Modern Times:

Searching for the Great Australian Novel

American literature as long been fixated on the idea of the ‘Great American Novel’, but our own country has been somewhat reticent to embrace the idea of great, unifying texts.

The idea of the Great American Novel has been around for over 150 years. First coined in an essay by novelist John William De Forest, the Great American Novel is canonical reflection on American society in a particular era. Self-deprecating, lacking the national confidence of our Anglophone cousins, we in Australia do not discuss our literature in terms of its greatness. We should.

Patrick White is the only Australian to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He developed an identifiably Australian style which, according to author Christos Tsiolkas, was notable for its daring, its verve, and its harsh language. These characteristics are also evident in contemporary Australian novelists such as Richard Flanagan, Alexis Wright and Tsiolkas himself.

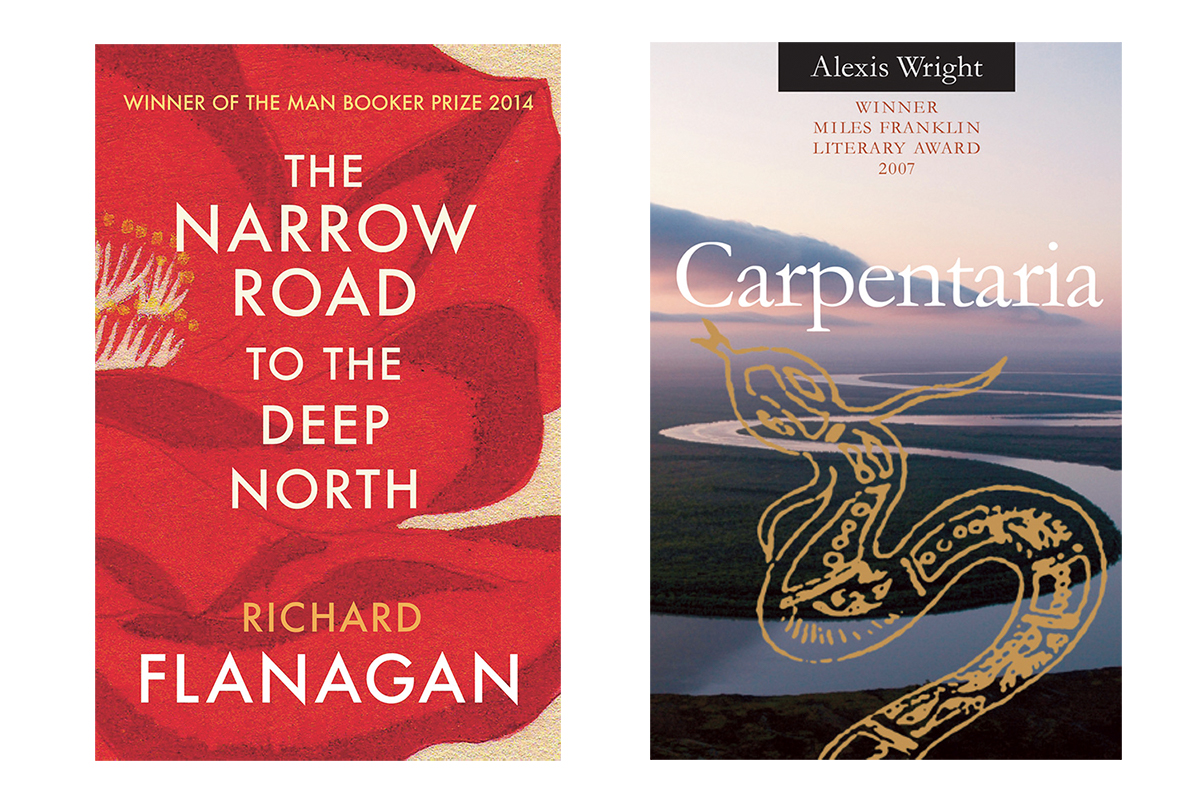

If asked to identify the Great Australian Novel that defines my generation, I reach for Carpentaria, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, and Barracuda. Each is an important reflection of this Australian moment. Each captures a different Australian experience. Each is written with a distinctive style. All are worthy candidates for the title Great Australian Novel.

Unlike contemporaries like Germaine Greer or Clive James, White did not feel the need to leave Australia to realise his potential as a great writer. He was perhaps the first significant Australian writer not to succumb to a cultural cringe, and his sureness was rewarded with a place in history. Does an enduring cultural cringe make it difficult for us to couple greatness with Australian literature?

Prominent contemporary Australian novelists do not feel the compulsion to build their reputations abroad. One cannot imagine Wright separated from her country, for any reason. Flanagan once studied at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar but writes from a Tasmanian abode. The cultural cringe no longer prompts our literary talents to leave their place of birth. But does it influence the way in which we see their relative talent?

Carpentaria is a meditation on race relations – a subject White dared not broach. It describes opposing perspectives with a raw poetry. It captures the wonder of Indigenous culture. It playfully teases the differing perspectives of black and white Australia. Occasionally, Carpentaria tries to merge these diverse perspectives and draw attention to those things that unite us:

This was the story about Elias Smith which was later put alongside the Dreamtime by the keepers of the Law to explain what happened once upon a time with those dry claypans sitting quietly out yonder there for anybody to look at, and wonder about what was happening to the world, and to be happy knowing at least this was paradise on earth and why would anyone want to live anywhere else.

In The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Flanagan captures a very different Australian experience: of war, and life after war, for those unlucky enough to survive. The unapologetic Australian attitude – to war, to love, to life – is not redolent of a writer suffering from cultural cringe. These once identifiably Australian attitudes, which have since been diluted by time and social change, capture both the quiet strength and smallness of Australia in the first half of the 20th century.

Would Barracuda be considered a Great Australian Novel? It does not lack in daring but, when compared to Carpentaria or The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which both deal with broader tragedies, there is an unmistakeable rage. Does this rage capture this Australian moment in a way that the other modern novels, though undeniably moving and beautiful, do not?

The greatest source of rage could be our national reluctance to esteem and aspire to greatness. We should start talking about the Great Australian Novel, or accept smallness as our destiny.