There's too much in life: a tribute to Les Murray

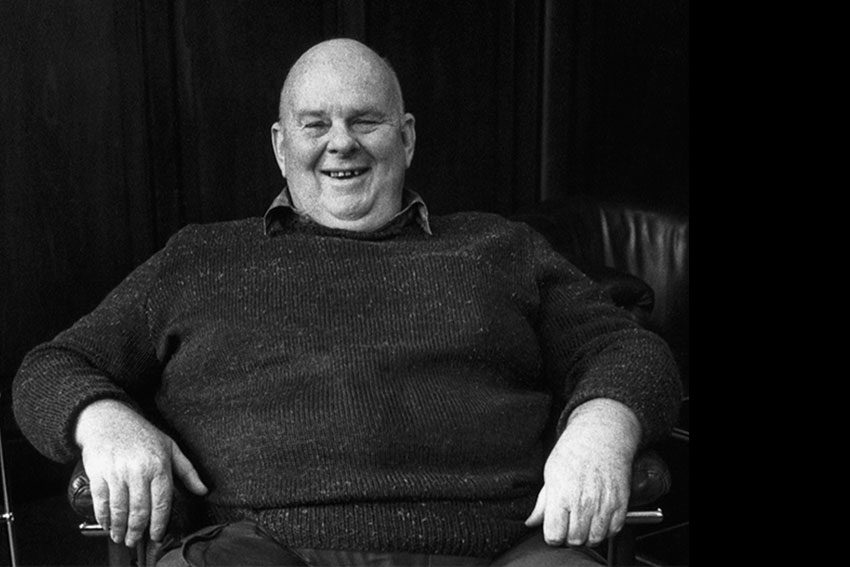

Luke Stegemann pays tribute to the late, great Australian poet, essayist and critic Leslie Allan Murray, 1938-2019.

Only the smallest children / and such as look out of Paradise come near him

– An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow

A memory has stayed with me, vivid over the years. At high school in Canberra in 1980, our senior English class was visited by a strange and shambling figure in an old blue cardigan; it was Les Murray, there to read some of his striking early poems, including Driving Through Sawmill Towns and the universally-loved, much-anthologised An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow. We were unware of just how lucky we were to have any writer – never mind a poet of this stature – read to us the very works we were studying in class. It was typical of the man, for Les Murray – capacious and talkative, but never frivolous – displayed the generosity that often characterises the truly great, the natural generosity of those who are deeply humble before the dimensions of the world.

The final line of Fredy Neptune, his epic novel in verse, runs simply: “But there’s too much in life: you can’t describe it.” It is a quiet conclusion to a vast, complex and wandering work, unlike anything in Australian literature. Yet ‘describe it’ Murray certainly could, and did. Unlike his protagonist Fred Boettcher – the German-Australian seaman rendered incapable of feeling after witnessing the horrors of the Armenian genocide – Les Murray felt and sensed, acutely, and spent his life wrestling common words, rare visions and unsuspected verbal formulations into the shape of essays and verse.

Murray’s work as a translator when a young man, to say nothing of his natural polylingual gifts, meant he brought a prodigious and musical originality to the task of creating a language sufficient to render the natural environment around him – principally Bunyah and the Taree district on the New South Wales central coast and hinterland. His was a miraculous conjuring act, adapting English, with all its historical northern inflections, to an Australian universe, painting our landscape, flora, fauna and social history in a dazzling vernacular that allowed Australians to see their country anew. Or in some cases, to see it for the first time.

Murray’s was not only poetry of the natural world, though that was arguably his finest achievement. His work – often humorous, often larrikin – also ranged over questions of family (the tragedies in his family tree were always present), cultural politics, the textures of rural life, depression, language, and the eternal question of how Europeans make sense of, and engage with, an Indigenous universe. Inevitably, in a country whose literary world is plagued with cliques and jealousies, Murray attracted detractors. Some could not understand – or better, could not forgive – his Catholicism; others, his socially conservative politics. That some found in these reasons to dismiss his work suggests a limiting intellectual and cultural environment.

For Murray understood tyranny: not that imposed by gaudy dictators, but by the demands of cultural and political orthodoxy. Such freedom always comes at a cost, and many never forgave Murray his independence of thought and disdain of cultural conventions. In defiance of all literary fashion he continued to dedicate his books “to the glory of God” for Les Murray knew there were forces within and beyond, there was lightning and there was darkness, far greater than our own temporal selves. He knew he possessed a rare gift, but was never vain enough to claim it as ‘his own’, or consider it a personal virtue.

To take just one example of his unrivalled capacity for lyrical invention and dexterity: in Lyrebird, from Translations from the Natural World (1992) he embodies the lyrebird, with its ability to mimic any sound, and creates – in this as in all the poems of the series – an aural masterpiece where words are sounds lifting us beyond human perception:

Tailed mimic aeon-sent to intrigue the next recorder,

I mew catbird, I saw cross-cut, I howl she-dingo, I kink

forest hush distinct with bellbirds, warble magpie garble, link

cattlebell with kettle-boil; I rank ducks’ cranky presidium

or simulate a triller like a rill mirrored lyrical to a rim.

Such verses, while brilliant on the page, burst into life when spoken aloud. These were no mere idle musings; as Murray explained in Killing the Black Dog (1997), his account of a lifelong struggle against depression, he was trying to get away from himself into something other, something less painful: “I gave my stupid self a rest and tried to enter imaginatively into the life of non-human creatures and somehow translate that life into human speech.” His embodiment of bats (Bats’ Ultrasound) and cows (The Cows on Killing Day), two animals he loved greatly, are now legendary moments in Australian poetry.

It is also worth noting, and we can say proudly, that over the years his poetry regularly found a home in The Adelaide Review.

Les Murray’s life and work is inconceivable without the unwavering love and support of his wife Valerie and his five children, all of whom survive him. “Everything except language / knows the meaning of existence” he famously wrote. Rest in peace.

Luke Stegemann is the author of The Beautiful Obscure and is a former editor of The Adelaide Review