Peter Monteath

Peter Monteath is a Professor of History at Flinders University.

Iconoclasm – the destruction of images and monuments – tends to come in waves, and we are in the middle of a tsunami.

On 7 June indignant crowds in Bristol toppled the statue of 17th century slave trader Edward Colston and rolled it through the streets before consigning it to the depths of Bristol harbour. It was a fitting and long overdue end, many thought, for the image of a man who built his wealth on shipping African slaves.

On the other side of the Atlantic, too, statues have been beheaded or felled. In this part of the world the ire of iconoclasts has led to the daubing and disfigurement of monuments to individuals whose place in Australian history had long been uncontested.

Iconoclasm can be traced back to the ancient world. Its history underlines the potency and the sincerity of the passions it provokes. That history also offers an array of possibilities as to how communities and governments – not least here in Adelaide – might respond to iconoclasts’ demands in our own times.

In its earliest iterations the targets of iconoclasm were religious; rich veins of iconoclasm can be unearthed in all the major religions. While it might have achieved peaks of activity in the Middle Ages and the Reformation, religious iconoclasm remains with us. Think, for example, of the tragic, Taliban-sponsored destruction in 2001 of the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan.

More commonly in the modern world, iconoclasm is motivated by politics rather than religion. In the throes of its implosion, the entire Soviet bloc witnessed a wave of iconoclasm, as statues of Lenin and other heroes of the communist pantheon were torn from their plinths. The act of tying ropes or chains around the statues’ necks mimicked the executions of flesh and blood political figures over the centuries, whether by the sword, the guillotine or the noose.

Some escaped. The massive monument to Ernst Thälmann in the Berlin district of Prenzlauer Berg remains in place to this day, the city authorities contending with very divergent views on what fate should befall the image of the Communist leader, whose life was ended brutally in a Nazi concentration camp. It was above all the sheer size of the Thälmann monument that saved it from removal – and not everyone in the nearby apartment blocks regrets its unlikely survival.

Other relics of the Eastern bloc ended up in monument parks such as that outside Budapest, where icons of socialism convene in a kind of hushed recreation of a Comintern gathering. Called Memento Park, it houses the usual international suspects in marble and bronze – Marx, Engels, Lenin, Dimitrov – as well as local favourites, not least Béla Kun, who ruled Hungary for a few tumultuous months in 1919. Political figures dominate, but there is space too for preserving the standard tropes attached to the heroism of the unnamed: liberating soldiers, resisting workers and suffering martyrs.

Such figures dominate too, in Moscow’s Muzeon Park of Arts, formerly known as the Park of the Fallen Heroes. Like their counterparts in Hungary, these figures are doubly fallen. As living men and women, they gave their lives in the service of a great secular cause; as bronze/stone/marble recreations, they have been unceremoniously felled and then exposed to the tourist’s unsparing, ironic gaze.

It is ironic, too, that in our times the image of the act of iconoclasm often endures longer than the icon itself. Think of the statue of Saddam Hussain. Who outside of Iraq was familiar with the massive likeness of that country’s ruler on Baghdad’s Firdos Square? But who has not seen the still or moving images of the toppling of the statue, stage-managed to appear as an act of Iraqi regicide and self-liberation?

In Bamiyan, Berlin and Baghdad, the logic of iconoclasm has always been to symbolise regime change. The destruction of the old makes way for the installation of the new, and with it a new symbolic order.

What is unusual in the current wave of iconoclasm is that it does not seem to accompany the casting aside of an ancient regime, or perhaps just not yet. Rather, it appears as an expression of long pent-up failure to effect the kind of genuine progress that might render obsolete the clamour for radical change. Iconoclasm manifests as the assault of the voiceless on the mute.

Someone once quipped, we have monuments to remember, and memorials so that we don’t forget. Whether they reference the exemplary or the abhorrent, as catalysts in public spaces for genuine engagements with the past, monuments and memorials can indeed be hugely frustrating. Literally and metaphorically, they set the past in stone; their information load is pitifully poor. In their silence they express nothing but the most elementary of facts, ill-suited to grapple with pasts that are almost always more nuanced than they first seem.

Amid this current wave of iconoclasm, to what extent should we heed cries to repopulate our symbolic order? Or what steps might we take to rescue these flawed traces of the past from the condescension of the present? Communities, like individuals, cannot remember everything. Questions around who is worthy of remembrance and what must not be forgotten are legitimate subjects of debate.

Today, however, as in the past, the answers don’t need to be as stark as maintenance or destruction. In the German city of Bremen 30 years ago, locals pondered what to do with a 1932 monument to the fallen soldiers of Germany’s colonial wars. It took the form of a massive, red-brick elephant. The monument was transformed into an ‘anti-colonial’ memorial, its meaning cleverly inverted. The elephant remains on its pedestal, but with the help of a new plaque it remembers the “Victims of German Colonial Rule in Namibia 1884–1914”.

Closer to home, in a park in Fremantle, The Explorer’s Monument, erected in 1913, has undergone a similar transformation. It recalls three explorers who, as its original plaque puts it, were “attacked at night by treacherous natives”. and murdered near Le Grange Bay in 1864. A more recent plaque, added beneath the original as a corrective, contextualising addendum, explains, “This plaque was erected by people who found the monument before you offensive. The monument describes the events at Le Grange from one perspective only: the viewpoint of the white ‘settlers’.” It goes on to point out that a punitive expedition led to the deaths of some 20 Aboriginal people, but it also takes on the task of commemorating all other Aboriginal people killed in acts of frontier violence.

Here in Adelaide the ire of the iconoclasts has been directed primarily at William Light. To assault Light as a racist seems a little akin to toppling a monument to Florence Nightingale because she aided the prosecution of an imperialist war.

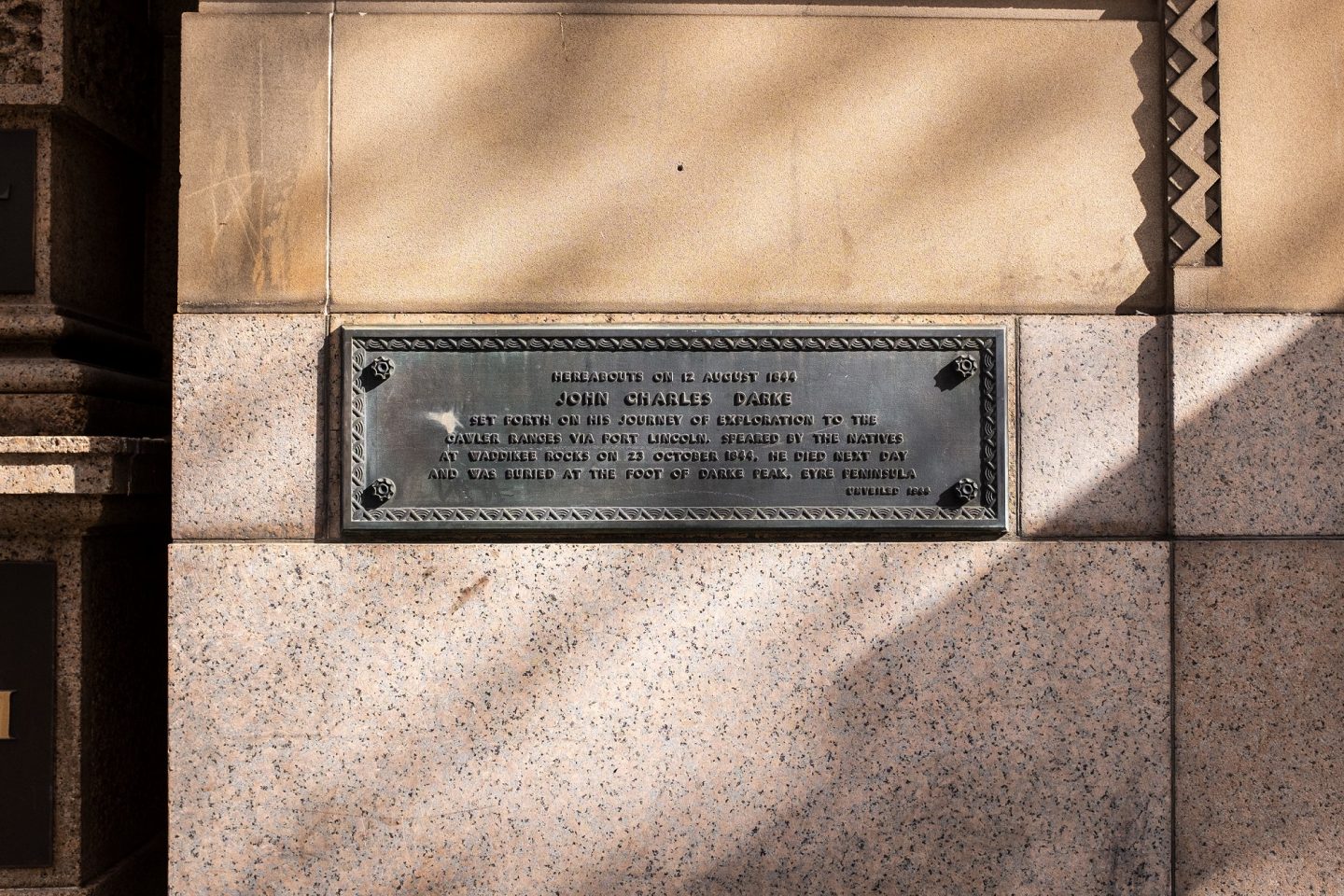

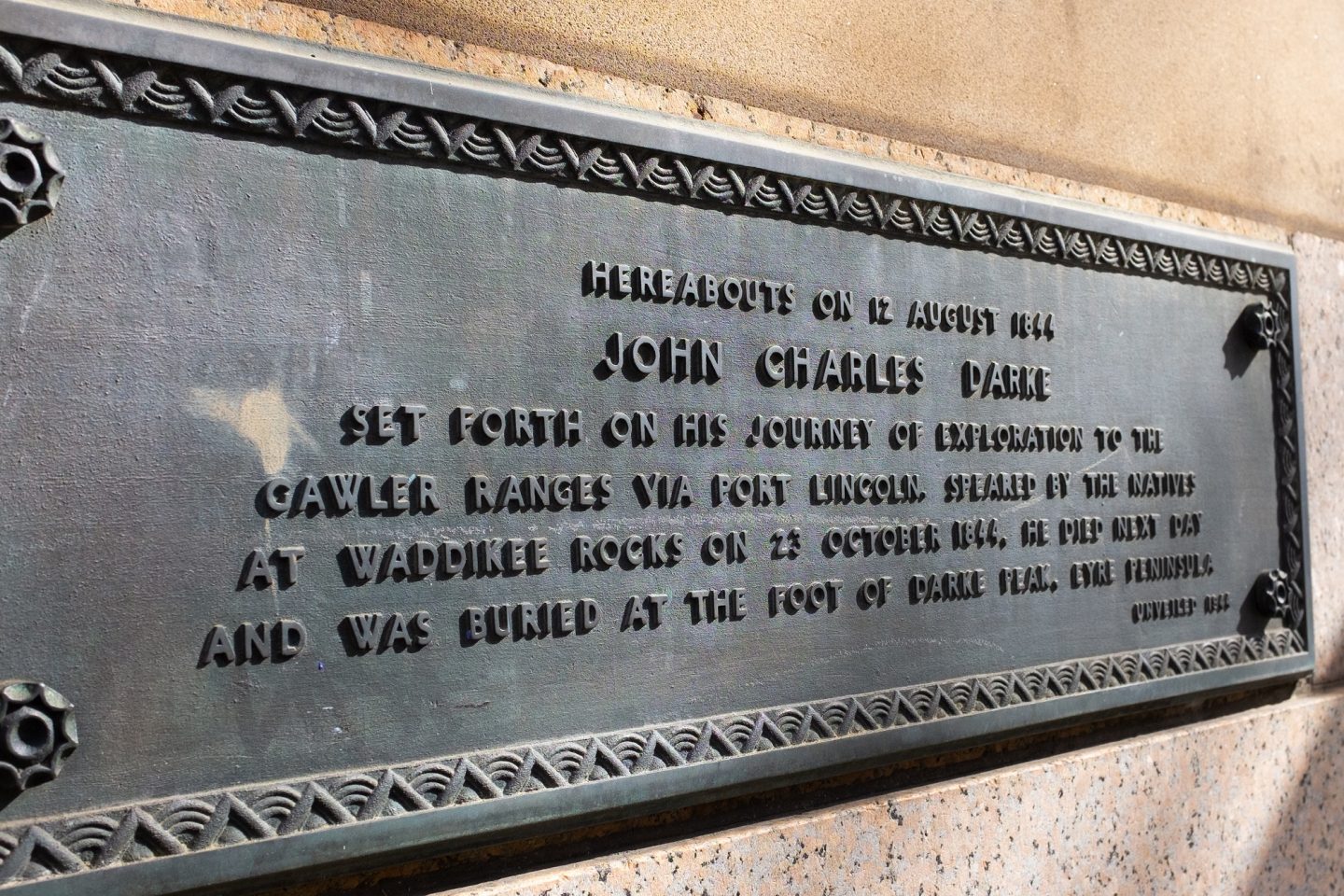

More troubling in my view than any Light icon is a plaque adorning a building on King William Street. Unveiled in 1944, it marks the starting point of an exploratory expedition to the Gawler Ranges, led by one John Charles Darke a full century earlier. Darke, the plaque tells us, was “speared by the natives at Waddikee Rocks on 23 October 1844. He died next day and was buried at the foot of Darke Peak, Eyre Peninsula’.

It was from similar locations in the heart of Adelaide that other expeditions commenced – including one led by Charles Sturt to Central Australia just a couple of days earlier than Darke’s. The cost of those expeditions and of the expanding European presence that followed was indisputably carried primarily by the country’s original owners, and not just in the amount of blood spilt and lives lost at that time. It’s a shame that this Darke tribute still stands alone.

Peter Monteath is a Professor of History at Flinders University.