Don, but not forgotten

As the state’s great progressive hero of the 20th century, Don Dunstan remains an influential and polarising presence in South Australian politics and culture. Two decades after his death, a new biography offers a comprehensive account of the former Premier’s life and legacy.

“I came of age when he was Premier, and as a young person in the late 1960s and 70s it was so clear that the world was changing, politics was changing, and it was apparent that Don Dunstan was a major force in all of that change,” author Angela Woollacott tells The Adelaide Review.

“What I wanted to do was show the significance of his family background, his childhood, but also to trace his education, his intellectual development, political thinking and how it evolved. I really set out to cover his entire life in multiple facets, and to take the intellectual and the political very seriously, as well as the personal life.”

No small volume of ink has already been dedicated to Dunstan’s life and achievements, from reams of contemporary media coverage to his own 1981 political memoir Felicia – Dunstan even spent his final years as an essayist in these very pages. But while Dino Hodge’s illuminating 2015 book Don Dunstan: Intimacy and Liberty viewed Dunstan’s political career through the prism of his sexuality – and offered a striking de facto history of Adelaide queer culture along the way – Woollacott’s book, simply titled Don Dunstan, marks the first comprehensive published account of his life and career.

“So much about Dunstan has focussed on his personal life,” she says of Dunstan’s queer identity and the complex relationships with women and men which have so often enthralled his supporters and detractors alike. “That’s very important and for a biography it’s crucial – you can’t do a biography without the personal life in there – but my feeling had been that some other things written about him just hadn’t looked at the intellectual and political side as seriously as I wanted to.”

To piece together Dunstan’s full story Woollacott, who is also the Manning Clark Professor of History at the Australian National University, spent years delving into the archives of the Flinders University Dunstan Collection which houses his own personal papers alongside a trove of oral histories from those who knew him. One of the more intriguing sources is Dunstan’s unpublished mid-80s novel The Education of Roger Kenwright, a bildungsroman whose hero is a thinly fictionalised stand-in for Dunstan himself.

“I didn’t know about it before I started the project, and when I came across it in the archives I was blown away,” she says of the manuscript, which was likely written during his short stint in Melbourne as Victoria’s Director of Tourism. “He tried really hard to get it published, he had an agent and they tried about 20 different publishers.

“There is an anonymous reader’s report archived along with the manuscript that makes it clear that the reviewer thought that it just didn’t work as fiction, and he should have written it as autobiography. But for me it was this amazing find, because I had to keep reading through to figure out which bits are fictionalised, and what can I really use.” In interviewing many of Dunstan’s schoolfriends for the book Woollacott was able to corroborate key passages that helped her separate ‘Roger’ from Don. “For me it was a really helpful tool to understand aspects of his growing up, his life in Fiji and his family.”

It was Fiji’s racial diversity and colonial hangovers, Woollacott argues, that would influence much of Dunstan’s politics later in life as he campaigned for constitutional reform, an end to the White Australia policy, and Aboriginal land rights. “One of the things that was so important about his story was that he was so passionate and so committed and principled on a number of things, especially racial equality, and I try to show that it was growing up in Fiji in that very stratified, unequal system that made it such a point of passion for him.”

Dunstan’s decade in government is often remembered for its radical social reforms and flashy cultural transformations, but Woollacott takes care to point out that Dunstan also knew the value of playing the long game. Labor in South Australia had already spent two decades in opposition when Dunstan was elected as the member for Norwood in 1953, and over the next 12 years he was instrumental in the decade-long effort to unpick the Playford government’s gerrymandered grip on power.

“I hadn’t appreciated just how hard and long he had to work to combat the gerrymander before he could do anything in achieving his political goals and reforms,” she says. “He had a significant role in the Labor Party from 1953 onwards in figuring out a strategy to work against the gerrymander, and to build up seat by seat by seat to the point that they were competitive, and then embarrass the Liberal party because they had so many more votes than the Liberals.” Woollacott found that Dunstan also worked to transform the culture of the party itself on issues like the White Australia policy – the ultimate example of the ‘change from within’ touted by modern Labor progressives.

Once in power Dunstan worked at a relentless pace across social, economic and cultural policy, while also maintaining a busy schedule of extra-curricular activities that placed him at the crest of a wider cultural shift in 1970s Australia. Even Dunstan’s quirkier contributions to popular culture are shown to have served a political purpose, such as the famous Don Dunstan’s Cookbook, which helped Dunstan boost Labor’s standing with female voters while also exposing readers to a variety of Asian and Mediterranean cuisines that reflected the period’s embrace of multiculturalism.

“Politically, socially and perhaps culturally, he was such a striking figure in his jewellery and his clothing, and caring about his hair – all of which for mid-to-latter 20th century Australian culture was unusual for a man,” she says of the pot-stirring, poetry-reciting Premier. “It really was a new form of masculinity which I think some people found hard to grapple with.”

Today Dunstan remains a polarising figure, and for some readers anything less than a scorched earth closet-airing will be written off as hagiography. But Woollacott does not ignore the more controversial periods of Dunstan’s career or his personal limitations, culminating in 1978 as political backlash to Dunstan’s dismissal of Police Commissioner Harold Salisbury dovetailed with rumours around his personal life and patronage, creating a storm of intrigue and innuendo that continues to fuel Dunstan’s detractors to this day.

But 20 years after his death, Woollacott contends that even his critics acknowledge and appreciate Dunstan’s impact on South Australia and the nation. “He was so divisive at the time and so many people love to hate him, but I actually think that some people who perhaps even now would not agree with him politically, have come to be proud of what he made South Australia.”

Don Dunstan (Allen & Unwin) is available now

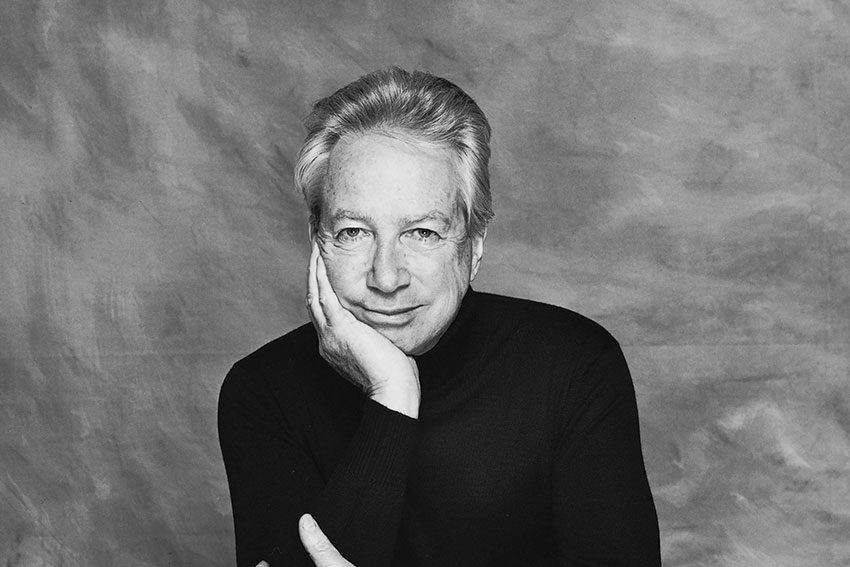

Header image:

Greg Barrett / National Library of Australia