A good plan to help Darling River fish recover exists

A decade of bipartisan research has provided plenty of answers to the problems plaguing the Darling River.

The recent catastrophic collapse of Darling River fish communities is truly heartbreaking. As fingers continue to be pointed in all directions, two questions bubble to the top of mind: can this system recover? And, if so, how?

From even the darkest hour comes hope. It was wonderful to hear the basin’s various governments speak about developing a “strategy” over recent weeks. And the good news is that one already exists and can guide our actions from here.

The Native Fish Strategy

The Native Fish Strategy for the Murray-Darling Basin is a living document. It was developed in 2001 and lays out a plan for helping the basin’s fish communities recover from where they are now, at 10% of pre-European levels (0% in some parts), back to 60% over 50 years.

The strategy is one of the rare documents agreed to by the federal government and all basin states: because it made sense. It was visionary and forward-thinking – contributed to by a multitude of scientists, managers, Indigenous groups and basin communities.

During the first ten years of its life the strategy helped us learn more about our native fish than in any other period. But direct funding ceased in 2012. Since then, implementation of its recommendations has been opportunistic and without central coordination. That said, the strategy is still relevant and the need to resurrect its funding has never been greater.

The Native Fish Strategy recognised that native fish are recreationally and culturally valued by all those who live in, and visit, the Murray-Darling Basin. It also acknowledged that most native fish species found there aren’t found anywhere else in the world.

Most importantly, the strategy describes these fish as important indicators of ecosystem health. That should be a warning to us when considering recent events in the Darling. When fish are stressed, it is because our rivers are stressed. It’s that simple.

How to help our fish

Our native fish are pretty simple creatures, really. They need healthy habitat, more natural water flows, the ability to move around, minimal pests to compete with, and sparing use of active human intervention (including stocking). The first decade of the strategy sought to provide hard data on how a range of different threats impact fish. It also successfully trialled a suite of solutions.

Because of the strategy, we know why aquatic and riparian habitats are crucial for fish. And putting habitat back in the river, through plans like building fish hotels (yes, they are a thing), can help fish recover rapidly. Many decades of clearing the Darling River of logs and minor obstructions has left large stretches smooth and unsuitable for fish to lay eggs, shelter or hide from predators, so reintroducing native plants and natural “snags” is essential for a productive future fishery.

The current drought, the second in ten years, has added to the need for better water flow regulation. Not to belabour the obvious, but fish need water. Some parts of the Darling main channel have been dry for some time. No water means no fish.

Many wetlands in the Lower Darling have not been watered for more than a decade. For some fish in the Murray-Darling, that is one-third of their life; for others it is longer than their lifetime. Native Fish Strategy research taught us that with the right amount of water, fish will spawn and thrive, but it is important that the water is of high quality, is flowing, and connects fish with their crucial habitat.

Finding the balance

Fish scientists and managers are realists and recognise that there will always be competing uses for water – including irrigation and town supply. But the fact that our fish stocks are so stressed highlights the need to find a balance.

Many people don’t realise that when water is taken for irrigation or drinking, fish are inevitably taken with it.

Work under the Native Fish Strategy demonstrated that anywhere between 100 and 12,000 fish can be abstracted, per day, by a single pump. When extrapolated over the many thousand irrigation pumps and diversion points across the basin, this means millions of fish are lost each year. They are either diverted into water distribution canals, or pumped onto crops and die.

This can be fixed by fitting pumps with off-the-shelf or custom-designed fish screens. Each pump that can be fitted with a screen in the Darling will translate to thousands of fish that will stay in the river. When conditions are right again, screening pumps will be a key to helping fish recover. Presently, no pumps on the Darling are fitted with screens for fish protection.

We also know the Darling River is an important fish swimway. There is a famous story among fish scientists of a tagged golden perch which, during 1974 flooding, migrated from Berri in South Australia to the Condamine River in Queensland. It is a stark demonstration that fish in the basin ignore political boundaries. But in non-flood years such a migration is impossible; there are far too many barriers such as weirs and dams.

There is strong evidence that in some years the Lower Darling contributes significantly to fish populations in Victoria and South Australia.

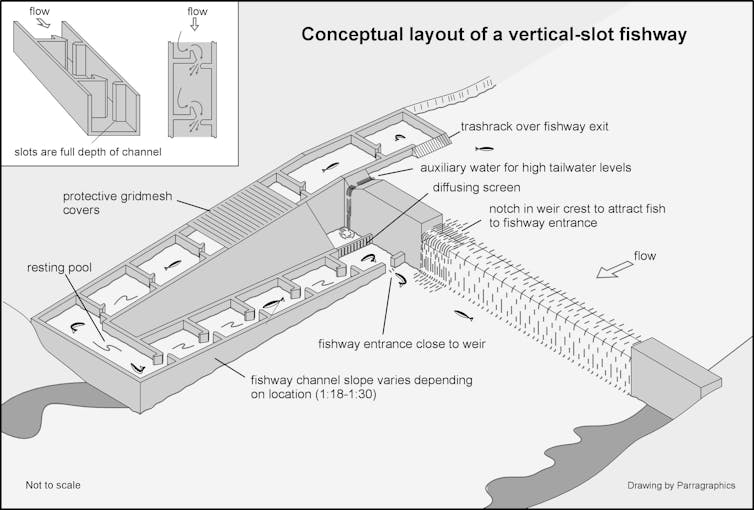

This connectivity is of paramount importance for affected reaches of the Darling. For these reaches to recover, fish need to migrate from elsewhere. The Native Fish Strategy taught us that providing fishways (also known as fish ladders) and fish-friendly regulators with layflat gates helps larvae drift downstream, improving recovery. There is already a blueprint available to connect the Darling: it only needs to be implemented.

What does the Darling’s future look like?

The Native Fish Strategy has provided us with a range of tools to help the Darling River quickly recover. So the future of the Darling depends on what we do now. It is up to us to ensure we leave future generations a river in better condition than it is in now.

This is our Waterloo moment. The scoping work has been done; the strategy already exists; the solutions have already been developed and tested. But all of this is meaningless if it’s not used. The Darling River has sent us a strong message. The question is: will we listen? We bloody well need to.![]()

Lee Baumgartner, Associate Research Professor (Fisheries and River Management), Institute for Land, Water, and Society, Charles Sturt University and Max Finlayson, Director, Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Header image:

Shutterstock