Royce Kurmelovs

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).

A gin-distilling data scientist pulls up a stool at the bar to talk blockchain, Facebook’s empire of data and the importance of vaccination.

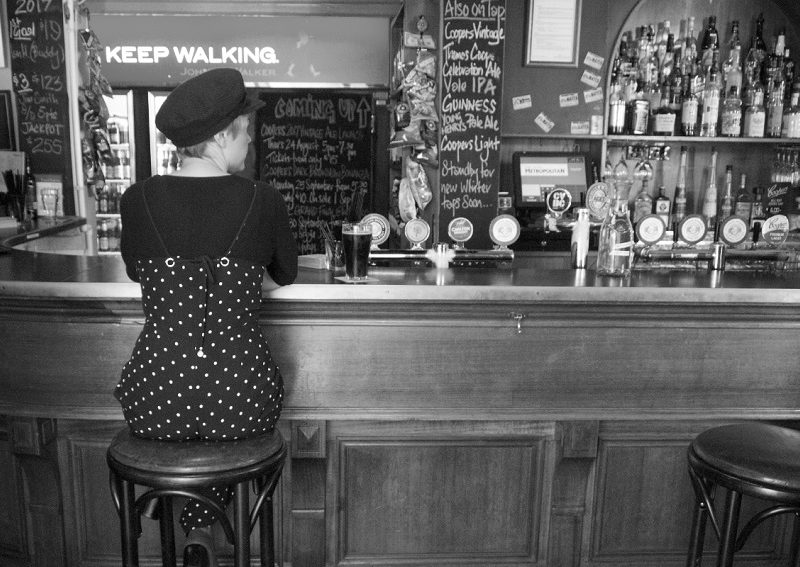

The bar down the road where Stuart Edwards is supposed to be isn’t open. The gates are locked and, while there are people inside, it looks like they’re staying that way. Still, it’s after work on a Thursday evening, so Edwards falls back for a beer inside the West Oak Hotel. There’s a chill in the wind as autumn falls and Edwards prefers to sit inside. Today, the place is a brightly-lit student bar, but once the West Oak was the Worldsend Hotel, a dingy little dive-bar on Adelaide’s western edge.

Before that it probably had another name, too. That’s how it goes. A thing gets made, then one day someone comes along and reimagines it into something else. Out of the old comes the new.

Edwards looks out of place in his neat office attire as he waits at the bar to order a pint. He takes his glass over to a table on which he places a bottle of his Sinkhole Gin. He explains it was something of a side-hustle. Some friends had the idea to use the water from a sinkhole on their property on the Limestone Coast and distil it into a liquor. With help from a Kickstarter campaign, they made it happen.

His regular nine-to-five is data science. Born in 1975, Edwards has been in the business long enough now that he remembers when it was once called “data analytics”. That was an old WWII term for the practice of using statistical techniques to peer into vast spreadsheets of data to see patterns and relationships where no one else had.

It was something that had made a kind of intuitive sense to him since the day his father brought home a Texas Instruments T1 99/4A computer so he and his older brother could play games.

Today, computer processors are small enough to fit inside a phone and most laptops come with a terabyte of memory as standard. Long before anyone imagined Skyrim or Age of Empires or The Sims or Sonic, the T1 99/4A was released with 16 kilobytes of memory in 1981 and there was no monitor. The whole system was built into the keyboard and the games it ran were loaded onto cartridges. Playing them meant connecting the thing up to a television.

When he grew up, Edwards went to Cambridge where he drank a lot of beer and studied the machines. When he graduated, he went to work for British Airways where his job was to investigate its travel booking data.

Over time his profession changed. Data analytics became data science and the world around it changed, too. Knowledge might be power but as soon as companies worked out knowledge is also profit, there came a certain faith in technology.

Sometimes that faith has descended into fanaticism. Edwards was in London for the dot-com era when companies like eToys.com floated on the share market, making everyone involved rich (at least until the crash in 2001). The collapse seemed to flush the city out.

There are still echoes of that mania around, Edwards says. There’s the blockchain obsession, the way that companies that own internet infrastructure act like cartels, and then there’s Facebook, which has more data about you than the combined forces of the FBI and ASIO.

That’s big stuff, though. The issues. Since Edwards moved to Australia to be with his wife, he’s mostly been focussed on the little things.

Just before Christmas 2017, Edwards and his wife bundled their little girl into a car and headed south out of Brisbane. Five days after Christmas, they turned up in Adelaide and noticed their daughter was looking grey. The GP had no idea what was wrong, but when they took her to the hospital the doctors quickly realised she had leukaemia. It was New Year’s Eve. She had just turned three.

Edwards says it’s been hard, but his daughter’s been through the worst of it now and is doing well. Today, she has a younger sister and a 90 per cent chance of survival .

“It means you can’t put her in day care and it has really messed up her vaccinations. She can’t have them right now,” Edwards says, gently. “It’s why people should vaccinate their kids. To protect those like mine who can’t.”

Edwards takes a sip of his beer. For now, he is mostly hopeful. He has his girls and a wife. He has his work. He now makes gin, which brings him joy.

He swirls the last mouthful of beer around in his glass before he asks if I want another round. I don’t, I say and he says he probably shouldn’t either. He downs the last bit of liquid and says goodbye.

Outside, we shake hands before he crosses the street and disappears into the night.

Royce Kurmelovs is an Australian freelance journalist and author of The Death of Holden (2016), Rogue Nation (2017) and Boom and Bust (2018).