there’s a real risk that museums hold people in the past.”

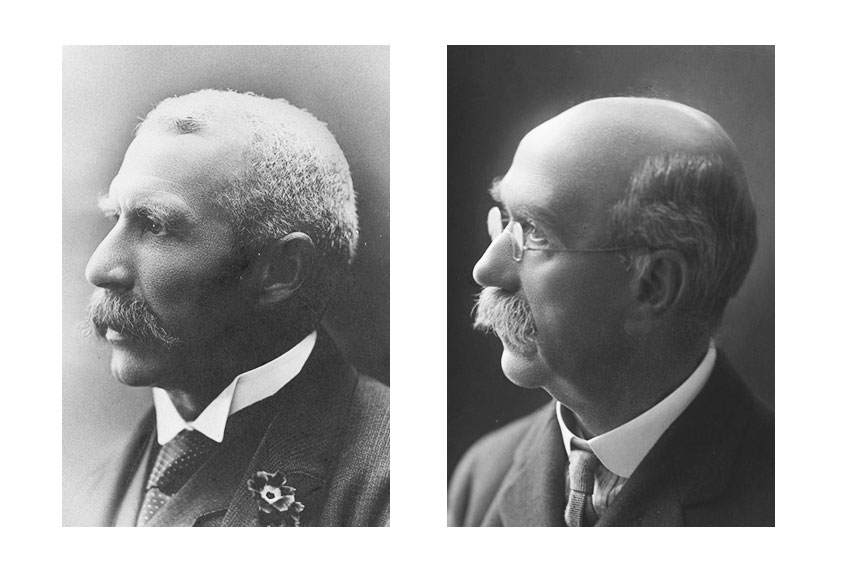

South Australia certainly casts a long shadow in this respect – many of the ancestral remains now being returned from overseas institutions were ‘collected’ by men like former Museum Director Edward C Stirling, University of Adelaide Professor Archibald Watson and physician and city coroner William Ramsay Smith. Most egregiously, Smith also trafficked remains stolen from burial grounds at Hindmarsh Island.

“The legacy of people like [Smith] is one that this museum, the universities, the whole town of Adelaide has to reckon with,” Carty says, “because it was people in the medical fraternity, the morgues… it was a systemic process of wherever Aboriginal graves were disturbed, rather than that being a reason to stop a development, the remains from those processes end up going to the Museum.”

It’s an important point: the transgressions of men like Smith are shocking today, but account for a relatively small proportion of the 4600. Many more were disturbed by land clearing, civil and private construction projects or members of the public – a confronting consequence of modern South Australia that many don’t realise exists. After all, there are few more powerful, tangible reminders of the scale of the colonial project’s dispossession of First Nations, and its overwriting of one culture with another, than the wholesale disturbance and removal of generations of buried ancestors.

“It’s kind of the story of building this town; this is a story that everyone who lives in Adelaide is complicit in, if not in the creation of it but the resolution of it, and the reconciliation that needs to come from reburying people,” Carty says. “Which is the work that we have to embark on now.”

In August 2018 at Tennyson Dunes, Newchurch (alongside a contingent of Kaurna, Ngarrindjeri and Narungga representatives) led the reburial of two Kaurna Old People returned from Sweden. Watched and supported by a diverse crowd of stakeholders and community members, the reburial demonstrated how culturally and logistically complex the work is. To return these 4600 will require coordination and real investment from state, federal and local governments as well as the community.

“From my perspective it’s a simple process: we do it together,” Newchurch says. “We worked with local council, community groups and government agencies and we did it together. Because if you do it together, then you start healing. You can only heal together.”

The act of reburial also poses cultural challenges, and is a significant emotional, physical and spiritual labour that First Nations peoples never asked for. “Culturally we’ve got to work this out, because we believe when they’re buried, they shouldn’t be disturbed,” Newchurch explains. “Unfortunately, mechanisms are beyond our control. So how do we adapt to that, and be innovative in this process of returning to Country?”

Moving forward, the Museum will work to better resource and support Aboriginal communities in leading the decision-making process. “It’s about inviting them to immerse themselves in what’s here, to take what they need and then go back to community, talk about it, and let us know what they want to do,” says the Museum’s Aboriginal heritage and repatriation manager Anna Russo, whose role was created in 2018 as part of a wider Museum restructure to make repatriation and Aboriginal agency a priority.

“That’s a big shift in the way repatriation has been managed at this museum in the past,” she says. The state government is also in the process of recruiting a dedicated Repatriation Officer to map out the resources required to implement a program of repatriation.

But for Newchurch, a change in policy is just the first step. It will take time, investment and hard work to ensure this document is more than a piece of paper. “We welcome the policy, but what is the content? Where is that substance of delivery? From an Aboriginal perspective, we are not resourced, we certainly haven’t got the mechanisms to do repatriation.

“You have the intent there. We want to work with the museums around telling those stories around those old people. The analysis is most critical; we need to know that story, our future generations need to know that story, and then in that story comes a better understanding, a better acknowledgement. And the process of healing begins.”

This article has been updated

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.