The messages for next time from Labor’s 2019 election post-mortem are clear. Have a better strategy. Have a stronger narrative, fewer policies, greater emphasis on economic growth. Have a better leader.

Obvious. Incontestable. Just, as a package, devilishly hard to achieve.

The review by Labor elders Jay Weatherill and Craig Emerson identifies the plethora of reasons for Labor’s unanticipated failure. It doesn’t pull punches and contains sensible recommendations.

But no prescribed remedies can guarantee success, in a game where how the other side operates is as important – and can be more so – than what your side does. And that’s apart from the general climate of the times, these days characterised by uncertainty and distrust.

Political success comes from judgement and planning, but there’s also the lottery element. We’ll never know whether Bill Shorten could have beaten Malcolm Turnbull if he’d still been the prime minister in May. Turnbull would say no. Many of the Liberals who ditched Turnbull would say yes. Everyone would agree with the review’s conclusion that Labor failed to adapt when it suddenly faced a new, tactically-astute Liberal PM.

The review’s release was much anticipated, as though it marks a watershed. It doesn’t. It’s sound, well and thoroughly prepared. But it was never going to say how policies should be recast. It leaves the hard work still to be done, and that will be painful and prolonged.

While there’s been much emphasis on Labor’s big taxing policies, the review stresses they were driven by the ALP opting for big spending.

It says “the size and complexity” of the ALP’s spending promises – more than $100 billion – “drove its tax policies and exposed Labor to a Coalition attack that fuelled anxieties among insecure, low-income couples in outer-urban and regional Australia that Labor would crash the economy and risk their jobs”.

Labor has long believed in both the policy desirability and the political attractiveness of large dollops of money for education and health in particular.

Beyond a certain point, however, the value of ever more dollars becomes questionable, on both policy and political grounds. Is the community, for example, getting the return it should for the funds put into schools over the past decade?

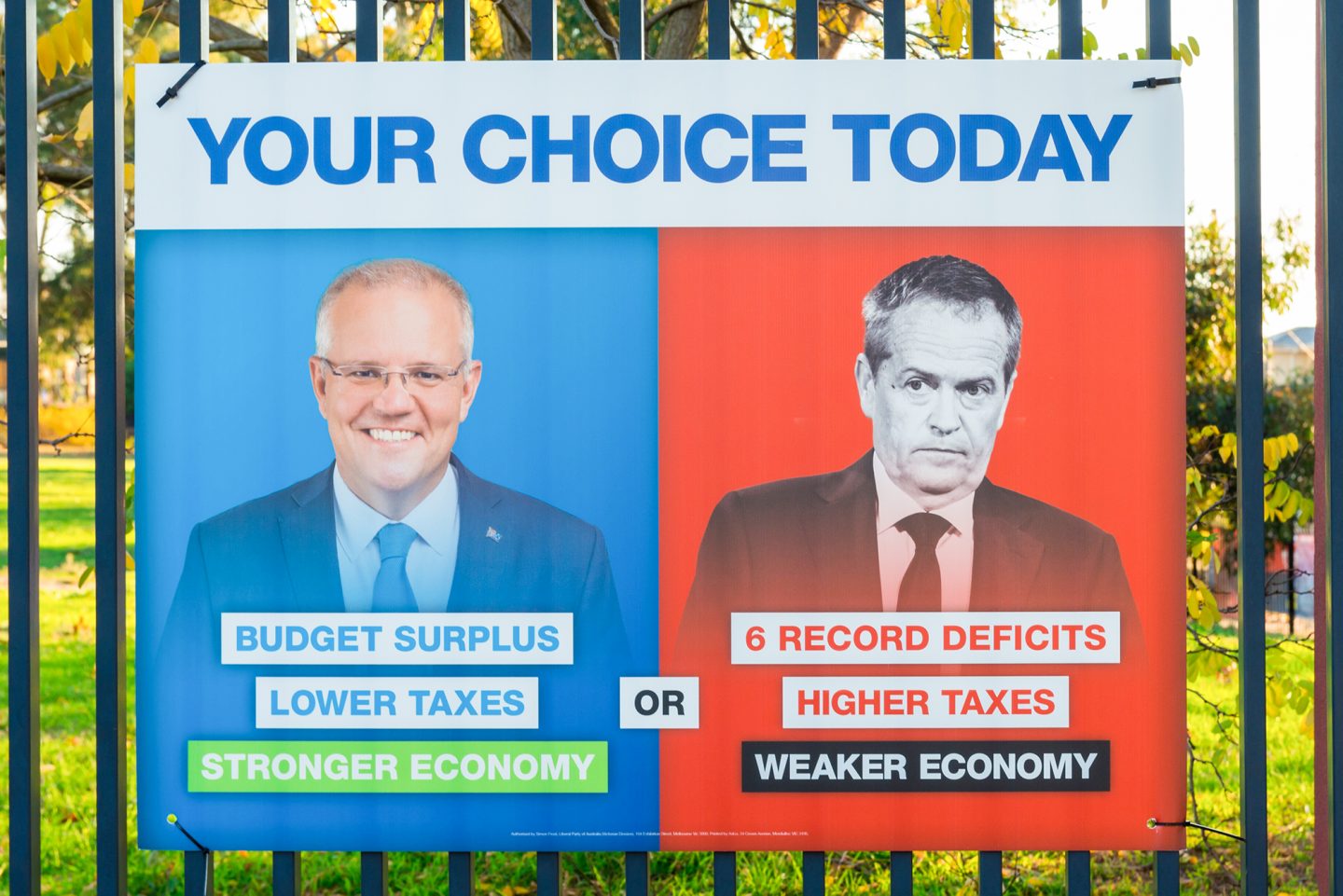

The Coalition’s election campaign tapped into uncertainties over the scale of Labor’s spending plans

The Coalition’s election campaign tapped into uncertainties over the scale of Labor’s spending plans

One can assume Labor will throw around fewer dollars next time.

The review doesn’t target the controversial policies on negative gearing and franking credits. But it is expected they’ll be watered down, at the least. The franking credits policy should have had a protection built in to avoid hitting genuinely low-income retirees while still catching wealthy people who’d rearranged their affairs to have little or no income. Shorten was advised to change it, but refused. On Thursday he said “were the universe to grant reruns” he would “take a different position on franking credits”.

However the internal debate goes, it will be a lot easier for Labor to deal with these tax measures than with climate policy.

The review says: “A modern Labor Party cannot neglect human-induced climate change. To do so would be environmentally irresponsible and a clear electoral liability. Labor needs to increase public awareness of the costs of inaction on climate change, respect the role of workers in fossil-fuel industries and support job opportunities in emissions-reducing industries while taking the pressure off electricity prices.”

Indeed. The summary just highlights the complexities for Labor in working out its revised climate policy.

Anthony Albanese has already put the policy, whatever its detail, into a framework of its potential for job creation as the energy mix moves to renewables.

It’s part of his broader emphasis on jobs and growth (accompanied by his pursuit of improved relations with business, never again to be labelled “the big end of town”).

It’s possible increasing public worry about climate change could help Labor at the next election, if the government’s response is seen as inadequate. That won’t, however, make it any less imperative for the ALP to have a better pitched policy than its 2019 election one, which was too ambitious, lacked costings, and was conflicted on coal.

This segues into Labor’s problem juggling its “progressive” supporters with its working class suburban base, to say nothing of those in coal areas. Taking one line in the south and another in the north didn’t work. The unpalatable truth may be these constituencies are actually not reconcilable, but Labor has to find more effective ways to deal with the clash.

Notably, the review points to the risk of Labor “becoming a grievance-based organisation”. “Working people experiencing economic dislocation caused by technological change will lose faith in Labor if they do not believe the party is responding to their needs, instead being preoccupied with issues not concerning them or that are actively against their interests,” it says.

This is an important warning in an era of identity politics. But again, Labor is in a difficult position, because its commitment to rights, non-discrimination and similar values will mean it attracts certain groups and has to be concerned with their problems. It’s a matter of balance, and not letting itself become hostage.

Grievance politics, looked at through a positive lens, is a way of identifying wrongs and injustices and seeking to rectify them. But it is also in part a reflection of the wider negativity infecting contemporary politics, amplified by today’s media.

That culture can add to the problems of a centre left party trying to sell an alternative.

Labor frontbencher Mark Butler recently noted that on the three post-war occasions when Labor won from opposition, it had immensely popular leaders (Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke and Kevin Rudd), visions for the nation and superior campaigns.

Whitlam sold a sweeping new program in tune with the changing times. Hawke promoted “reconciliation, recovery and reconstruction”. Rudd was welcomed as a fresh face embracing concern about climate change. Albanese has boldly dubbed a series of his speeches (the first already delivered) “vision statements”. But “vision” is an elusive elixir, apparently harder than ever to come by.

Winning from opposition is a struggle for Labor. This makes it crucial to have a leader who can both reassure and inspire swinging voters. Unfortunately out-of-the box leaders don’t come often; in reality, a party has to work with what it has got.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox

Get the latest from The Adelaide Review in your inbox