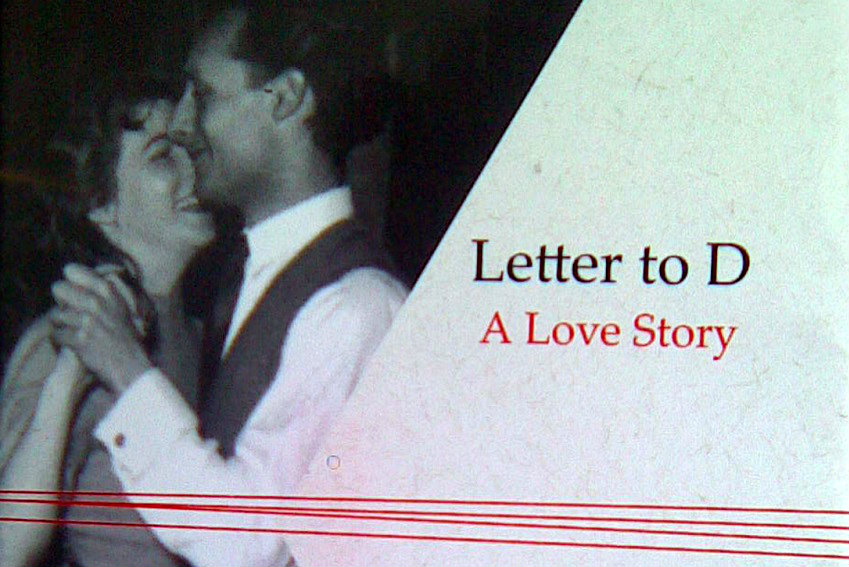

Modern Times: Reflections on Andre Gorz' Letter to D

When I got married, a dear friend gave me a most special gift: Letter to D, a novel but also a beacon; a reminder that there exists a possibility that cannot be realised through work, through politics or through sport. It is a possibility that is open to strong and weak, rich and poor; it is available to man and woman, man and man.

“I don’t stand a chance with her,” thought André Gorz when he met Dorine in October 1947. She was warned off Gorz – born Gerhardt Horz – by another man who described him as an “Austrian Jew. Totally devoid of interest”. Yet he did stand a chance and her interest he held throughout six decades.

Letter to D, published in 2006, is an open love letter. It was much talked about in Paris, the air of which their relationship breathed. Gorz, one of the more influential philosophers of the 20th century, opened his letter: “You’re 82 years old. You’ve shrunk six centimetres, you weigh only 45 kilos yet you’re still beautiful, graceful and desirable.”

Who, dear reader, does not want to feel the same devotion; who doesn’t want to bask in the same warmth? When he wrote these words, Dorine was in terminal decline, her body riddled with disease. The possibility open to all beings had been grasped and held with a conviction that squeezed tragedy from inevitability. Decline and end eludes no one.

But many, distracted by inexorable climbing, ignore the original possibility. The marriage of A to D was framed in a deeply intellectual context. She an actress and he a writer, both activists committed to socialism, but their relationship was founded on something other than reason. They were described by friends as “obsessionally concerned for one another”. Obsession expands reason, until reason is ultimately rendered irrelevant to the relationship.

My wife’s grandparents, Fred and Winnifred, were both swimming coaches. They still sit together every day on their porch, which overlooks the Swan River in which they once trained their swimmers. They built that house together from the foundation up, mixing the concrete to make each brick until it was finished in 1953. F and W then built Perth’s first 25-metre pool in their backyard, so that they could conduct their training sessions in conditions more suited to elite training. More than 60 years later, they too remain “obsessionally concerned for one another”; a concern untouched by old age and dementia.

Modern obsessions are seldom inspired by a concern for another. Motivated individuals today obsess over careers or bank balances. Others obsess about their favourite sporting team, whichever banality appears on their iPhones, or reality television which never fails to produce the spontaneity of two mirrors set against one another, reflecting into infinity.

Does modern life allow a person the freedom to enjoy an obsessive concern for another; a freedom, perhaps, from insecurity, from ego or from self-consciousness? Is such freedom a thing to which a person aspires today? These freedoms may appear antiquated, but Gorz showed that the pressure to be busy and temptation to be distracted is not unique to our generation, nor even to our century.

Gorz reflected that he had the impression of “not having lived my life, of always having observed it at a distance”. He wrote to D: “You were at one with your life; whereas I’d always been in a hurry to move on to the next task, as though life would only really begin later.” This recalls to me my two greatest fears. One, that I will sit next to S, my wife, when I am 80 and regret not having done enough with my life. The second that I will sit on the same porch and regret that I had tried to do too much, as though life would only really begin later.

For Gorz, it was a habit that he struggled to break but terminal illness is a disease that can focus the mind and, in their final years, they together decided to focus on the now. Earlier in Letter to D, Gorz had used a line by John Ruskin, that there was “no wealth but life”. The year after it was published, André and Dorine were found lying side-by-side in their home in Aube, north-eastern France, having taken their lives together. “Neither of us want to outlive the other”, he had written barely a year earlier. Their end was the product of a deep and unwavering commitment.

Gorz ended his Letter to D: “We’ve often said to ourselves that if, by some miracle, we were to have a second life, we’d like to spend it together.” Their story remains a beautiful gift to those of us who remain, scurrying around distracted, as though life will only begin later.