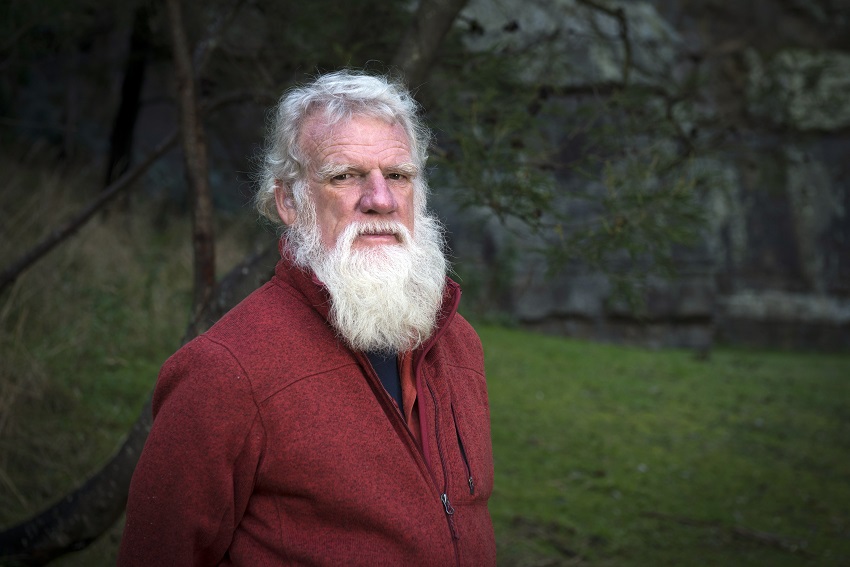

Walter Marsh

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.

With his bestselling book Dark Emu, Bruce Pascoe delves into Australia’s historical record to reveal a vision of First Nations societies vastly different to that typically shown in school textbooks. Now, a new edition for younger readers seeks to help a new generation of Australians see the country beyond the blinkers of colonialism.

“I wasn’t taught at all,” Pascoe tells The Adelaide Review of his own experience of Aboriginal history in school. “It was all explorers and wool – I can remember on King Island colouring in a boomerang. That was it.”

As Pascoe grew older and explored his own Bunarong, Tasmanian and Yuin heritage, he was confronted by just how little he knew. “When I started working on the research for Dark Emu, I was being surprised every day by my own ignorance, and how incurious I had been about the history. I was very uneasy about the history because it just didn’t make sense; I’d been too accepting of what I’d been taught.”

The resulting text revisits the original accounts of the first waves of colonists like John Batman, James Kirby and onetime South Australian governor Sir George Grey, as they variously encountered miles upon miles of cultivated native crops, carefully maintained dam systems and fish traps, and built settlements that could house hundreds. These entries plainly describe things that their own writers could not or would not recognise: complex societies with sophisticated agricultural practices, infrastructure and governance.

“It was very shocking, to be aware of how complete the obfuscation of the history had been,” he says of these encounters, and their relegation to obscurity. “I think that mentality was essential to colonialism. When people moved out of Europe, in our case England, they were doing so with that colonial viewpoint: we are the masters of the world, the rest of the world is a basket case and we’re here to fix it all up. But it was really a kind of intellectual blindness that the British could deceive themselves and the rest of us so much. Kirby’s words are indicative of the fact that British people came out here determined not to see Aboriginal people as human.”

It’s a simple but powerful feat of historiography that reveals a stunning alternate view of pre-colonisation Australia, one long ignored in favour of the more simplistic and politically convenient narrative of the hunter-gatherer. Pascoe recalls meeting with a group of Canberra university professors early in his research for Dark Emu who were concerned by his ‘reckless’ critique of the hunter-gatherer consensus.

“I realised then if I couldn’t convince the most intelligent people in Australia, then I had no hope of convincing people whose job history wasn’t,” he says. “The ordinary Australian who goes about their lives, how can they be expected to understand or accept this new explanation of history? I wasn’t rewriting history, the history was written by other people, it was written by the explorers and the so-called ‘pioneers’. So there was no ‘rewriting’ going on, just lifting away the veil.”

It’s an encounter that informed much of Dark Emu’s creation, both in its choice of sources (how better to convince historians than on their own preferred battleground of the written primary document) and its tone. Dark Emu does not shame its readers for their ignorance, born as it is from generations of incomplete teaching and a pre-colonisation landscape utterly transformed by the teeth and feet of sheep and cattle – not to mention their owners. “You know the erasure of those [stories] is a really important part of the history of the country,” Pascoe says, “because that helped successive generations to forget all about it.”

Since its publication in 2014, Dark Emu has proved a sleeper hit, in a near-continuous state of reprinting with over 100,000 copies sold, numerous literary awards won and a contemporary dance adaptation that premiered at the Sydney Opera House in 2018. “It was always my intention to have a young version, even before the publication of the original,” he says. “Once I realised how hungry Australians were for this information, and I began talking to people around the country, a lot of people were saying ‘Well, what are we going to teach our kids?’”

“The teachers’ notes in the book itself are at pains to get kids to question everything,” Pascoe says of Young Dark Emu, finally published in June after years of working with experts to adapt the book into an illustrated 80-pager tailored to modern curriculums. “If you find this surprising, well, go back to the sources and ask other people, start a debate. I don’t want people just saying ‘Oh yeah, we’ve changed our mind and these are the facts’. Examine the facts, because behind the facts there’s a whole new appreciation of how to treat Australia. And we’re going to need it – we need our young people to be active in the change because we’re destroying our country, and we need to fix it.”

Like the original, Young Dark Emu offers not just a history lesson, but a road map for how we might harness native species and First Nations land practices to live sustainably in an ecosystem dramatically reshaped, first by two centuries of colonisation and now by climate change. “It’s not about being a ‘bleeding heart lefty’ or anything like that, it’s cold hard economics: if we destroy our soil we’ll destroy ourselves,” he says. “[Kids see] this is a story that makes sense, they can see where it links up, they can think of country they’ve seen themselves. So the kids aren’t surprised, they just get excited. Because this is their country, they’re learning about their country.”

As Australia wrestles with rivers of dead fish, soils plagued by salinity and erosion, and constant water scarcity, it is clear that after just two centuries the relationship with the land set out by those first colonists bears fundamental flaws. How better to restore it than by looking to the world’s oldest living culture, who thrived for millennia?

“The settlers felt like they were at war with the country,” Pascoe says. “We need to be at peace with the country.”

Young Dark Emu is out now through Magabala Books

Update: Bruce Pascoe will appear at Adelaide Writers’ Week 2020

Walter is a writer and editor living on Kaurna Country.