Stephen Orr:

The dangerous country

In Blood Hunger (Sheena, Queen of the Jungle #1, 1942), socialite Irene Sprawling arrives in the dark continent and demands that Sheena (hand-tinted bouffant, tiger-skin swimsuit) supplies a guide for her expedition. Sheena refuses: “I’ll not send my people through dangerous country to suit your fancy!” The reason I mention this is twofold. Firstly, the way we learn (a kid with a comic, a magazine, a journal, The Adelaide Review) about the world; secondly, the importance of the people who guide us through it.

Morph to Marion Shopping Centre, earlier this year. A nine-year old boy following his family, caught up in a book. I think: I recognise you! Later, I see the boy on his knees in QBD trying out another book.

I began writing for The Adelaide Review (always the definite article) in 2008. I went to Adelaide Writers’ Week, saw the same big names, thought why? Went home, rushed off a piece about local stories, local writers, local readers, submitted it to Lachlan Colquhoun, then editor. It made its way to ABC Online, offended a few Burnside hausfraus, and I was off and running. Followed by a long story called An Unholy Communion, a thinly-disguised take on the Reverend Mountford incident. This ran over three editions. Severely-edited, truncated, four speakers stuffed on a line – but it was published.

The Adelaide Review was always a safe space for me, a place to hone my skills, rattle on about my preoccupations, gather a following (of sorts). During the next 10 years I wrote what I wanted, offended with reckless abandon, praised where necessary. I can only think of one piece refused publication (something I said about The Sunday Mail). I was lightly edited (or not at all), but felt the need to be as good as those beside whom I was published. I shared the stage (or blue pencil) with people I respected (Alan Brissenden, Graham Strahle, Luke Stegemann, Lachlan Colquhoun, David Knight and many more) and was always aware of the progenitors, especially Christopher Pearson. I was always well paid, always strayed wildly from my word count, but was rarely made to cut a word.

In short, The Adelaide Review was literary Nirvana (as I return to the Realm of Hungry Ghosts). As I published more fiction I had a handy outlet for extracts. I was leading my readers through (if not dangerous country) a landscape of ideas, possibilities. I wrote about Adelaide, its potential and its (frequent) failure to realise it. I discussed local tintypes, eccentrics, visionaries (from Gustav Hermann Baring to Barbara Hanrahan, Max Harris to Rose Grainger); posed questions, wrote about Adelaide’s smells, myths, history, lacklustre political leadership. I was allowed to write whatever (and however) I liked. In an age of metrics, of untested orthodoxies, I was afforded the joy of indulgence. Just like the boy in QBD, I was allowed to go off and explore. And by helping others along the path (always slashing at the vine), I worked out what it meant to be Adelaidean.

So what now? Are we condemned to an eternity of intercol football, mega-utes and shiny new petrol stations? Endless photo ops for the Suits? The unholy communion of politics and populist media. People need proper dreams, visions, alternatives, analysis (or Uncle George, always carrying a mirror in his pocket for self-reference).

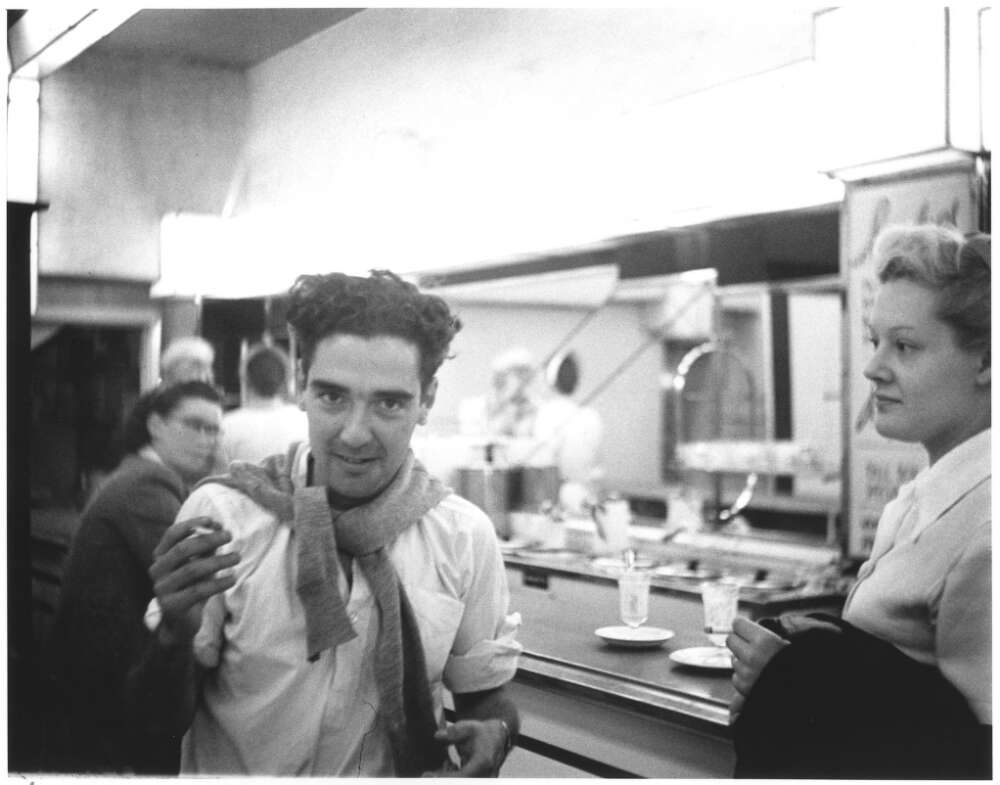

I wish I had longer to say more, but brevity, or silence, is the future. I’ll leave you with one image. I was nine or 10, went to see something at the Piccadilly on O’Connell Street, went to the toilet, washed my hands, looked up and saw Don Dunstan. I gave him that I-saw-you-on-the-telly look, and he smiled and exited. I knew there was something important about this man, but wasn’t sure what. Of course, now I know. He was someone who promised to make us better than we’d been. Someone to lead us through dangerous country, and emerge better on the other side.